The First Nubian King Of Ancient Egypt: Piye

In the scorched lands by the Nile, Nubia's ancient culture began influencing Egypt's destiny in the eighth century B.C., giving birth to Egypt's 25th dynasty—a pivotal period in the Late Period. When their grip on Egypt waned, the Nubians founded the thriving Kingdom of Kush in isolation, becoming a cultural beacon as Egypt faced invasions.

Meroe, a city of Nubian kings and queens, is a monumental testament to Nubia's grandeur, marked by pyramids and recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage site. This once-great capital mirrors the might and elegance of a civilization that still fascinates scholars and explorers.

In exploring Piye's rule, he was the king of Nubia and later conquered Egypt when lower Nubia was in danger by Tefnakht I and his kinglets. Piye's victory stele at Jebel Barkal emerges as a vital artifact, standing near Napata and dating to c. 725 B.C. This stele, a window into a time of strife and conquest, details Piye's triumphs in hieroglyphic script, with translations and interpretations available in key works on ancient Egypt.

In the coming sections, we'll delve into this artifact's intricacies, unveiling the complexities of Piye's rule and the legacy of the Kingdom of Kush.

Introduction to Piye's Era and the Rise of the Kingdom of Kush

The dunes of modern Sudan house the remnants of a once-powerful civilization. The city of Meroe, marked by its towering pyramids, was the capital of the Kingdom of Kush. This thriving civilization played a decisive role in shaping Egypt in the 8th century B.C., even serving as Egypt's 25th dynasty in the Late Period.

In this cultural exchange and rivalry context, the Kingdom of Kush emerged near Mount Barkal between the third and fourth Nile cataracts. Piye ruled this kingdom from about 750 to about 719 BCE, laying the groundwork for Egypt's 25th dynasty, first ruled by his brother Shabaka. The cult of Amon Re deeply resonated with the Kushites because, for the Nubians, Amun was associated with protecting Kushite kingship, and it was this devotion that soon propelled Piye's military actions.

Known formerly as Piankhi, Piye's ascension to dominion in Egypt came at a time of division and fragmentation within Lower Egypt. At the time, you had four Libyan overlords designating themselves Pharaoh and ruling separate principalities. Dynasty XXII was ruled by Osorkon IV in Tanis, Dynasty XXIII under Iuput II at Leontopolis, Namlot of Hermopolis, and Dynasty XXIV by Tefnakht from Sais - The Great Chief of the West. Piye's motives extended beyond territorial ambitions; they were entwined with spiritual connections to Amon Re, the Egyptian god of the Sun, so the threat by Tefnakhte to Amon's homeland in Upper Egypt became a trigger for Piye to march northward from the Nubian capital Meroe.

The Libyan prince of Sais in Lower Egypt, Tefnakht, steadily advanced upstream in the west of the Nile valley and on the Bahr Yusuf, a canal connecting the Nile to the city Faiyum, and triggered a significant change in the region's power dynamics. His conquests bypassed Heracleopolis and reached the Oxyrhynchus nome, provinces of ancient Egypt each ruled by a chief or Nomarch, capturing several areas, including Crocodilopolis and Medum. Many nome chiefs capitulated under his violent behest, but Tefnakht avoided eastern regions until securing key nomes, like Ankyronpolis and Aatfih. Despite his impressive advancements, Tefnakht wisely avoided confrontation with Piye, maintaining the common southern frontier of Upper Egyptian nomes.

Namlot, king of Hermopolis and ally of Piye, also shifted his allegiance to Tefnakht, probably foreseeing the fall of Heracleopolis and the threat to his capital. He tore down the fortifications of his city, Nefrusy, allying with Tefnakht. Tefnakht's decision not to invade Piye's sphere of influence demonstrated political savvy. Still, Namlot's defection, the failures of many kings in Middle Egypt, and the plea for help to Piye by the faithful king Peftjaubast of Heracleopolis marked the beginning of a very turbulent era.

