Gerbil's, Jerboa's, Black Rats: The Plague Transporters

In February 2024, chaos erupted aboard an Airbus A330-300 en route from Pakistan to Sri Lanka when a single rat forced an emergency landing. The disruption delayed the aircraft for days, but this was far from an isolated incident. For decades, smuggled rodents have caused similar disruptions. In 2015, an Air India flight bound for London had to turn back after a rat was sighted, and in 2011, a Boeing 767 was grounded in Sydney when several rats were discovered just before passengers boarded. These events trace back to the earliest days of aviation.

While these drastic measures may seem extreme, the threat posed by rodents goes far beyond measly inconvenience. From smuggling attempts to historic pandemics, rodents have been tied to devastation on a global scale. But why? Despite many pets being allowed in cargo, rodents from the mammalian order Rodentia are rarely permitted on public transportation, mainly international flights. Strict regulations ensure that they are vaccinated, but against what, and for what reason?

Rodents have evolved to carry infectious diseases silently, often without showing symptoms. This immune tolerance has made them vectors for some of history’s deadliest outbreaks, including the infamous bubonic plague known as the Black Death. The underlying bacterial infection devastated populations during three pandemics. Even today, despite medical advances, rodents continue to harbor novel diseases. This is why they, like bats—creatures with similarly adaptive immune systems—remain banned from public transportation. The risk remains ever-present, from viral infections like COVID-19 carried by bats to bacterial infections like Yersinia Pestis carried by rodents.

Unlike viruses, which are not considered alive until they enter a host, bacteria like Y. pestis can thrive inside and outside the body. This bacterium created a deadly network of transmission involving fleas and rats, leading to widespread destruction. To combat the plague, leagues of rat catchers were once employed to exterminate rodents, and texts like the Ars Moriendi (The Art of Dying) were written to help people confront the terror of the disease.

In this post, we’ll explore the mechanisms behind the first and second plagues, the role of Yersinia pestis, and how fleas and rodents inadvertently conspired to alter the course of human history. Understanding this gloomy network could reveal the lingering dangers we still face today.

The Justinian Plague and A Bacteria

When discussing the plague, it's easy to overlook critical details due to the vast scope of the topic. However, one essential piece often missed is the Justinian Plague, or the First Plague (541-749 CE), long believed and now confirmed to have been caused by the same bacterial organism responsible for the more infamous Black Death.

