How a Wrong Turn Started World War I

A Sunny Sarajevo Morning, A Fateful Shot

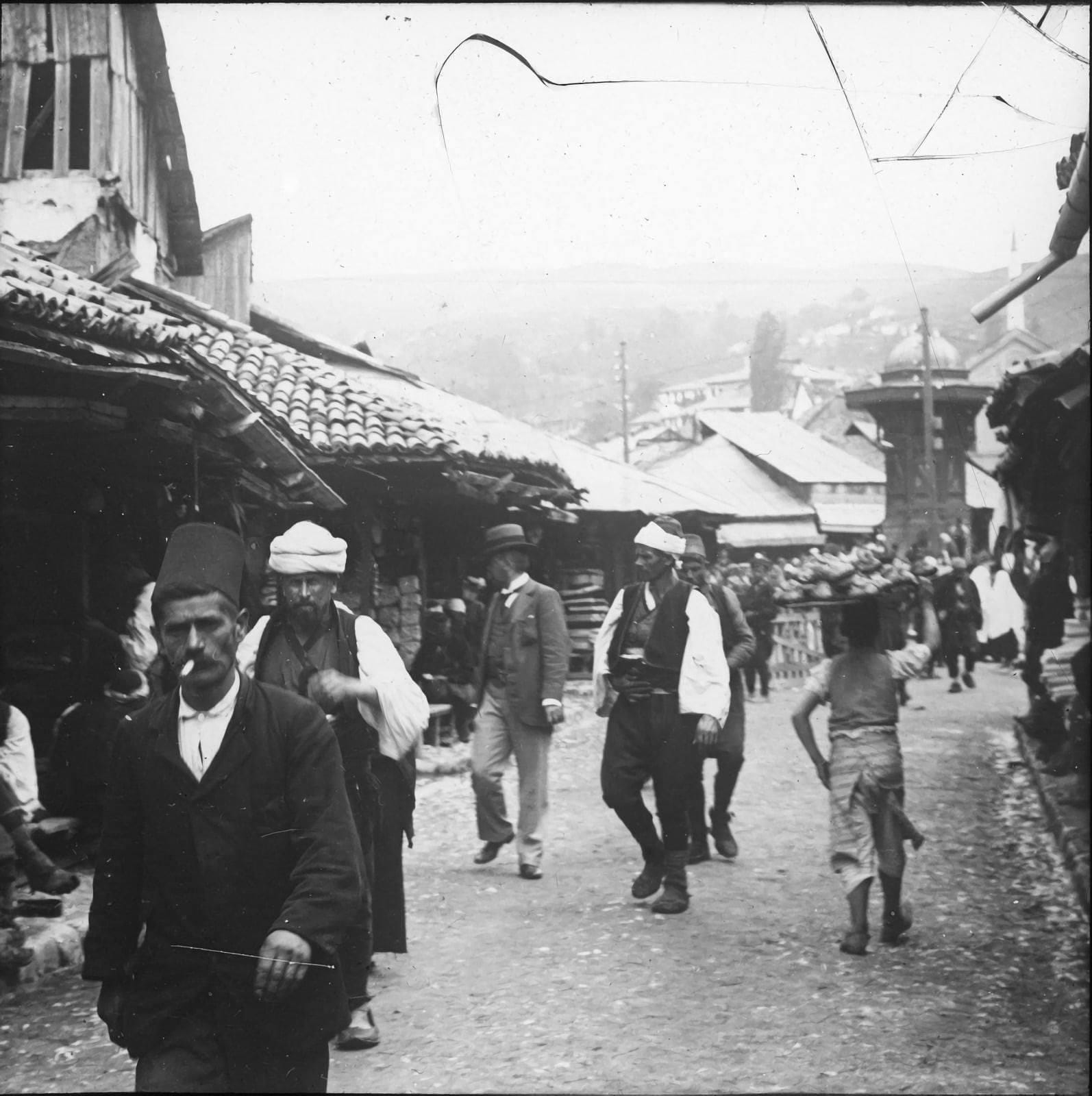

Sarajevo, June 28, 1914. The morning is sunny and warm, with Austrian flags fluttering alongside flowers on the crowded Appel Quay. An open-topped car processes down the boulevard, carrying Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria and his wife Sophie. Cheers ring out for the imperial couple – but mingling in the festive crowd are seven young men with assassins’ tools hidden in their pockets.