The Military Campaign Against the Libyans

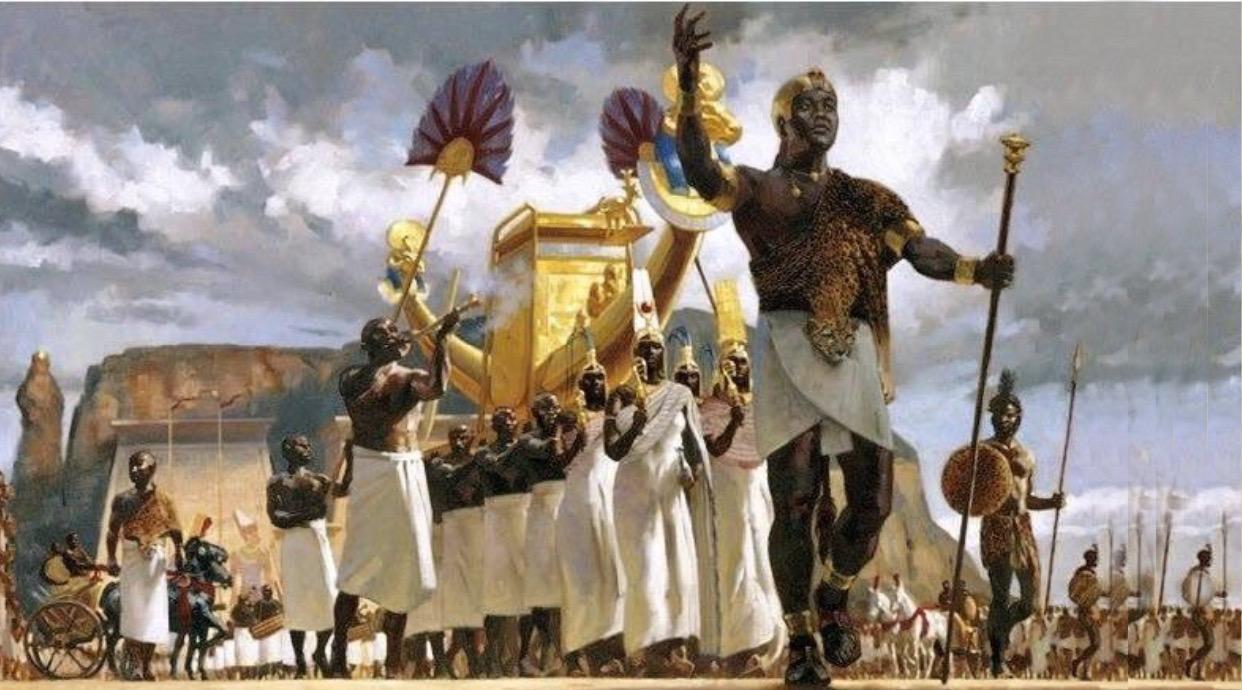

Piye's military campaign against the Libyans was a meticulously planned operation that began after a symbolic and ritual visit to Thebes, a vital spiritual center for the Egyptians and Kushites alike. His forces first encountered the Libyans' river fleet on the Nile, deploying a combination of strategic insight and seasoned warriors to earn a decisive victory. This triumph on the waterways was more than just a battle won; it sent a powerful message of Piye's might and determination.

Following this naval success, Piye's forces marched towards Heracleopolis, where another significant battle unfolded. Tefnakht's aggressive march upstream had bypassed Heracleopolis, but Piye was determined to secure the region. The ensuing battle near Heracleopolis resulted in the vanquishing of the Libyan land army, demonstrating the Kushite's superiority on both water and land.

The victorious Kushite forces then pressed on, advancing to key strategic points like Hermopolis and Memphis, Egypt's ancient capital. Along the way, Tefnakht's captures in the western Delta, including Oxyrhynchus and other nomes, were methodically reclaimed by Piye's disciplined troops. The once formidable Libyans were now in retreat, and the Kushite juggernaut seemed unstoppable.