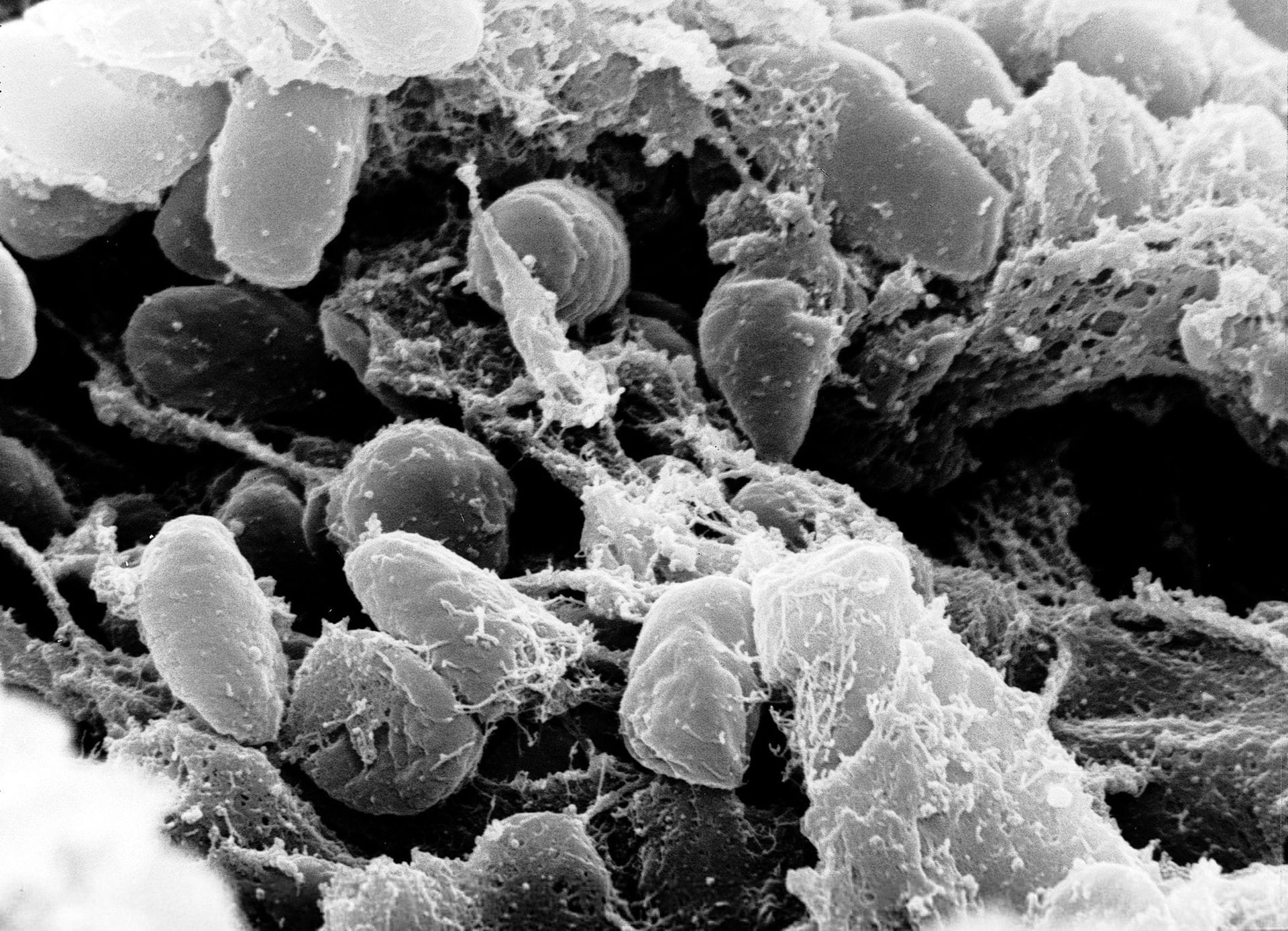

Before diving into the First Plague, let's first understand its underlying culprit: Yersinia pestis. Even among bacteria, Y. pestis

is remarkably small—short, plump, and distinct with its safety pin-like

appearance, encased in a protective 'slime' layer.

Many researchers believe this bacterium originated in Central Asia, specifically in the Tian Shan mountain range. In 2022, a team of scientists from Germany and the U.K. traced its genomes back to this natural border of China, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan, with a particular focus on Lake Issyk Kul in Kyrgyzstan, where their findings pointed firmly. Y.pestis is further traced back to somewhere between 5000 and 2000 BCE.

Three forms of plague infect humans: bubonic, pneumonic, and septicemic. These are progressive stages of the disease caused by Yersinia pestis, with

the mortality rate increasing at each stage.

We gain a clearer picture of the first wave of the plague through a chilling chronicle written in Syriac by a high bishop. Syriac is an ancient Middle Eastern dialect of Middle Aramaic and was used to document the outbreak. We'll also examine reports from Procopius, another prominent official of the same empire.

John, the Bishop of Ephesus, hailing from modern-day Turkey, served as a high priest under Justinian I, emperor of the Byzantine (Eastern Roman) Empire. Known for his discussions on the divinity of Jesus Christ, he authored the Ecclesiastical History. In the now-lost second part of this chronicle,

John detailed the devastating effects of the plague on its victims. This

account survives in an abbreviated form through another source, Michael the

Syrian, who referred to John as the 'John of Asia' instead of 'John, Bishop of

Ephesus.'

In his chronicle, John of Asia vividly recounts the devastating plague of 855 (543/4 CE), during the 16th year of Justinian's reign, describing it as unparalleled since the beginning of time. The scourge first struck the inland peoples of southeastern India, including Kush and Himyar, before relentlessly spreading westward to the Romans, Italians, Gauls, and Spaniards. Reports emerged of people going mad, attacking each other, and committing suicide in despair. The plague reached the borders of Kush, then swept through Egypt, cutting down its population like a scythe before ravaging Alexandria. Survivors were left with gruesome symptoms—groin tumors, swelling, and deep ulcers oozing blood and pus—leading to a swift and agonizing death.