Among them is 19-year-old Gavrilo Princip, a Bosnian Serb teenager with fire in his heart and a pistol in his hand. Suddenly, crack! – two gunshots shatter the summer air. In an instant, the Archduke and his wife slump in their seats, fatally wounded by Princip’s bullets. In that split-second, Europe veers off course.

A wrong turn and a teenager’s trigger finger have just lit the fuse of a catastrophe.

Could a single shot really change the world? As panic and pandemonium erupt on the streets of Sarajevo, the answer will ripple far beyond Bosnia. Those gunshots became the prelude of World War I, sending shockwaves from Vienna to Italy and across all of Europe in 1914. The course of the World War 1 timeline is about to begin.

Young Bosnia’s Rebel and an Empire on Edge

Who was Gavrilo Princip, and what drove this gaunt, tuberculosis-stricken teen to assassinate a royal? To understand, we must step back into the tense landscape of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the Balkans in the early 20th century.

Princip was born in 1894 to a poor farming family in Bosnia – a province that had fallen under the rule of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. By 1914, the empire had become a sprawling patchwork of peoples and simmering resentments. It spanned from the refined streets of Vienna to rural villages in Galicia, ruling over nearly 51 million subjects of myriad nationalities. Czechs, Slovaks, Poles, Ukrainians, Italians, Hungarians, Romanians, Croats, Serbs – all lived under the Habsburg crown. (Indeed, the Czech Republic’s population today descends from subjects of Franz Josef’s arena back then.)

Bosnia-Herzegovina, with its mix of Serbs, Croats, and Bosniak Muslims, was one such province – annexed by Austria-Hungary in 1908 against local wishes. For young nationalist students like Princip, Bosnia was a captive nation straining in the grip of a multi-national empire.

Princip came of age chafing under foreign rule. In school, he devoured nationalist poetry and revolutionary ideas. As a teenager, he even tried to join guerrilla fighters in Serbia during the Balkan Wars of 1912, eager to fight the Ottoman Turks – but he was rejected for being too small and weak.

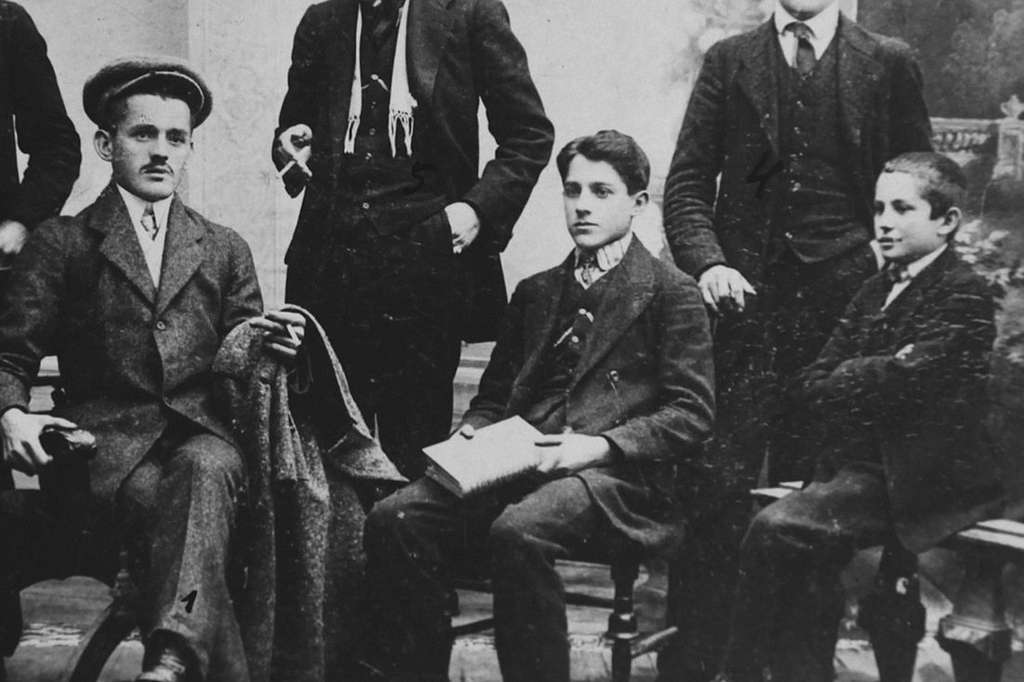

What Princip lacked in stature, he made up for in determination. By 1914, he had fallen in with a secretive youth movement called Mlada Bosna (“Young Bosnia”), a group of idealistic Bosnian Serb, Croat, and Muslim students united by one goal: to free their homeland from Austro-Hungarian occupation. They dreamed of shedding imperial shackles and uniting all South Slavs (Serbs, Croats, Slovenes, and Bosnians) into a single, independent nation. A Yugoslavia – literally a South Slavic state – was their vision, and they were willing to die for it.