Piye's success led to the submission of multiple delta rulers, including prominent figures like Namlot, the prince of Hermopolis, who had initially sided with Tefnakht. Even the last representative of the 23rd dynasty recognized the futility of resistance, yielding to Piye's authority.

The climax of the delta invasion marked a turning point in Piye's campaign. More cities and nomes surrendered, and Tefnakhte, who had once posed a substantial threat, was forced into submission, swearing an oath of fealty to Piye. This submission was a military triumph and a complex interplay of politics, cultural heritage, and religion, reflecting Piye's ambitions beyond mere conquest.

Throughout the campaign, Piye's actions were calculated and nuanced, motivated by a desire to preserve the spiritual and cultural integrity of the region, rather than just territorial gains. His victories were instrumental in galvanizing the Delta into a united entity and sparking a nationalistic feeling among its inhabitants, reshaping the political landscape of Egypt during the eighth century.

Tefnakht's failure to fully invade Piye's sphere of influence, his avoidance of confrontation, and the strategic retreats were not enough to counter the Kushite king's successful campaign. Piye's actions resonated with profound implications for Egypt, laying the groundwork for a new era of Kushite influence and control, an era marked by a complex blend of spiritual allegiance, political intelligence, and cultural preservation.

Reflection

Piye's campaign, chronicled in his victory stela, is more than a tale of military conquest; it’s a complex narrative that unravels the era's geopolitical, cultural, and spiritual intricacies. Piye's concern for tribute, indifference to the Delta Egyptians' independence, and lack of intention for a full conquest paint a vivid picture of a ruler guided by pragmatic and spiritual interests.

The Kushite king's influence extended beyond his reign. His actions, driven by belief and necessity, shaped the political landscape, leaving a legacy that resonated throughout Egypt and Kush. The echoes of Piye's deeds, as told through the stone of his victory stela, continue to resonate as a powerful testament to the grandeur of ancient Nubia and its lasting impact on the region.

The Pyramids of Nubia

Roughly 200 years before Piye’s time, the ancient Egyptians withdrew from the Napata region after sacking it. They left an enduring imprint that melded with indigenous customs, giving rise to the kingdom of Kush. This complex fusion of traditions led to the establishment of Meroe (800 BC – BCE 350), situated on the east bank of the Nile in southern Nubia, near Shendi, Sudan.

Meroe was an emblem of the Nubian civilization that preserved many ancient Egyptian customs yet developed its own unique character. The people of Meroe not only adopted Egyptian religious practices but also adapted Egyptian writing, initially embracing hieroglyphs and eventually creating an alphabetic script with 23 signs, reflecting a culture rich in innovation.

The Nubian pyramids, particularly those in Meroe, serve as both symbols of this complex heritage and distinct markers of divergence from Egyptian civilization. Unlike Egypt’s pyramids, Nubia’s are steeper and more huddled, spanning 600 miles of Sudan, and found in four clusters around sacred sites. Their enigmatic nature remained a mystery until studies by an architect named Hinkel unraveled differences from their Egyptian counterparts. The Nubian pyramids echo the legacy of the 25th Dynasty's founder, who conquered Egypt, possibly drawing inspiration from smaller private Egyptian pyramids from the 18th Dynasty.

The kingdom of Meroe was not without its military prowess, consisting of an impressive standing force that, under the leadership of King Piye, invaded and controlled Egypt in the 8th century as the twenty-fifth dynasty. The Kushites held sway over their northern neighbors for nearly a century before being forced to move farther south by the Assyrians. Their influence extended to monumental architecture. Nubian kings like Taharqa, a son and third successor of Piye, restored Egyptian temples at Karnak and built new temples and pyramids in Nubia.

The history of Meroe’s pyramids is tinged with the misadventures of treasure hunters like Guiseppe Ferlini, who ventured into Sudan in 1834. His claim of finding Queen Amanishakheto’s jewelry at the top of a pyramid spurred others to decapitate the pyramids in a futile search for treasures. Though met with skepticism, the authenticity of the jewelry was eventually vouched for, and Nubian jewelry became highly prized.