John, Bishop of Ephesus, was a native of Amida (modern Diyarbakir, Turkey) in northern Mesopotamia and was in Palestine when the plague arrived, traveled from there to Constantinople, witnessing the plague conditions along the way, and was present in Constantinople during the plague there.

The Roman historian Procopius described the plague as an unequaled catastrophe that nearly wiped out humanity. He describes it as unlike any other terror, and this one defied all explanation. It struck indiscriminately—no land, season, or person was spared. Age, gender, or social status meant nothing; the plague moved with a silent, deadly intent. While some tried to speculate on its origins, no theory held, and only fear and despair remained in its path.

Procopius explains that the outbreak began in Pelusium, spreading swiftly west through Egypt reaching Alexandria, Palestine, and beyond. No coast, island, or mountain ridge escaped its grasp. It moved as if guided by a dark, deliberate purpose, even returning to lands it had previously spared. In Byzantium, people reported strange apparitions, and those who encountered them were soon struck down. Fever, madness, and swelling buboes stamped the doomed, and the air became thick with the stench of death as bodies filled every corner.

Subsequent outbreaks of the bubonic plague are scattered throughout historical records, especially some passages in the Syriac Chronicles. Two

notable accounts include the plague of 686 CE in northern Iraq, described by

John bar Penkaye, and the widespread outbreak of 743–745 CE, recorded in the Zuqnin Chronicle. These references offer further glimpses into the relentless return of the plague and its far-reaching impact on human civilization.

Procopius and John recall the outbreak starting with the Egyptians 'dwelling' in Pelusium, the Roman provincial capital. From there, it spread to the great Egyptian city of Alexandria and then traveled further, quickly reaching the ports of Gaza and Ashkelon. Both repeat the fact that the disease had no preferences, a non-discriminate killer that "embraced" the entire world as they saw it during the years of Justinian I.

John also observed that the plague's spread to Mediterranean countries such as Spain, Sicily, Italy, and Gaul was relatively slow. However, he noted that its pace accelerated significantly once he arrived in Constantinople with a small company from Syria. They noted evidence of the plague along the route as they traveled, finding it had already reached regions like Cilicia, Moesia, Iconium, and Asia. The disease was likely carried to these areas by travelers and traders, like John himself, who were moving from Syria and Palestine to Constantinople.

It's long been debated whether the Yersinia pestis bacterium caused the pandemic from 543 to 749 CE. However, the symptoms described by John of Ephesus, Procopius, and other travelers—particularly in the Chronicles of Seert/Syriac—align with what is now understood about the bubonic plague. Cysts formed on the head, knees, armpits, and groin.

Further concrete evidence came in 2014 when a team of scientists from the Center for Microbial Genetics and Genomics and the Department of Biological Sciences at Northern Arizona University studied the teeth of two cadavers that died during

those times, aged 98 and 62. Their findings confirmed the presence of Y. pestis.

Y. pestis has four main branches, with cases likely going undocumented as far back as 5,000 years ago, despite the bacteria ravaging communities during that period. These lineages are distinguished by how they evolved to infect their victims, primarily through fleas, which passed the bacteria to scurrying compatriots.

Because around 3300 BC, thousands of years before the first plague, a select few strains of Y. pestis took a significant evolutionary step. Some of its

lineages adapted to fleas, allowing the plague to spread across broader regions

and become zoonotic - transferable to humans by animals. The earliest known

evidence of plague in a human dates back to this prehistoric time frame on the

Iberian Peninsula, and it's likely the first evidence of an infected flea.

