Journeying Through Cultures in The Art of Dying Well

In the 15th century, the 'Ars Moriendi' emerged as a vital companion for the living as they prepared for the final journey. This collection of Christian texts, crystallizing during the Council of Constance between 1414 and 1418, offered counsel on dying well in an age of plagues and spiritual uncertainties. Such guides were not exclusive to the Western world. Across the vast expanses—from the vibrant cultures of Africa to the storied civilizations of Asia and throughout Europe's varied lands—people have perennially sought to understand and articulate the transition from life to death. Let us traverse the annals of history to rediscover these venerable traditions that speak to a pearl of collective wisdom. In the contemplation of death, we unearth life's ultimate teachings to be embraced and honored.

Egypt

In the dunes of Egypt, the tales of Seth and Osiris' rivalry stand apart, not just as myth but as narratives that captivate like any storied fiction. Osiris, king of Egypt and the beacon of harmony, ruled justly, but the shadow of Seth's envy loomed perpetually, eager to usurp. The legendary feud sowed the seeds of Egyptian custom, particularly after Seth's moment of triumph.

At a grand feast, Seth presented a golden chest, promising glory to those who fit within. Osiris, enticed, met the challenge, only to find the chest a trap set by Seth. It was designed for only the king’s dimensions. Leading to his watery demise in the embrace of the Nile.

But his story did not end there. Isis, wife, and sister to Osiris, took the guise of a falcon and scoured the earth for her lost consort. She found and resurrected Osiris with magic and devotion, who then chose to preside over the afterlife, becoming its sovereign arbiter.

This narrative knitted itself into the fabric of pharaonic belief — the divine screenplay dictating that gods and their chosen would rise again. In death, as in this story, they prepared for resurrection, their hearts preserved, their bodies anointed and adorned, ready to step into Osiris's domain — an eternal field of reeds, where life's joyous labors continued unabated.