Across the border in the Kingdom of Serbia, many applauded this dream. Some even offered covert help. A shadowy Serbian secret society, known as the “Black Hand” (led by Serbian military officers), armed and trained Princip and his co-conspirators. Princip learned to fire pistols and make bombs, contiually steeling himself to do something drastic.

By June 1914, Gavrilo Princip was a 19-year-old on a mission, gaunt from poverty but fueled by nationalist fervor. He saw the Habsburg rulers as oppressors and believed a dramatic act of violence could awaken his people. “If I don’t do it, who will?” he must have thought. When Princip learned that Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, was coming to Sarajevo for a state visit, he and his Young Bosnia comrades seized the opportunity.

The Archduke was viewed as a symbol of imperial might. To Princip, striking him down would be like slaying the dragon threatening his homeland. The date of the visit felt almost predetermined: June 28 was Vidovdan (St. Vitus’ Day), a sacred Serbian holiday marking an ancient battle against the Turks.

What better day for a South Slav nationalist to strike a blow? Princip and his friends, with weapons supplied via the Black Hand, quietly slipped into Sarajevo and staked out positions along the Archduke’s parade route. Each carried a revolver, a bomb, and a vial of cyanide for suicide if caught. They were young (some still teenagers), zealous, and ready to gamble with their lives to change their country’s fate.

Europe on a Knife’s Edge in 1914

It wasn’t just Bosnia that was a cauldron of discontent – Europe in 1914 was a continent loaded with rivalries and grievances. Decades of imperial competition had split the great powers into opposing camps.

On one side stood Austria-Hungary and its ally, Germany; on the other, Serbia’s larger Slavic neighbor, Russia, was allied with France and Britain. These alliances meant that a conflict in one corner of Europe could quickly drag in others – a dangerous “cascade of diplomatic alliances” primed to turn a local quarrel into a general war.

Leaders in the Austro-Hungarian capital Vienna, were increasingly anxious about the empire’s future. Their territory was beset by nationalist movements (like Young Bosnia) from within and challenged by Serbia’s rising influence in the Balkans. Just two years earlier, in 1912–13, the Balkan Wars had resulted in Serbia nearly doubling in size after defeating the Ottoman Empire. Serbian politicians made little secret of their desire to see Bosnia (with its Serb population) join a “Greater Serbia.” To Vienna’s aging emperor Franz Josef, Serbia looked like a meddlesome little brother stirring up his South Slav subjects – a direct threat to Austro-Hungarian authority.

In Italy, meanwhile, opportunism hung in the air. Italy was nominally allied with Austria-Hungary and Germany in the Triple Alliance, but it had its own designs on Austrian-held territories (like Trieste and Tyrol, areas with Italian speakers). Italian leaders watched the tensions with a calculating eye, wondering if a war could let them snatch land from Austria. From Vienna to Italy, from the Russian border to the French frontier, Europe’s capitals were on edge. It was as if the whole continent was a row of dominoes standing upright – one push and the lot would come tumbling down. Europe in 1914 was armed to the teeth, every nation flexing its military might. Kaiser Wilhelm’s Germany stood ready to back Austria-Hungary unconditionally, even if it meant confronting Russia. Across the continent, millions of soldiers drilled and generals drew up war plans. Yet, no one wanted to be seen as the aggressor; they only awaited the right pretext.