Rodents and The Flea

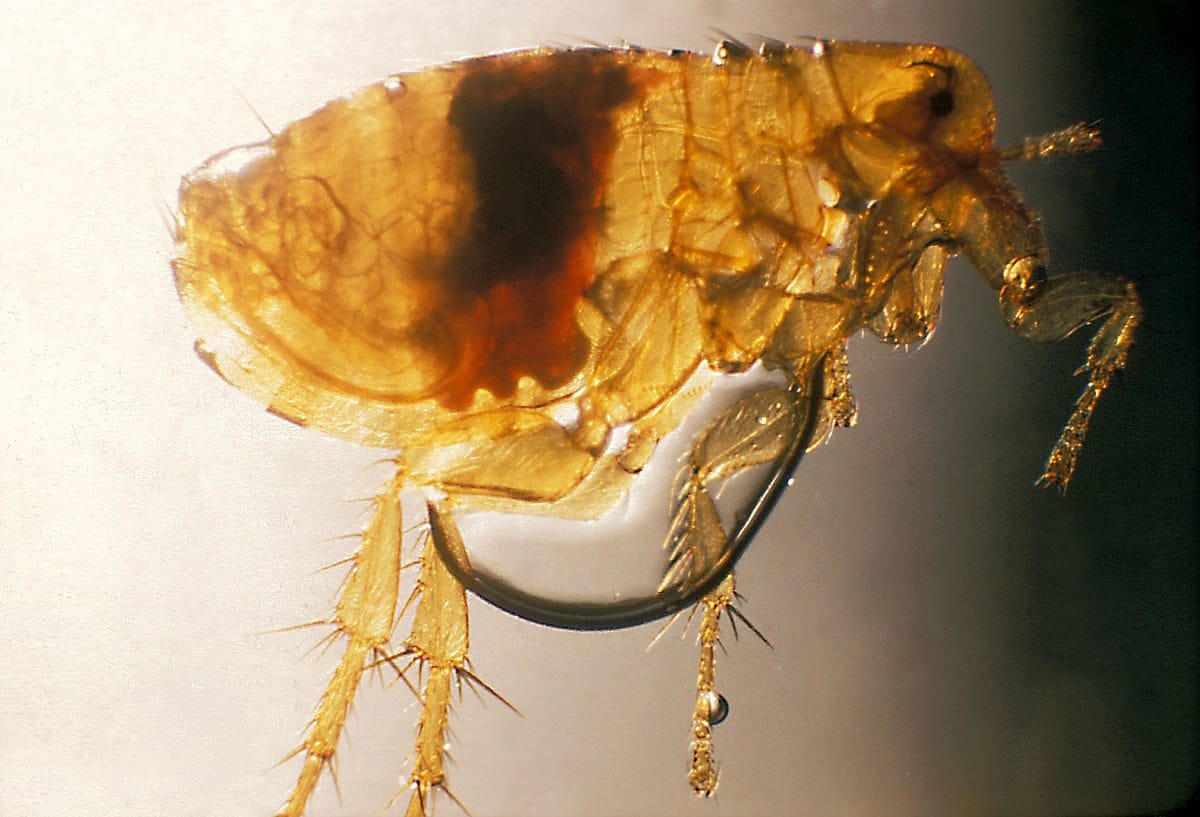

The flea in question, Xenopsylla cheopis, commonly known as the Oriental rat flea, is a tiny but deadly parasite. Though its bite may seem insignificant, it can transform the host into a carrier of the bubonic plague. These blood-sucking parasites can leap several feet into the air to reach their targets, burrowing through fur or hair to access the skin and feed.

Rat fleas possess rigid, backward-facing hairs that make them difficult to remove from fur and a tough, rubbery exoskeleton that makes them nearly impossible to crush. Their preferred habitat is the fur of rats and other rodents, where they remain hidden until it’s time to feed. Fleas typically live in the nests of their host animals, attaching to their hosts only when they need a meal but otherwise moving freely around the nest.

The Oriental rat flea was first identified in Egypt in 1903 by entomologist N.C. Rothschild and Karl Jordan. Today, this species can be found worldwide, wherever its preferred host—the rat—resides.

Most flea species, including X. cheopis, thrive in campsites and hiking trails, where they can detect warm-blooded prey, whether stationary or approaching. After leaping onto an animal, these fleas feed by sucking blood from a pool (telmophagy), unlike mosquitoes, which draw blood directly from vessels (solenophage). Fleas are especially prevalent in urban areas, where human habitats attract rats, such as city sewer systems and the undersides of trading ships. These fleas prefer tropical and subtropical climates and are rarely found in colder regions.