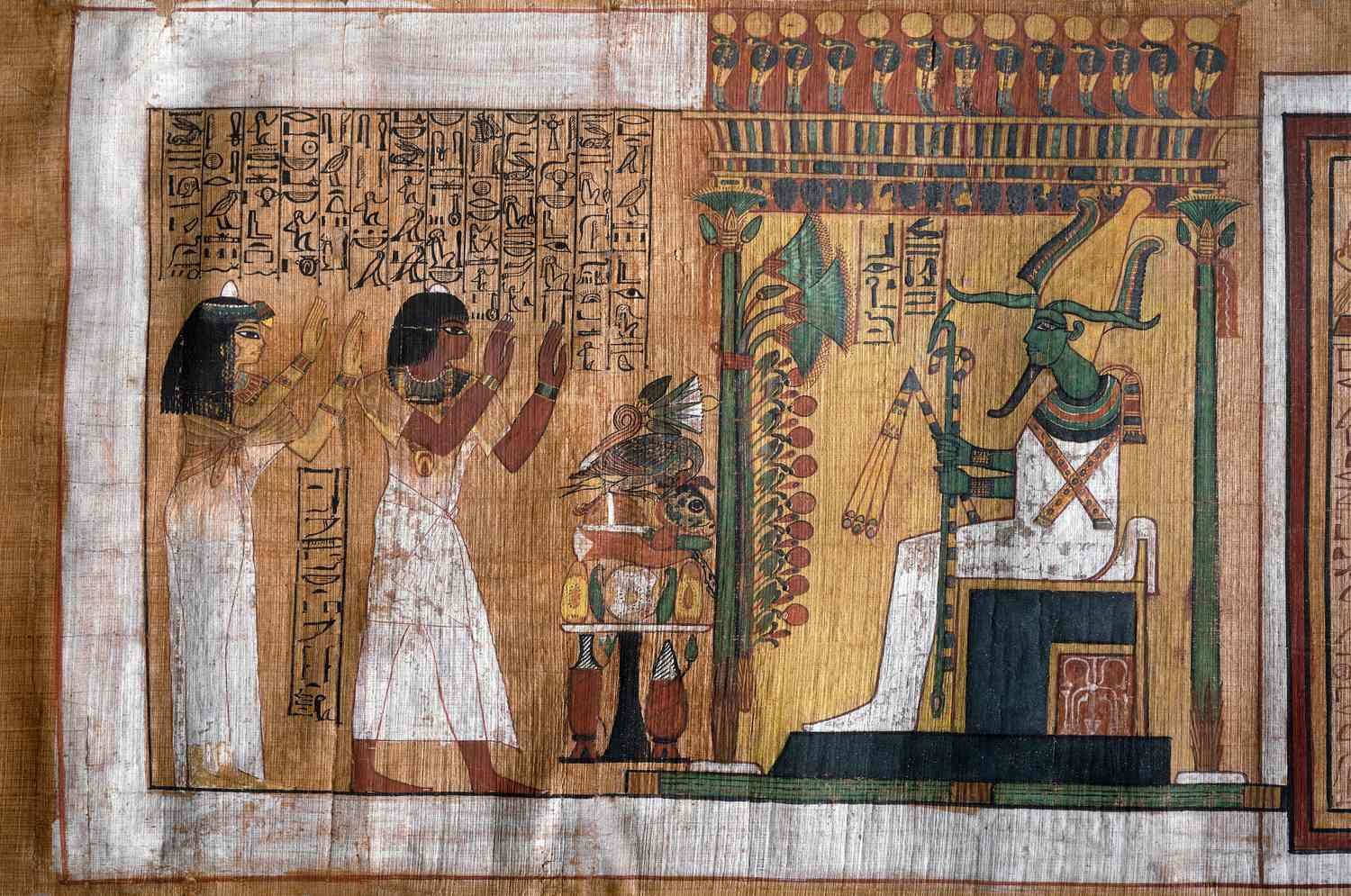

Osiris' Kingdom

Ani, a Theban scribe in the center of ancient Egypt, left a legacy in a scroll, guiding souls through the shadowy passage to Osiris's kingdom. Within a 78-foot papyrus, a route to the afterlife lay alongside him in his tomb, a guide through the perilous Maati. It's a realm where monstrous guardians test the mettle of one's spirit, leading to the court of the 42 divine jurors. Here, one must profess purity with resolute declarations to all its members. The pivotal moment comes as Anubis, god of the dead, weighs your heart against the feather of Ma'at. Should the scales of judgment balance, you’re deemed pure of heart and the fields of Aaru beckon. But should they not, a grim fate awaits: the jaws of Ammit the Devourer.

The privileged few, military men and affluent commoners alike, found their final rest in more ornate sarcophagi. These individuals, often involved in grand invasions or sacred pilgrimages under the Pharaoh's command, bore the weight of earthly transgressions. To shield against any inadvertent misstatements before the divine court, a protection scarab was meticulously placed over the heart during mummification, a talisman against the consequences of minor and major misdeeds.

Ani’s well-preserved papyrus was unearthed in 1888 by Dr. Wallis Budge. Now on display in the British Museum in London, it stands as a testament to the ancient Egyptian 'Book of the Dead'. These texts, penned by priests over centuries, represent some of the earliest known instructional guides for navigating the afterlife, each version a unique reflection of its era.

Throughout the dynastic era of Egypt, the 'Book of the Dead' remained a pivotal guide for the afterlife journey. Its spells, charms, and the recitation of the 42 declarations of innocence were essential for attaining eternal bliss. This sacred content was coveted by all in ancient Egypt, transcending time and social status.

And in the 25th dynasty, as the Nubians reigned over a divided Egypt, they intricately wove elements of this mythos into their own burial practices. The 8th century BCE Shabaka Stone, discovered in 1901 by James Henry Breasted, bears inscriptions of these rituals. Further south, along the Nile in present-day Sudan, detailed instructions from these texts found their way into Nubian tombs, nestled beneath smaller pyramids, marking a cultural blend of traditions.

From the sands of Egypt to China's mystical peaks, the concept of an afterlife deity spans cultures. While the core identities of Egyptian gods and their roles have remained steadfast, China introduces a goddess guiding souls to the afterlife. Though her portrayal has evolved over time, her fundamental promise mirrors that of Osiris, offering a transcultural link in how civilizations perceived life after death.

Xiwangmu and the Shanhaijin

Before the unification of China by Qin Shi Huang around 230 BCE, the land was engulfed in the chaos of the Warring States period. Between 476-221 BCE, the dynasties of Zhou, Qin, Han, Wu, Chu, and Yan fiercely vied for control. This tumultuous era of two centuries not only reshaped the political landscape but also deeply influenced religious beliefs across China, with each victorious empire introducing its own spiritual ideologies, a cycle that repeated with the rise and fall of emperors.

In the times preceding the Warring States period, the Shang dynasty (1600-1046 BCE) succeeded the Xia dynasty (2070-1600 BCE). Archaeological discoveries in the 19th century unearthed turtle shells dating back to these eras. Notably, in the Shandong province, archaeologists found a shell inscribed with ancient script, mentioning a ritual dedicated to Xiwangmu, the "Queen Mother," and her consort Dongwanggong, offering a glimpse into the religious practices of these ancient times.

