The African Man Who Became Pharaoh of Ancient Egypt

I stand ankle-deep in hot sand as dusk settles over an ancient stretch of the Nile. In this land of the pharaohs, even the wind carries whispers of lost kings. Beneath a half-buried stone stele etched with faint hieroglyphs, I can almost hear a voice—a forgotten king calling out from three millennia ago. The air is thick with memory. A buried kingdom stirs awake under my witness.

Though I walk through this narrative as if I saw it myself, the story belongs to Piye. What follows is drawn entirely from a single, extraordinary source: the Victory Stela of Piye, inscribed by royal scribes in his name. It's not legend, but record—his words, his deeds, set in stone. I have merely stepped into the spaces between the lines to bring them to life.

With a cautious step, I brush sand off the carved granite—the name Piye glints in the last sunlight. Time peels away, and the desert around me begins to transform. Crumbling ruins rebuild themselves in my mind's eye. I am no mere observer; I am Rolo, the Witness of All Times, and tonight, the buried kingdom of Nubia rises from oblivion.

Nile Rivalries and the Rise of Kush

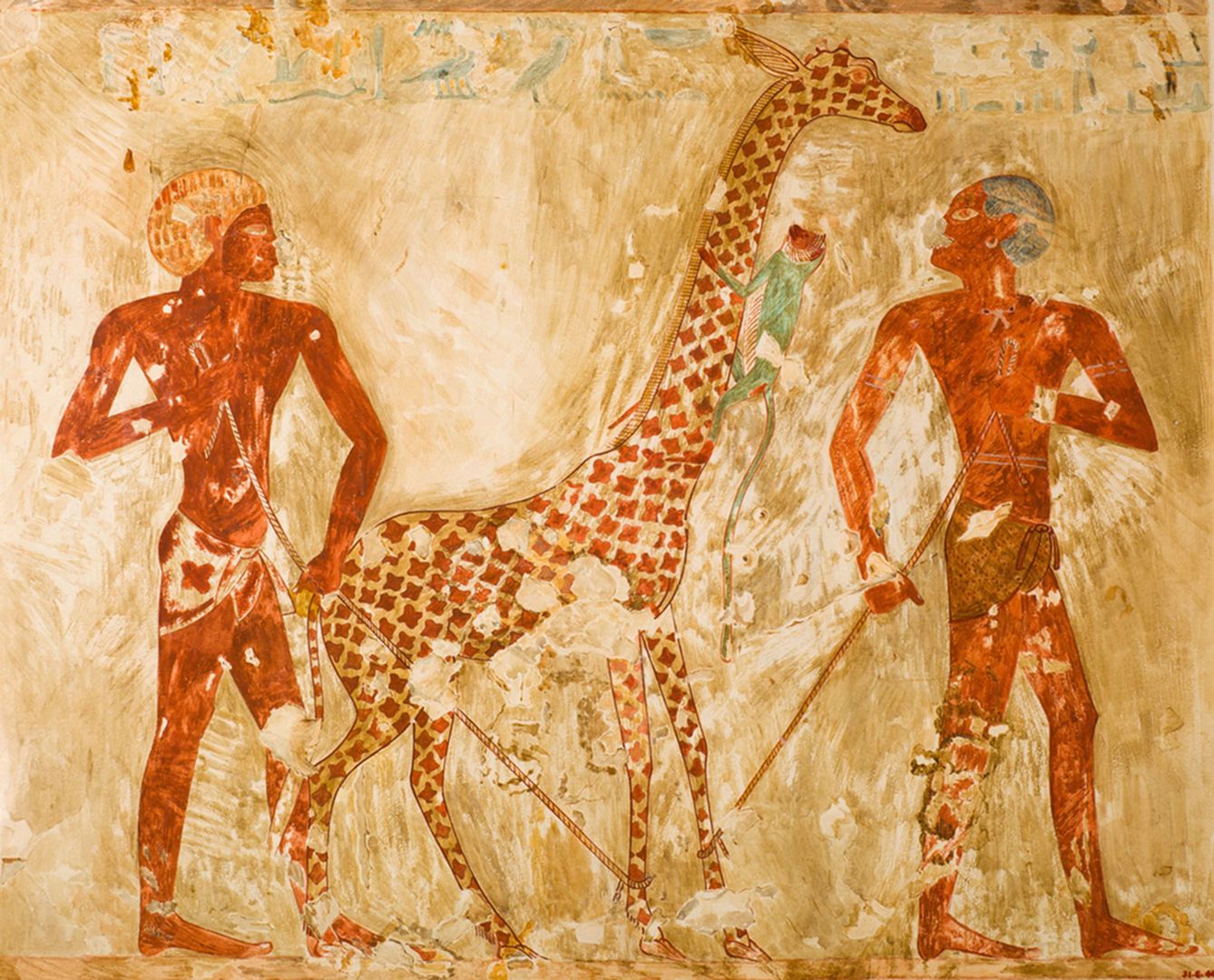

The scene sharpens into morning light, centuries ago. I find myself on a sandstone bluff overlooking two worlds on a collision course. To my south lies Nubia – the Kingdom of Kush – it stretches along the Nile's great bends from Aswan to the city of Meroë. To the north sprawls Egypt, fractured but still proud. On an