When X. cheopis becomes infected with Yersinia pestis, a dark, obstructive mass forms in the flea’s foregut, visible through its semi-transparent body; as the flea bites, it regurgitates blood mixed with this mass into the open wound, transmitting Y. pestis to its host. The fleas X.cheopis, already adept at hitchhiking, latch onto rodents from the vast order Rodentia, turning their travel into a deadly journey.

This infection cycle is likely what caused rats to spread the plague—just as we saw in Constantinople during the Justinian Plague.

However, there are still missing pieces regarding the disease’s pathway. We know the plague's spread began somewhere in Central Asia before reaching Arabia and Egypt, but the exact route remains uncertain. While black rats were found in Central Asia, they hadn’t spread significantly during the Justinian Plague.

As humans traveled along the Silk Road, passing through places like Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan, they were also likely carriers of the infection.

Among the rodents, three species stand out as potential contributors to the spread of the plague—though only black rats have been definitively linked. Due to their habitats and social behaviors, these rodent species likely played vital roles in forming a network of infection, starting with a family of little desert wanderers.

Jerboas and The Oases

Dipodidae, commonly known as jerboas, are a distinctive 'desert-hopping' species within the Rodentia order. Many subspecies include the Lesser and Greater Egyptian species, Five-toed, Three-toed, and several others. Jerboas are widespread across desert regions, often found near oases or valleys. They forage in open areas with sparse vegetation, allowing them to avoid competition with other rodents like gerbils, which prefer denser, more vegetated environments. This unique adaptation helps jerboas thrive in resource-limited areas where competition is reduced.

The Lesser Egyptian Jerboa is notable for its extensive range and fascinating physiology. These animals, resembling miniature kangaroos with their long hind legs and upright posture, inhabit regions from North Africa to the deserts of Arabia and Central Asia. They are prevalent in Egypt, with significant populations in Central Asia, stretching west to Morocco and as far south as Sudan—referred to earlier by its ancient name, Kush.

Jerboas are solitary animals equipped to travel long distances across the desert, often in search of food, providing them with water. Their ability to move swiftly through the dunes allows them to carry fleas over wide ranges, particularly to oases. These journeys frequently lead jerboas to settle in areas where they find their preferred vegetation diet, nuts, small insects, and fleas. It is expected to see them in oases that were once vital stops along the Silk Road, such as Merv in Turkmenistan, Bukhara in Uzbekistan, and the smaller oases of the Karakum Desert.

The Lesser Egyptian Jerboa's range is no coincidence. These regions—North Africa, Arabia, and Central Asia—were crucial points along the Silk Road, an essential global trade route even during the Justinian Plague. Merv and Bukhara, frequented by traders and caravans, were commercial hubs and potentially epicenters for spreading disease. The convergence of human and jerboa populations in these humid desert sanctuaries may have facilitated interactions between fleas and passing traders. While black rats were first recorded in the Siwa Oasis in 1758, likely due to urban and agricultural expansion, jerboas had been present in these areas for much longer.

In sediments from the early middle Miocene epoch, the oldest fossilized jerboas were found in Gansu Province, China (Young, 1927). The discovery of partially fused and elongated metatarsal bones indicates that jerboas evolved cursorial (running) features early on. The elongation of their hindlimbs and reduction in digit number is believed to be an adaptation for running bipedally at high speeds over great distances in search of food in arid climates. Studies have shown a correlation between jump length and habitat, with the most proficient leapers found in sparsely vegetated deserts (Berman, 1985).

Like those along the Silk Road, oases were vital checkpoints for travelers seeking rest during arduous journeys. These humid sanctuaries were prime foraging grounds for nocturnal jerboas, who emerged at night to feed on plants, seeds, and insects. While history often overlooks the role of jerboas in disease transmission, their interaction with traders and other animals in these regions could have contributed to the spread of the plague.