Xiwangmu, the mythical guardian in Chinese lore, underwent several transformations through the ebb of dynasties, making her origins elusive. She emerged as a guiding spirit for souls in the Han dynasty, a fierce tiger-faced entity in the Zhou dynasty, and a cosmic force in others. Art historian Wu Hung, through Shanhaijing, a Han dynasty-era bestiary, revealed that her depiction was most prominent during this period (202 BCE – 220 CE), indicating her significant cultural impact at that time.

The "Shanhaijing," a pivotal text in Chinese mythology, wasn't written in a single era. Its compilation, coupled with varying accounts of Xiwangmu before and during the early Han dynasty, contributes to the complexity and varied interpretations of her identity, reflecting a rich tapestry of evolving cultural narratives over time.

The Queen Mother of the West

In Han mythology, Xiwangmu tends the legendary peaches of immortality in her garden at Kunlun, which bear fruit once every 3000 years. Consuming these peaches bestows eternal life, granting the eater and their followers a coveted place in her serene garden.

During the journey, the soul embarks on a straightforward path. Post-clinical death, an ox-drawn chariot transports the soul to the Kunlun Mountains. There, under Xiwangmu's nurturing care, the soul awaits its ascension through the Changhe gate to Tai Yi's celestial kingdom.

Xiwangmu's popularity in Chinese mythology likely surged during Emperor Wen-Ti's reign, the third Han emperor known for promoting spiritual freedom. This was a stark contrast to earlier emperors, who imposed stringent controls on spiritual practices. Emperor Gaozu, the dynasty's founder, built an extravagant tomb for himself, showcasing his power. But Wen-Ti, recognizing the burden of such grandeur on his people, chose a simpler mountain burial site, reflecting a more humane approach to leadership.

Wen-Ti also shortened the extended period of imperial mourning, which had stifled social activities across the empire for years after the death of an emperor. His reign marked a significant shift in the spiritual landscape of China, allowing diverse beliefs to flourish. This change in ideology was passed down, influencing subsequent emperors like Wu of Han, Wen-Ti's grandson, who claimed to have consumed a peach of immortality.

Under Emperor Wu's rule, China's connections expanded dramatically. He sent his envoy, Zhang Qian, to establish political ties with the Yuezhi people in Central Asia, inadvertently laying the groundwork for the Silk Road. Zhang's travels likely facilitated cultural exchanges, including spiritual concepts such as Xiwangmu, which some scholars speculate could have contributed to the development of similar deities in other cultures, like Buddha Amitabha in Tibet.

Who is Buddha Amitabha?

Amitabha, a pivotal figure in Mahayana Buddhism's Pure Land tradition, is documented to have emerged in texts from the 1st to 6th centuries CE. His teachings, focusing on the afterlife and rebirth, resonate through Buddhist history. While his influence is acknowledged, the specifics of his impact on Central Asia's religious conflicts and spiritual landscape during this period are not definitively charted. For a comprehensive understanding, delving into academic sources or Buddhist texts is essential.

Buddha Amitabha, a central figure in Buddhism's Mahayana tradition, gained prominence in the Kushan Empire, particularly during Emperor Huvishka's reign (150-180 CE). A key deity in the Mahayana Sutras, written later in the same century, Amitabha's influence spread to China by the 5th century CE. And some historical interpretations suggest that In many regions, he began to eclipse the previously dominant figure of Xiwangmu, showcasing the dynamic evolution of spiritual beliefs across time and cultures.

Amitabha, transcending the concept of a mere deity, embodies a profound Buddhist philosophy: the tathagata, or one who appears before recurrence. He reigns over the Western Land of Bliss, a realm attainable through the crucible of selflessness. This test, open to both the living and the departed, is a journey beyond the self, a quest for a realm where tranquility reigns supreme.

In 1988, anthropologist Wen-Jie Qin embarked on an insightful journey for the documentary "The Revival of Buddhism." Her travels led her to Sichuan, China, where she had the unique opportunity to document a death ritual on the sacred Emei Mountain. This ritual was in honor of a revered monk from the local community who had recently passed away. Her research provided a rare glimpse into the spiritual practices and traditions surrounding death in this region.

In the monastery, as they honored the late Monk Jue Cheng, chants of 'homage to Amita' filled the air, uniting pupils, friends, and family in a solemn ceremony. The procession led to a purifying rite of fire, symbolizing Jue Cheng's soul's ascent to the Land of Bliss. Jue Cheng, far advanced on the path to enlightenment, highlighted the journey to this sacred realm — a path outlined in the Bardo Thodol, accessible even to the ordinary, yet complex in its spiritual navigation.