Meroe's power, however, was not unchallenged. Strabo's accounts describe clashes with the Romans, leading to defeats and a series of territorial battles. The region fragmented into smaller groups, with generals commanding small armies of mercenaries. This left the region vulnerable, and Meroë eventually met defeat by a new rising kingdom to their south, Aksum, under King Ezana.

In reflecting upon the Nubian pyramids and the capital of Meroe, one encounters a vivid testament to the region's layered history, symbolizing continuity with and divergence from ancient Egypt. This multifaceted story resonates with the complex interplay of power, influence, treasure-hunting, cultural preservation, and the broader tapestry of Nile Valley civilization, a narrative that gracefully intertwines the historical intricacies of Nubia's relationship with Egypt and the unique identity it forged in the shadow of its powerful neighbor.

Nubia's History

Northeastern Africa, the region of Nubia stands as a sentinel of history and culture. Stretching along the timeless Nile river and nestling in the embrace of present-day northern Sudan and southern Egypt, Nubia's history can be traced back to at least 2000 B.C. through relics, inscriptions, and a whisper of tales passed down through generations.

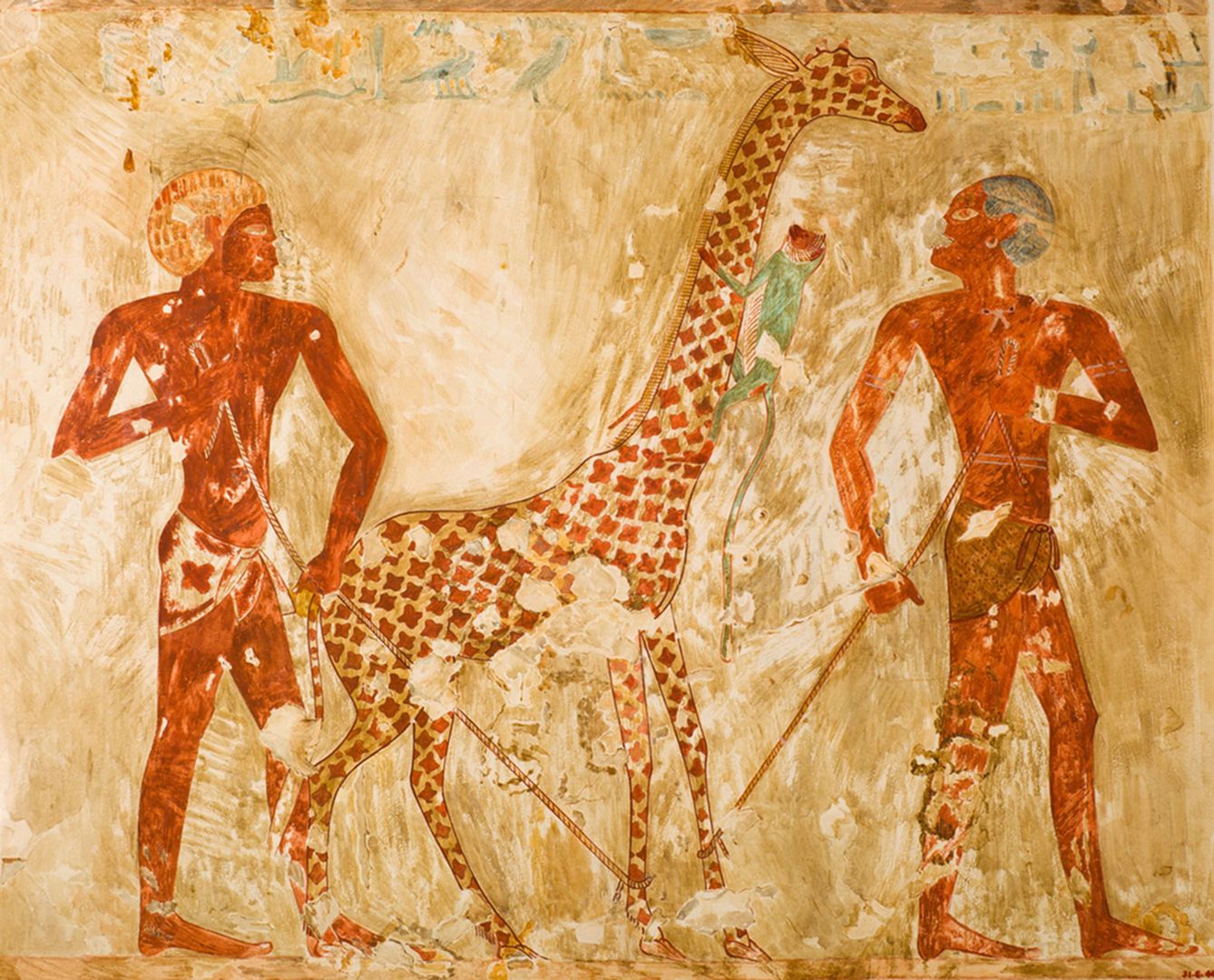

Known as the "Land of the Bow" or Ta-Seti on the tongues of the ancient Egyptians, Nubia was a realm of masterful archers. The art etched into Nubian rock from the Neolithic period sings songs of hunters drawing bows and loosing arrows. Their mastery was not limited to the hunt, where ivory and animal skins were prized spoils. The bow was a symbol of power, heritage, and skill that resonated through the echoes of time.

Archers of Nubia were no mere hunters. They were warriors, the backbone of armies that vied with Egypt and later conquered its lands. Such was their prowess that ancient texts dating back to 2400 BC heralded their place in the military, both in the Egyptian and grand Persian imperial army.

The pages of history reveal that in the 5th century BCE, Nubian rulers were still laid to rest with bows by their side. The bow was not only a tool but an emblem of their identity. In an era when warriors rode into battle with arrows guided by thumb rings, the Nubian archers were feared and respected, even successfully fending off Muslim invaders in the 8th century.