That pretext was about to be provided on a Balkan street corner. The Austro-Hungarian government, hoping to cow Serbian ambition, arranged for Archduke Franz Ferdinand to inspect imperial troops in Bosnia’s capital, Sarajevo – a very public display of Habsburg power on Serbia’s doorstep. Franz Ferdinand’s visit was also meant as a goodwill tour to reassure Bosnia’s people that they were valued parts of the empire. But choosing June 28 for the royal visit was a provocative twist of the knife: on this Serbian holy day, the sight of an Austrian archduke parading through Sarajevo felt like an insult to many South Slavs. Local Bosnian Serb nationalists seethed; secret societies in Belgrade whispered of revenge. Despite warnings of danger, the Austrians forged ahead with minimal security. Archduke Ferdinand, a proud man not easily frightened, brushed off concerns – he hated being told what to do. When advised it might be risky to go, he snapped, “Don’t be ridiculous,” and stuck to his schedule. And so, on that late June morning, a cavalcade of automobiles set out through Sarajevo’s streets, bearing Franz Ferdinand and Sophie in regal pomp straight toward the jaws of conspiracy.

The Assassination: A Wrong Turn, a Fatal Moment

The Archduke’s motorcade rolled along Sarajevo’s Appel Quay like a target in a shooting gallery. Lining the route, hidden in plain sight among curious onlookers, Princip and his six co-conspirators gripped their weapons and waited. At 10:15 AM, as the cars passed the first assassin’s position, nerves faltered – one young plotter couldn’t go through with it. But moments later, near the Cumurja Bridge, 19-year-old Nedeljko Čabrinović found his courage. He hurled a hand grenade at Franz Ferdinand’s car. The Archduke saw something flying toward him – bang! – the bomb bounced off his car’s folded convertible top and exploded under the following vehicle. Shrapnel and shockwaves hit the crowd; an officer in the next car was severely wounded. In the chaos, Čabrinović gulped down his cyanide pill and jumped into the Miljacka River to kill himself – but in an almost comic failure, the poison was old and only made him vomit. The river was a muddy puddle too shallow to drown in. Sarajevo police dragged the sputtering would-be assassin from the water, and Franz Ferdinand’s procession sped away, shaken but unharmed.

One attempt had failed, but the day was far from over. Instead of canceling the visit, the irritated Archduke insisted on continuing his schedule – he even attended a reception at City Hall, where he angrily scolded the mayor, “I come here as your guest, and your people greet me with bombs!” Only after this tense encounter did Franz Ferdinand agree to change his plans: he would visit the hospital to see those injured by the bomb and then leave the city. His staff decided to avoid the crowded city center and take a safer, alternate route along the river.

But crucially, this change of route was not communicated to all the drivers. As the motorcade departed around 11 AM, the lead car mistakenly turned off Appel Quay onto a side street – Franz Joseph Street – directly into the old downtown area. In the second car, General Oskar Potiorek (Bosnia’s governor) shouted to the driver that he was going the wrong way. The driver hit the brakes and began to reverse – and at that exact moment, life's director intervened.

By sheer chance, Gavrilo Princip was standing right there on that very street corner, near a deli shop, still lingering after the failed bombing attempt. He had been loitering in despair, thinking his chance was lost. Now, the Archduke’s car suddenly halted a few feet from him.

Seizing the moment, Princip stepped forward, raised his Browning pistol, and fired two shots at point-blank range into the car. His aim was deadly. The first bullet struck Franz Ferdinand in the neck; the second hit Sophie in the abdomen. “If Princip had spent his entire life studying human anatomy, he couldn’t have placed his shots better,” historian Christopher Clark observed of the assassin’s uncanny, lethal precision.

The Archduke let out a strangled cry, “Sophie, don’t die – stay alive for our children!” but within minutes, both husband and wife had bled to death inside the limousine.

Princip was swarmed and pinned to the ground by enraged bystanders and police (one man struck him twice in the face, nearly killing him on the spot). The 19-year-old shooter was arrested with the smoking gun still in his hand – his grim task accomplished. In the blink of an eye, a teenage revolutionary from the shadows of Young Bosnia had done the unthinkable by assassinating the heir to one of Europe’s oldest thrones. He had wanted to strike a blow for his people’s freedom, and he succeeded beyond his wildest dreams – and fears.

As Princip was hauled off to jail amid roaring crowds, he surely could not imagine the inferno that would soon engulf the world as a result of his act.

Thunderbolts of War, Empire Collapse, and a World Remade

The immediate aftermath of the assassination was a mix of shock, outrage, and diplomatic frenzy. Austria-Hungary, thirsting for revenge, quickly concluded that Serbia was behind the plot (after all, the guns and bombs had Serbian origins, and one assassin had ties to Serbian military intelligence). One month later, on July 28, 1914, Vienna sent an ultimatum to Serbia and, unsatisfied with the response, declared war, determined to crush its troublesome neighbor.