Although it has not been studied in detail whether jerboas interact with gerbils, another family within the order Rodentia, such interactions are likely. Both are nocturnal and while jerboas are solitary, desert gerbils tend to form colonies and dwell closer to human settlements.

Indian Gerbils

The Thar Desert, straddling the India-Pakistan border, covers over a million square kilometers. It is the most densely populated desert in the world, home to over 30 million inhabitants, mainly due to the presence of an ancient desert capital. Jaisalmer, an ancient trading city, lies in the heart of this desert in what is now the state of Rajasthan. Established nearly 1,000 years ago by a religious king named Rawal Jaisal, the city once served as a central trading hub between East and West Asia.

Traders and merchants built homes and temples as spices, silks, and other luxuries flowed through this desert post. Alongside them, pests of the Thar Desert, particularly gerbils, also made their home in and around the city.

Meriones hurrianae, or Indian gerbils, are a species of rodent distributed across Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and the Indian desert. They are closely related in appearance to dwarf hamsters but with hairless, rat-like tails. Indian gerbils are incredibly fast burrowers—faster than jerboas—and this skill helps them avoid predators like snakes. These rodents thrive in various habitats, making them the most abundant rodent species in the Thar Desert.

A significant study conducted by biologists Ishwar Prakash and Soroj Kumari in 1981 confirmed that Indian gerbils are solitary, but unlike jerboas, they live in social groups. In confined areas containing multiple burrows, there is usually only one dominant male and one dominant female.

The gerbils prefer sandy plains, particularly near bushes, and rarely stray far from the hummocks unless it rains and the shifting dunes stabilize. In Bikaner, a city not far from Jaisalmer, gerbil burrows have been observed to cluster around the hummocks. This behavior offers them an advantage, particularly in the hot summer months. The extensive root systems of the bushes around their burrows help maintain higher soil humidity, enabling the gerbils to withstand extreme desert temperatures.

In the past, these desert gerbils were as prolific in the district before the canalization of the region as they are now in other sandy plains of Rajasthan (Prakash, 1958). However, their numbers have been drastically reduced due to modern land use practices. Today, M. hurrianae is found near crop fields on uplands where patches of sandy soil remain.

In ruderal habitats, particularly near human settlements, they are often seen in the mud-thorn fences of dhani (desert homes) and cattle sheds. While Indian gerbils do not typically enter houses, which are now predominantly inhabited by black rats, they remain close to human activity. Whether they thrive solely on natural vegetation or rely on humans for food remains unclear, but their proximity to settlements suggests some level of dependence and interaction.

The Sewer Rat and The Ship

Rattus rattus, commonly known as black rats, ship rats, roof rats, or house rats, are unique among many other rodents in Rodentia's order due to their global distribution. They have impacted numerous ecosystems by destroying crops and invading new areas. Unlike jerboas and gerbils—rodents that likely carried Xenopsylla cheopis (the flea responsible for spreading the plague)—black rats are far more commensal and adept climbers. While jerboas and gerbils tend to avoid human habitats, R. rattus thrives in them. Commensal rodents live close to humans, where they can easily find food, water, shelter, and space. Black rats are one of the primary rodent species categorized as commensal.

Their lineage shows how effectively they have spread across the globe, primarily through maritime travel. DNA analysis has revealed ten distinct subtypes of black rats, each having spread to different regions over time. Type 1 is the most widespread, having reached every continent. In contrast, Type 2, the second most pervasive, is primarily found in southern Asia, from Vietnam and Malaysia to Papua New Guinea and Australia, covering over 5,000 kilometers.

Type 1, however, originated in southern Africa and spread far beyond, tracing the routes of early global trade. This subtype is strongly linked to the dissemination of the Black Death due to its association with international shipping routes. R. rattus is a medium-sized rodent with a long tail that aids it in climbing, making it particularly suited to urban areas and ships where food is plentiful. After the rise of European maritime trade, particularly with companies like the Genoese Merchant Fleet, black rats began migrating from Southeast India, stowing away on ships and spreading across continents. Their expansion became synonymous with the Age of Sail.