ancient map of Egypt and Nubia, they appear as neighboring territories divided by a border, yet the sinuous Nile and a shared heritage bind them together. The land of Kush is rugged, lush, and rich. Its people, master archers, are famed as the "Land of the Bow" in Egyptian texts.

At the center of Kush towers Jebel Barkal, a red cliff that the Nubians deem sacred. At its base, Napata thrives as the royal capital, home to the temple of Amun. By the third and fourth cataracts of the Nile, Piye wears the crown of Kush. He is an African man, tall and sure, bearing the proud look of a lion. Though far from the traditional courts of Egypt, he carries within him a birthright entwined with the pharaohs —a devotion to Amun, the great god whom both the north and south revere.

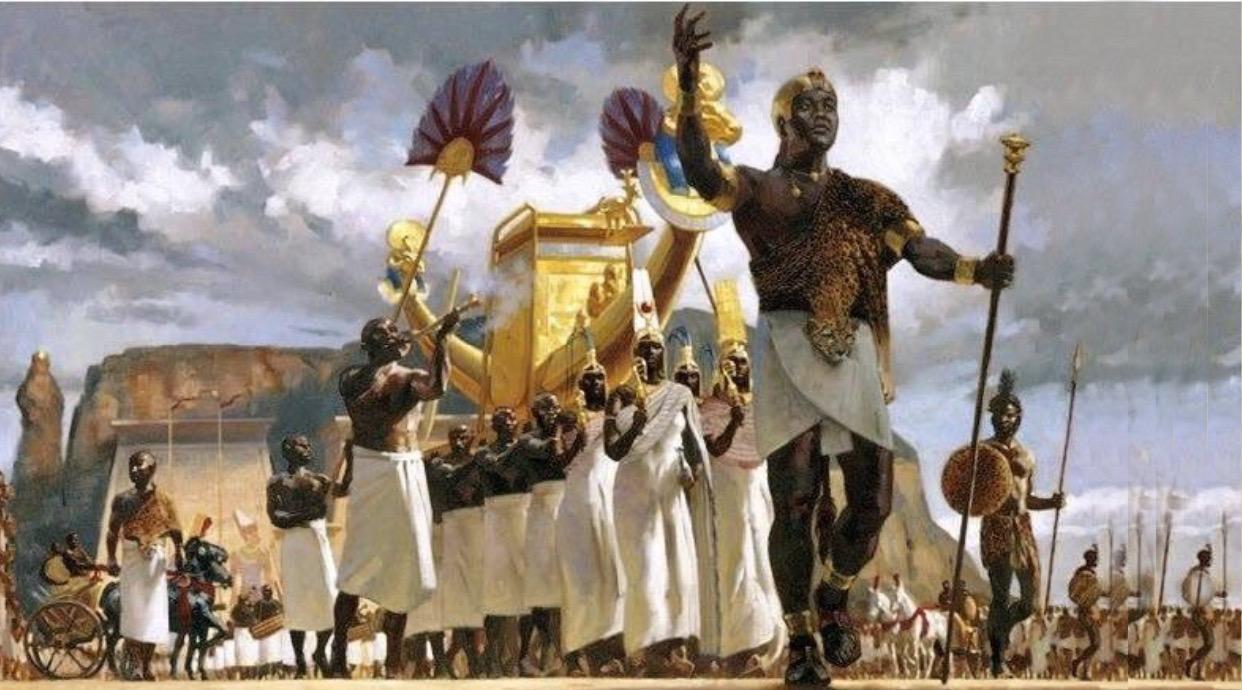

I blink, and suddenly, it's festival day at Jebel Barkal. The aroma of frankincense & myrrh sweetens the hot breeze. King Piye – garbed in linen and leopardskin – leads a procession through a jubilant crowd. They process toward the sandstone ram-headed sphinxes guarding Amun's temple while drums pound like a heartbeat. Here, Upper Egypt and Nubia meld; priests in white robes chant ancient hymns that vibrate off the cliff face. The sight of Piye pausing reverently before Amun's statue sends a hush through the crowd. At this moment, I see why his people trust him—Piye rules by the grace of the gods, with humility in the face of the divine. The Kingdom of Kush is rising, fueled by faith and a fierce sense of providence.