The chain reaction began: within days, Russia mobilized to defend Serbia, and Germany, honoring its pact, declared war on Russia and France; Britain, in turn, declared war on Germany after the violation of neutral Belgium. By early August 1914, what might have been a local Balkan conflict had escalated into a full-fledged Great War involving all the major powers. As one historian described it, a “cascade of alliances” dragged almost the entire continent into battle. The war that ensued – World War I – would last over four years, consume millions of lives, and topple mighty empires.

And what of Gavrilo Princip, the young man who started the fire? He did not get to revel in any triumph. Princip and his captured co-conspirators were put on trial in Sarajevo in October 1914. Facing Austro-Hungarian justice, Princip remained defiant, but fortune spared him the gallows. By imperial law, the death penalty could not be applied to anyone under 20, and Princip was 19 at the time of the assassination. Instead, he received a 20-year prison sentence – the maximum allowed.

Princip was dispatched to a grim fortress prison in Theresienstadt (in northern Bohemia, in what is now the Czech Republic). There, harsh conditions did what the executioner could not. Princip was likely already tubercular when incarcerated, and confinement made it worse. He endured solitary darkness, inadequate food, and disease. The tuberculosis spread to his bones; his infected arm had to be amputated to save his life. But nothing could save him in the end. Less than four years after his moment of infamy, Gavrilo Princip’s cause of death was recorded as tuberculosis – he died on April 28, 1918, frail, in pain, and weighing barely 40 kilos.

Princip’s last days were haunted by what he had unleashed. On the walls of his cell, he scratched a final prophecy: “Our shadows will walk through Vienna, wander the court, frighten the lords.” Indeed, even as he perished, the metaphorical shadow of this teenager loomed over Vienna’s imperial court – and it was about to bring that court crashing down.

By late 1918, World War I had burnt itself out, and Princip’s prophecy was realized in full. Austria-Hungary, the centuries-old Habsburg empire, lay in ruins – it simply disintegrated under the strain of war and internal revolt.

The same fate befell the German, Russian, and Ottoman Empires: all collapsed by the war’s end. A new political order came from the rubble. Look at a map of post-World War 1 Europe, and the changes are stark. The victorious Allies redrew national borders from the North Sea to the Middle East. Austria-Hungary vanished from the map, replaced by a constellation of new or reborn nations. From the empire’s Slavic provinces, a Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes was created – soon known as Yugoslavia, the South Slavic state Princip had dreamed of. Austria and Hungary became separate, shrunken countries. The Czech and Slovak peoples formed Czechoslovakia, freeing the former imperial subjects in Prague and Bratislava (the Czech Republic’s population and their Slovak neighbors) from Habsburg rule. Poland reappeared as an independent nation. Romania gained Transylvania; Italy seized South Tyrol and Trieste. The Ottoman Empire’s Middle Eastern lands were carved into new states under European supervision.

In short, the map of Europe underwent a profound transformation in 1918–1919 as a direct consequence of World War I. Borders that had survived for centuries were erased, and new flags were raised over lands that had long been oppressed.

Gavrilo Princip did not live to see it, but his bullets triggered the very outcome he had desired: the end of Austro-Hungarian rule in the Balkans. Bosnia was liberated from Vienna’s clasp – although rather than becoming independent, it was folded into the new Yugoslavia under a Serb-dominated monarchy. (The blue-white-red Yugoslavia flag would fly over Sarajevo for decades to come, uniting South Slavs under one banner.)

The Habsburg double-headed eagle that had lorded over Bosnia was replaced by the tricolor Bosnian coat of arms within the Yugoslav Federation and, much later, by the Bosnian flag of an independent Bosnia and Herzegovina after Yugoslavia’s breakup in the 1990s. In a broader sense, Princip’s shots rocked the world: they led to a war that claimed nearly 15 million lives and left a generation traumatized. The world war timeline from 1914 to 1918 is strewn with apocalyptic battles – the Marne, Verdun, the Somme, and Gallipoli – all cascading from the events in Sarajevo. The Austro-Hungarian Empire, which once sprawled confidently across Central Europe, was now just a memory consigned to history books and old maps of the empire. As one era died, a new and uncertain one was born, all in the aftermath of a young radical’s act on that Sarajevo street.