One of the more lesser-known instances of rats aboard ships was their presence on the Titanic, the British passenger liner that sank in the Atlantic on April 15, 1912. Like those on other vessels, these rats would have boarded the Titanic by climbing the unguarded mooring lines when the ship was docked.

A surviving fireman named Jack Podesta recounted a vivid memory of rats aboard the ship during an interview with Southern Evening Echo in 1968. He stated, "That morning, my friend and I were standing by a watertight door when we suddenly saw six or seven rats running toward us from the Titanic's starboard side. They passed by our feet, and we kicked at them as they ran off. We didn't think much of it at the time since rats are common on ships, but looking back, I believe they could sense danger."

Another fireman aboard the Titanic, Thomas Ranger, testified at the British Board of Trade inquiry into the sinking on May 9, 1912. He described the crew's quarters as filthy and rat-infested, so much so that he preferred to sleep outside most nights. This level of infestation was not uncommon for RMS ships at the time.

While there are no precise records of the number of rats aboard the Titanic, surviving eyewitnesses collectively reported seeing dozens. Some children aboard even chased after them. Around this same time, a law was enacted requiring rat-guards on mooring lines to prevent infestations.

While black rats were notorious stowaways on ships, their influence extended well beyond the maritime world and into the very sewers of burgeoning urban centers. As these rats disembarked at ports across Europe, Asia, and Africa, they quickly adapted to new environments and spread rapidly. Their migration mirrored the rise of international maritime commerce and the networks established by European powers eager to exploit new trade routes. Therefore, the black rat's journey is deeply intertwined with the growth of maritime empires.

In urban settings, black rats thrived in the expansive sewer systems. Personal accounts from sewer workers in Britain, known as "toshers," describe harrowing encounters with swarms of rats. Toshers scavenged for valuables in the sewers, often forced to defend themselves against rats that would attack in packs if they felt cornered. A well-known tosher, Tom Wilks, carried a stick specifically for fending off these rodents. In his journal, Wilks described how rats thrived in the warm, damp environments of the sewers, feeding on food waste and human excrement, growing to remarkable sizes.

This rat problem was global. Similar stories from Russia, Japan, France, the United States, and across the European Union echoed the same concerns—rats infesting underground sewer systems and posing significant public health threats.

The threat posed by R. rattus was not only historical but remains relevant today, as evidenced by modern-day incidents like the Airbus emergency landing in 2024, where a single rat forced the plane to divert. This continued presence of rats in human transportation and urban areas reflects a lingering global issue.

The bones of Rattus rattus have been uncovered in zooarchaeological sites throughout the Mediterranean Basin dating back to the early Middle Ages (1100–1300 CE), with notable finds in Palestine, Su Guana (Italy), and Galera (Spain), among others. These discoveries further prove their widespread presence and their role in spreading disease.

Now, I'll conclude with a fictional story inspired by these insights, illustrating how a bacterium from Central Asia could have traveled unnoticed along the Silk Road, through ports and sewer systems, aided by all three rodent families in the order Rodentia.

A Fictional Story and My Concluding Thoughts

In the mid-14th century, a caravan of traders departs from the desolate steppes of Central Asia, oblivious to the silent horror nestled among them. Laden with silks, spices, and treasures destined for the Arabian Peninsula, their actual cargo is a plague—a dark passenger riding the wind, hidden within the folds of their journey. It begins innocuously enough: a flea, Xenopsylla cheopis, clinging to the clothing of a weary merchant, carries the deadly microbes of Yersinia pestis.

The flea had gorged on a plague-ridden rodent in Central Asia's cold, barren heights, where the desolation itself seems to breed death. Here, in the shadows of jagged peaks and endless plains, the first seeds of the Black Death stir in secret, carried by fleas that flit like specters through the steps, their long limbs propelling them across the cracked earth. Oblivious to the doom they help spread, these traders make up the caravan.

As the caravan travels southward, the air grows heavy with an unseen tension. The flea, hidden in the traveler's bedding, clings to life, its eggs scattered in the thin cracks of the merchants' worn fabrics. The cool desert air offers little comfort, but something dark stirs whie the eggs lie dormant, biding their time.