But beyond these celebratory sands, the world is unsettled. Up the Nile, Egypt is a broken mosaic. In Upper Egypt and Lower Egypt, petty warlords and princelings squabble over the remnants of a fading empire. I have heard rumors carried on the river that the delta to the north is ruled by Libyan chiefs wearing Pharaoh's titles without Pharaoh's unity. One such chieftain is Tefnakht of Sais, a cunning prince in the western delta. Even now, Tefnakht's ambitions creep southward like a dark stain on a map of Libya and Egypt. From my vantage, I imagine a "Libya map" spread out in his war tent – each conquered town highlighted with ink: Heracleopolis, Oxyrhynchus, Crocodilopolis – city after city falling under his sway. In Middle Egypt, fortress walls crumble without a fight. Some rulers, like the Prince Namlot of Hermopolis, have switched allegiance to save their skins. Others, like the lord of Heracleopolis, send desperate envoys pleading for Piye's protection.

In Thebes, the sacred city of Amun at the boundary of Piye's influence, anxiety hangs in the air. Tefnakht's advance threatens even Thebes – Amun's homeland in Upper Egypt. For Piye, this is more than geopolitics. It's personal and spiritual. An attack on Thebes is an affront to the god who legitimizes his rule. As the Great Chief of the West pushes toward Amun's domains, Piye hears the call to defend faith and kingdom. The forgotten king's story is about to unfold in war.

Rolo's Note: On the eve of battle, I turn to the Nile's endless night sky. Millions of ancient stars glint off the dark river – the same stars Piye himself must have watched. I feel both tiny and immense at the same time. Even after countless journeys, this sky river of starlight fills me with a profound sense of awe.

The Kushite March North

The first light of dawn creeps over the palms and mudbrick houses of Thebes. I stand in the cool shadow of Karnak's towering pylons as King Piye steps forward to kneel at the feet of a colossal ram-headed Amun. The temple is silent save for the crackle of torches and the murmur of priests. Piye presses his forehead to the temple floor, his lips moving in prayer. In this dim hall forested with lotus-topped columns, I sense the weight of his reverence. Here is a conqueror who seeks permission, not just victory. When Piye rises, he leaves lavish offerings – bread, beer, bulls garlanded with flowers – and in return, Thebes bestows on him its blessing for the campaign to come. With Amun's favor secured, the king of Kush is ready to march north and confront destiny.

Outside the temple, the city of Thebes awakens to the sight of a Nubian army assembling. Thousands of men with bronze-tipped spears and recurved bows gather by the river. Sunlight glints off their ostrich-feathered helmets and leather shields. At the front, chariots creak, and war horses stamp impatiently – Piye's beloved stallions snort and paw at the ground. I climb onto an outcrop to watch the moment. With a cry to Amun of Napata, Piye raises a bow to the sky. A wave of ululation breaks from his troops. They set forth a living river of warriors flowing north down the Nile.

The campaign begins swiftly. Weeks later, I find myself on the deck of a Kushite warship slicing through the Nile's currents. As our fleet pushes north, the Libyan flotilla suddenly appears ahead of us. Kushite archers let fly a cloud of arrows, and our warships crashed into the enemy boats with thunderous force. Timber splinters and water churns red – in minutes, the Libyan fleet lies in ruins. The surviving enemy sailors leap into the shallows and flee as smoke curls into the sky. The message is clear: Piye is coming, and not even the Nile itself will bar his path.

Piye's forces march overland into Middle Egypt. The heat is merciless; dust clings to sweat on every soldier's skin. I walk beside them through abandoned villages, where even the goats have been plundered by Tefnakht's foragers. Outside the walls of Heracleopolis, the next showdown looms. Tefnakht's armies had bypassed this city, but Piye refused to. He cannot leave an enemy stronghold at his back. The battle for Heracleopolis is fierce and short. I witness Kushite warriors storming the gates with battering rams as defenders rain arrows from mudbrick ramparts. Amid the chaos, Piye's men scale ladders onto the walls, horns sounding behind them. It's over almost as soon as it began – the Libyan garrison breaks and flees, leaving Heracleopolis to throw open its gates in surrender.