Bardo Thodol or The Tibetan Book for the Dead

The Bardo Thodol, whose Sanskrit translation means "transition and liberation," was authored by the Tibetan monk Padmasambhava in the 8th century CE. Recognizing the profound and potentially overwhelming nature of its teachings, Padmasambhava concealed the original Thangka, deeming it too intense for that era. Centuries later, his descendant Karma Lingpa discovered it, revealing these profound insights nearly 700 years later.

"Oh nobly born, now thou art experiencing the radiance of the clear light of pure reality. Thine own consciousness, shining, void, and inseparable from the great body of radiance, hath no birth, nor death, and is the immutable light Buddha Amitabha."

This excerpt from the Bardo Thodol introduces the concept of the six bardos, which are essentially a sequence of internal states experienced by the soul. These bardos represent different phases in the journey from death to rebirth, each offering unique spiritual insights and challenges. This framework provides a profound understanding of life, death, and the transition between these states, as viewed through the lens of Tibetan Buddhism.

The first bardo, Kyenay, encompasses the entirety of life, beginning with the first breath and concluding with the last. Within it, the second bardo, Milam, operates as a subset, focusing on the realm of dreams and explored through dream yoga. The third bardo, Samten, is intimately linked with the practice of meditation. Each bardo offers a unique perspective on the continuous journey of existence.

The final three bardos, Chikhai, Chonyl, and Sidpa, are central to why the Bardo Thodol is known as a "book for the dead." Dr. Evans-Wentz named it so in 1927. These stages represent the soul's journey post-death, leading it to Samsara, the cycle of eternal recurrence. Here, the soul encounters countless possibilities for rebirth, ranging from the humble existence of mice to human life or even a Martian being, each choice a window into a new realm and experience.

In the Bardo Thodol, the choice made in Samsara, the cycle of rebirth, is seen as a step towards liberation, achievable in the next life or after a thousand lifetimes. Traditionally, the Bardo Thodol is recited like a hymn to the dying, often by a monk, guiding them through resisting the vivid visions encountered in Samsara. These visions, celestial Buddhas transforming into reflections of one's ego, represent a profound journey of the soul through the bardos.

The soul initially encounters joyous visions from past and potential future lives. These experiences gradually transform, with celestial Buddhas morphing into daunting, nightmarish figures uttering terrifying words. This shift in vision serves to test the soul, potentially trapping it in the cycle of Samsara. An enlightened soul, on the verge of liberation, perceives these images as mere illusions, understanding their true nature as ephemeral and non-threatening. This comprehension is key to breaking free from the cycle and moving towards enlightenment.

The Silk Road, a bustling network of trade from its inception until the 12th century CE, was a crucial conduit for the exchange of not only spices, jewels, and fabrics across Asia, but also of ideas and beliefs. It facilitated the spread of concepts from Xiwangmu and Amitabha, intertwining these spiritual narratives with the rich tapestry of trade, eventually reaching European cities via the Mediterranean Sea. This exchange illustrates the profound interconnectivity of cultures and religions along this historic route.

As the Silk Road facilitated the intermingling of cultures and ideas, it also unwittingly became a conduit for disease. The Xenopsylla Cheopis, a type of parasitic flea thriving in subtropical regions, was stirred into activity by the vibrations of the bustling trade caravans. These tiny pests, feeding on the traders and their animals, became unwitting carriers, spreading illness along the trade routes. This unforeseen consequence highlights the complex and sometimes perilous interplay between human endeavors and the natural world.

In the 14th century, the cramped and unsanitary conditions below the decks of trading ships created a breeding ground for black rats. These rats, infested with fleas, including the Xenopsylla Cheopis, became accidental couriers of the parasites as they disembarked at various European ports. This unfortunate combination of trading practices and unchecked vermin populations played a key role in spreading diseases across the continent.

The black rats aboard these ships were carriers of the Black Plague, a devastating pandemic that claimed up to 110 million lives from 1346 to 1353. The plague continued to recur with diminishing severity until 1671, ultimately resulting in around 200 million deaths. This tragic episode in history highlights the profound impact of disease on human civilization.