The land of Nubia was more than its warriors. It was a civilization of depth and diversity, home to great kingdoms and empires that flourished and fell. The last of the mighty Nubian kingdoms collapsed in 1504, dividing the land and its people, and leading to a period of Arabization.

Throughout time, Nubia saw many changes. It united with Ottoman Egypt in the 19th century and later within the Kingdom of Egypt, a land forever caught between past and present. Its name is derived from the nomadic Noba people who settled the land in the 4th century after the fall of Meroë. Nubia bore many names, including Kush and Ethiopia in classical Greek.

Its people spoke in rich tongues, varieties of the Nubian language, echoes of which still linger in Nobiin and other dialects. Languages like the Birgid once floated in the air north of Nyala in Darfur but have since faded into silence.

Nubia's story is intricately woven with the rise and fall of kingdoms, cultures, and epochs. From Naqada's conquest of Ta-Seti to the protodynastic period, Nubia was a nexus of power, trade, and culture. A land once depopulated, it saw the return of its people, the ebb and flow of cultures like the A-Group and C-Group, and the dance of Saharan nomads with the aridity of the desert.

Trade thrived between Egypt and Nubia, gold and exotic riches flowed along the river's course, and small kingdoms blossomed and wilted. There were conflicts and expansions, as during the Egyptian Middle Kingdom, and interactions of distinct cultures, such as the Pan Grave and C-Group.

Nubia was not just a land but a living, breathing tapestry of human endeavor, art, war, trade, and faith. It was a corridor between Egypt and tropical Africa, a bridge across time, a symphony of civilizations that still resonates in the silent deserts and along the eternal flow of the Nile.

Trade thrived between Egypt and Nubia, gold and exotic riches flowing along the river's course, and small kingdoms blossomed and wilted. There were conflicts and expansions, as during the Egyptian Middle Kingdom, and interactions of distinct cultures such as the Pan Grave and C-Group.

Nubia was not just a land but a living, breathing tapestry of human endeavor, art, war, trade, and faith. It was a corridor between Egypt and tropical Africa, a bridge across time, a symphony of civilizations that still resonates in the silent deserts and along the eternal flow of the Nile.