City after city submits. At each stop, Piye orders his troops to respect the temples and the innocent. This is a sacred campaign as much as a military one. When offerings to the gods are due, battle pauses while priests conduct rites. I watch in amazement as Piye detours to worship at each central temple – in Hermopolis, he honors Thoth, the scribe god, with fresh cattle offerings, and in Heliopolis, he purifies himself in the sun temple. He believes victory is hollow without the gods' grace.

The Kushite army enters city after city, greeted by cheering priests or terrified magistrates bearing keys to the gates. In the province of Oxyrhynchus, where Tefnakht's governor once strutted, Piye's banner now flies high. Every surrender swells his ranks with volunteers grateful to see the Libyan yoke cast off.

Rolo's Note: I stand in the dust of a captured temple courtyard, where Piye kneels to burn incense in thanks to the gods. The air is rich with the scent of myrrh and spilled wine from the victory feasts. Reverence radiates from this warrior-king. During conquest, he remains a servant of something higher. As I watch him pray, sword still at his side, I feel an overwhelming respect. Throughout my travels, I have rarely seen faith and duty so closely intertwined. It strikes me that Piye's true strength flows from his unwavering devotion. In the quiet glow of lamplight on carved stone gods, I too, bow my head.

The war is not yet won. Ahead lies Memphis, the ancient capital of Egypt – the city of white walls. Tefnakht himself isn't there (he has retreated to the swamps of the delta), but his remaining loyalists are making a stand. Memphis's fortifications appear as I approach with Piye's vanguard. massive sun-baked walls that have repelled invaders for centuries. The city beyond seethes with defenders and panicked citizens. It is here, on the threshold of Lower Egypt, that Piye faces his greatest challenge.

The Sacred Campaign and the Fall of Memphis

The siege of Memphis begins under a searing sun. Piye's army encircles the city in a ring of bristling javelines. Siege towers are dragged across the plains, and arrows hiss from the battlements in reply. For days, Memphis holds out, its defenders emboldened by the knowledge that no foreign king has ever taken this cradle of pharaohs by force. I scramble for cover as catapults on the walls launch rocks the size of melons onto the besiegers. The ground shudders with each impact. Still, Piye's warriors press on, filling the moat and battering the gates—at the dawn of the third day, a breakthrough – literally. A section of Memphis's wall, weakened perhaps by an old fissure or the flood season, gives way with a thunderous snap. With a triumphant roar, the Kushites surge through the breach.

Inside Memphis, chaos reigns. I weave through twisting alleys as Nubian soldiers clash with Delta warriors in the streets. A temple to Ptah goes up in flames on my left; on the right, women and children run for shelter behind statues of long-dead pharaohs. In the city's heart, Piye rides in his chariot and orders his warriors to spare anyone who surrenders, striking down only those who still resist. Even in the frenzy of battle, he seeks to limit bloodshed. At last, resistance collapses. Memphis – the white-walled city of the god Ptah – falls to the king of Kush.

A silence falls with the smoke. The surviving lords of Lower Egypt come out from hiding like wary jackals. One by one, the defeated Delta lords creep into Piye's camp to surrender. Namlot of Hermopolis, the turncoat, throws himself flat before Piye's tent. The Nubian king spares him with scarcely a glance. The treasures of the delta – gold vessels, fine linen, lapis lazuli – are carried in by the wagonload as a tribute to the Nubian conqueror. Among the humbled is even the last prince of the old Delta dynasty, bowing to the son of Kush.

Word is sent to Tefnakht, skulking far in the marshes. All is lost. Cornered by inevitability, the Libyan prince finally swears an oath of fealty to Piye, though he pointedly does so from afar, too proud (or afraid) to come in person. In a letter delivered to Piye, Tefnakht acknowledges the Nubian's supremacy and begs for mercy. Piye allows him to live, content that Amun's order has been restored. The campaign, both sacred and martial, has achieved its aim – Upper and Lower Egypt are united under a single lord once more, at least for now.