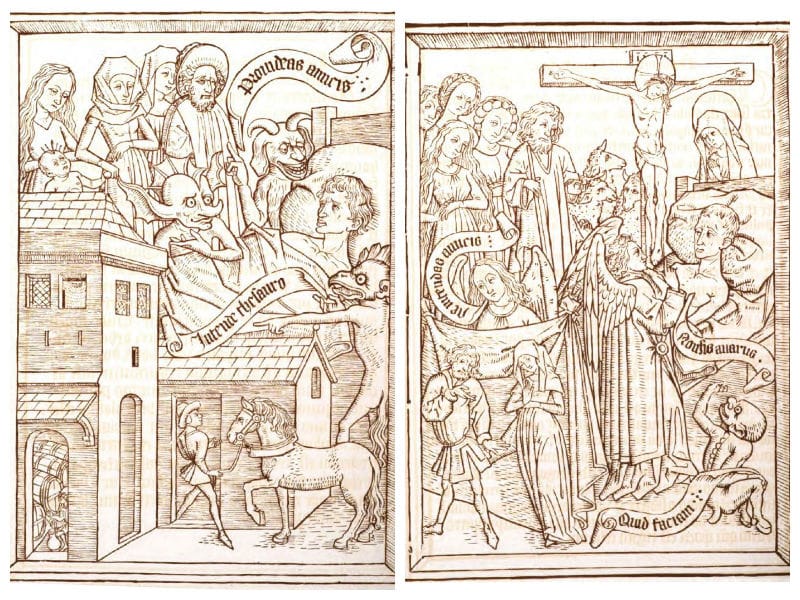

In the early 15th century, block books, made from woodcuts and dried leaves, became a prominent medium for disseminating information. About a century after the Black Plague, the Catholic Church published the block book "Ars Moriendi" or "The Art of Dying Well," filled with prayers in medieval Latin. A shorter, more artistic version was later released in the mid-15th century, reflecting the era's evolving approach to literature and spirituality.

During the Middle Ages (5th to late 15th century), with a predominantly Christian population in central Europe, the scarcity of bishops and priests made it challenging to attend to the spiritual needs of the dying. To address this, religious ministers in Rhenish Germany began creating engraved writings of "Ars Moriendi" to guide Christians towards a dignified end. This work saw widespread reproduction and expansion, with notable contributions from figures like Johann Geiler and Martin Luther.

"Ars Moriendi," a pivotal guide from the Middle Ages, instructs on resisting the five temptations faced during the dying process: lack of faith, despair, greed, pride, and impatience. The text vividly depicts a dying man's struggle with these temptations, offering a window into the spiritual journey towards a dignified death.

The Art of Dying Well

In the illustrated version of "Ars Moriendi," the book takes the form of a collection of prayers, each slightly different in content. As a guide for those at death's door, it prescribes specific prayers to Christian deities like Jesus Christ and The Virgin Mary. The dying, in their final moments, are encouraged to acknowledge these blessings in any way possible. In cases of critical condition, the focus is solely on the prayers dedicated to Jesus Christ, underscoring the depth of spiritual comfort sought in the twilight of life.

In the artistic rendition of "Ars Moriendi," each right page features an illustration of a bedridden man, surrounded by hospice care, angels, demons, or a combination of these. On the left, the margins are adorned with prayers written in Medieval Latin. These prayers detail the various temptations faced in death and the ways to overcome them, offering a poignant guide for the soul's final journey. This layout merges visual narrative with spiritual guidance, reflecting the book's profound role in medieval Christian practices.

In the "Ars Moriendi," the illustrations depict the emotional journey of a dying man. Early pages show him in distress, agitatedly overturning a table and appearing to resist care. Contrastingly, other pages present him at peace, surrounded by holy figures like Jesus, The Virgin Mary, and various saints in prayerful vigil. Amidst this serene assembly, demons begin to emerge, some crawling from beneath his bed, others confronting him, and a few lurking behind the saints, creating a striking visual narrative of the struggle between salvation and temptation at life's end.

In the "Ars Moriendi," further illustrations capture the man's confusion and discomfort as demons, wielding utensils, weapons, and crowns, tempt him. He appears impatient, reaching for these worldly items, while angels beside him maintain their prayerful stance, eyes closed, embodying a serene contrast to the chaotic temptations presented by the demons. This juxtaposition visually narrates the inner turmoil of the dying man, caught between the allure of earthly temptations and the tranquility of divine presence.

As the narrative unfolds in the "Ars Moriendi," the man oscillates between consciousness and unconsciousness, with some pages featuring only saints, others only demons, and some depicting both. The purpose of the prayers is to soothe the dying, guiding them towards a peaceful acceptance of their fate, contrasting with the demons' efforts to incite struggle. This juxtaposition between the saints' contentment and the demons' provocations vividly illustrates the eternal battle between good and evil, and the choice between resistance and acceptance at life's end.

How do these diverse cultural approaches to death and the afterlife reflect on our current understanding and attitudes towards mortality? From the ancient Egyptians with Osiris, the Chinese with Xiwangmu and Amitabha, to the medieval Christians and their "Ars Moriendi," what can we learn about the way our ancestors viewed the end of life, and how might this influence our modern perspectives on this universal human experience?