The journey is long and unforgiving, the land mirroring the harsh fate awaiting the travelers. After days of ceaseless movement, the caravan halts at a secluded oasis. The traders, their bodies weary and their minds dulled by the heat, think nothing of the jerboas still darting at the fringes. They rest under the illusion of safety, unaware of what festers within their ranks. Beneath their feet, in the oasis's still waters and soft sands, the heat and moisture provide a fertile ground for the flea's eggs.

Time passes, but the death creeping through the caravan is patient. In the sweltering warmth of the oasis, the flea eggs hatch, larvae wriggling to life, feeding on the filth and residue of the human camp. They grow in silence, unnoticed, spinning cocoons within the folds of blankets and in the dark corners of the travelers' belongings.

The first man falls ill after the caravan departs from the oasis. At first, it's a fever—a simple thing in the desert heat—but then, the swellings appear. Dark, swollen lymph nodes rise like cursed tumors under his arms, near his groin. The others notice but say nothing, pushing forward through the desert's cruel expanse. They do not yet understand that brutal illness has latched onto their caravan, sinking its claws into the flesh of their companions.

By the time they reach the next resting place, the fleas have begun to emerge. The vibrations of footsteps, the warmth of the travelers' bodies, and the smell of sweat awaken the sleeping pests. From within the folds of blankets, from the dirt-laden hides of camels, the fleas spring forth, ravenous. They feed, some from those still healthy, but others from the infected—becoming the perfect harbingers of the plague.

Further south, in the heart of the Thar Desert, the caravan pauses again. The travelers, unaware that death now walks among them, collapse by a dry streambed to rest. It is here that the gerbils come, their homes nestled among the thorny bushes and sands that surround the campsite. Like the jerboas before them, the warm-blooded gerbils attract the ever-watchful fleas who wait, ready to leap from the infected host.

The fleas spread their infection swiftly, drawing blood and passing along the death knell of Yersinia pestis. The once-strong merchants begin to falter, their bodies ravaged by fever, their minds clouded by the pain of the swelling buboes. But still, they move forward, dragging themselves deeper into the desert, unaware that they have become vessels for the plague's next phase - widespread.

As the caravan reaches the Arabian Peninsula, the disease begins to burn through the remaining travelers, contaminating them with brutal efficiency. Yet, the fleas are tireless. Those that survive this leg of the journey leap onto new hosts: the black rats that scuttle through the shadows of the coastal ports. The ships anchored in the harbor, bound for distant lands, become the successive carriers of this invisible, unrelenting enemy.

The rats take the fleas into the underbellies of the ships, where the air is damp and thick, where the darkness is complete. In the dimly lit holds of merchant vessels, the plague thrives again, spreading far beyond the deserts through global trade. The Silk Road, both land and sea, is transforming from a path of wealth and prosperity to a road of loss and misery. But the germ will continue winding its way through continents and oceans, leaving devastation in its wake.

The black rats, far more cunning and adaptable than their desert cousins, carry the disease across seas and into port cities teeming with life. Unseen, they spread through sewer systems, marketplaces, and homes. Where the caravan once traversed barren landscapes, the ships now carve paths across the ocean, carrying Y. pestis and its ladder system to the world's farthest reaches.

From the high plains of Central Asia to the crowded streets of European ports, the plague becomes a chain of contagion—a natural disaster hidden in the fur of rodents, carried by the bloodthirsty fleas, infected by deadly bacterium. The merchants, the traders, and the sailors, all unaware, carry death with them wherever they go. And beneath it all, from the shadows of desert oases to the dark holds of ships, the fleas continue their work, and the rodents continue to adapt.

Though today we are more aware of the dangers these creatures pose, the reality remains: rodents, from jerboas to black rats, have adapted alongside the parasites they carry. The order Rodentia, with its vast and diverse cast of members, continues to live among us—often in close quarters. Their intelligence and adaptability make them both fascinating and formidable and while the stride of progress in modern medicine have given us powerful tools to combat such diseases, the intricate relationship between rodents, fleas, and pathogens persists.

It is true that advances in technology have lessened the threat of pandemics on such a devastating scale, but the adaptability of rodents is a reminder that nature's capacity for survival can never be entirely discounted.