Rolo's Note: History has a mischievous way of flipping the script. For generations, Egyptian pharaohs inscribed boasts of triumph over Nubian "foreigners" on temple walls. Now, how ironic that an African man from Nubia came to rescue Egypt from itself. For those who today obsess over the race of ancient Egypt, there is an irony here – Egypt's salvation came from a king of Kush whom earlier pharaohs would have considered a foreigner. Power is transient and often wears an unexpected face. The statues of Tutankhamun and Ramesses here in Memphis look on impassively, as if to say, "In the end, even we needed help from the south."

As the smoke clears, Piye forgoes any coronation or plunder. Instead, he quietly enters Memphis's temple of Ptah to give thanks alongside the local priests. Only after these sacred rites does he turn his army back toward the south, his duty in Egypt fulfilled. The military of Kush, weighted with tribute and glory, marches back up the Nile the way it came.

A Kingdom's Twilight

Twilight in the Nubian desert finds me standing among the pyramids of Meroë, their sharp silhouettes cutting against a purple sky. These are not the giant pyramids of Giza but smaller, steep-sided tombs clustered in groups across the dunes. In the waning light, they cast long shadows like the memories of kings – including Piye – who rest beneath them. Unlike the broad pyramids of Egypt's Old Kingdom, the Nubian pyramids reach skyward at striking angles (often 70° or more), as if reaching for the heavens. Wind travels through their truncated peaks, and many of these monuments have had their tops cruelly blown off. As I run my hand along a weathered block, I feel the bite of ancient scars.

Piye returned to Nubia, never again to wear the crown in Memphis. His descendants would rule Egypt as the 25th Dynasty for nearly a century. It was a time of regeneration – they restored temples, revived ancient traditions, and even resumed building pyramids, a revival of ancient Egyptian pyramid construction on Kushite soil after centuries with none.

The Nubian reign over Egypt was bound to decay. By 656 BCE, relentless Assyrian invaders had pushed the Nubian pharaohs out of Egypt for good. Piye's heirs retreated to their southern strongholds, and the torch of Egyptian rule passed to new hands.

Yet the Kingdom of Kush lived on. Farther south at Meroë, a new royal city rose, and Kushite civilization continued to flourish. The culture developed its own art and writing (the Meroitic script) even as it preserved the worship of Amun and many pharaonic traditions. For centuries, Kush prospered – wealthy in ironworking, trade, and the power of its warriors – the cultural torch of Africa even as Egypt to the north fell under foreign rule.

The end, when it came, wasn't at the hands of the Egyptians or Assyrians. It was a rising African power to the south. In the 4th century CE, the armies of Aksum swept up the Nile and overran Meroë, extinguishing the Kingdom of Kush in fire and blood. By then, Piye's stories had already faded. Sand reclaimed the once-thriving cities. The pyramids of Nubia stood neglected, their tips eventually broken by time – and treasure hunters.

In the 19th century, long after Kush had fallen, outsiders rediscovered this "lost" kingdom. European explorers and adventurers were astonished to find pyramids scattered across the Sudanese desert. Some, sadly, saw them only as mines for gold. In 1834, an Italian treasure hunter named Giuseppe Ferlini blew the tops off several Meroë pyramids in a ruthless search for gold. He uncovered Queen Amanishakheto's jewels but at an appalling cost to Nubia's heritage.

Rolo's Note: I still remember the sorrow that settled in my heart that day in 1834. Standing among shattered stones and choking dust, I felt the weight of two and a half millennia crash down. What cruelty to see history broken for trinkets! The pyramids of Nubia, once gleaming monuments to a proud lineage, lay wounded by the very descendants of those who might have admired them. I knelt in the rubble of Queen Amanishakheto's tomb as Ferlini's men carted off her gold, and I silently wept for all that was lost. In my endless journey through time, few sights have pained me more than this – the willful robbery of memory, the memory of greatness drowned out by blasts of gunpowder.

But not all was lost. Scholars eventually translated Piye's Victory Stela, and archaeologists unearthed the story of the Nubian pharaohs at Napata and Meroë. Today, Meroë's pyramids are protected as a UNESCO World Heritage site, and Piye's story is taught as an integral part of Sudan's history. Now, he's not a simple footnote or a "forgotten king" – he is remembered as the first Nubian Pharaoh, the African ruler who once wore the double crown of the Two Lands and proved that the currents of the Nile ran both ways.

Rolo's Note: Piye’s brother Shabaka I feel a quiet reverence at the thought that a man from Kush once united the land of the pharaohs, led by faith and principle. His kingdom was buried, and his name nearly lost, but In the silence that follows, I know history has come alive and faded again. Yet I remain – the eternal witness – to carry this story onward.