The Rise And Fall Of Empires On The Grasslands Of Asia

In the endless sea of grass that is the Eurasian Steppe, under the eternal blue sky of the all-encompassing Asian god Tengri, great nations have risen on horseback and vanished like mirages. Among them was the Ashina clan, a once-obscure tribe of skilled blacksmiths who forged not only iron, but the first Turkic Empire. Their historical story, intertwined with myth, spans the fall of older nomadic overlords, the rise of mighty Khaganates, and the transformation of Central Asia from shamanic steppe realms to Islamic sultanates. It even reverberates in far-off lands where steppe-born warriors became the defenders of foreign kingdoms. This post chronicles the journey of the Ashina and their successors in a narrative that blends legend with scholarly insight – from the smoke of their forge fires in Altai mountains to the thunder of Mamluk cavalry on Egyptian sands.

The Ashina Tribe

According to legend, the origins of the Ashina are traced to a tale as old as the steppe itself. In this myth, a young boy who survived a massacre of his people is rescued and nursed back to health by a she-wolf in the wilderness. The wolf bore the boy a lineage of ten half-wolf sons. One of these became Ashina, the founding patriarch of the clan. The name Ashina is said to mean “blue” in an ancient tongue – perhaps a nod to the “blue wolf” totem or the endless blue sky that the nomads worshipped. A people destined to rule sprang from this mystical union of wolf and human.

Such fireside stories gave the Ashina a mythic aura. Around the tribal hearths within round felt tents (yurts), bards would recount how the Sky God Tengri watched over Ashina’s descendants. These nomads saw themselves as children of the sky and wind – fierce and free like the wolves coursing over the plains. Yet, the Ashina legend also carried a practical symbol: iron. The early Ashina, legend says, settled in the Altai Mountains, a region rich in ore, where they became master blacksmiths. In an age when empires were built on bronze and iron, this clan’s skill at metallurgy set them apart. Iron-weapoms, tools, and adornments crafted by Ashina smiths were prized across the steppe. One can imagine Ashina metalworkers stoking their furnaces in mountain forges, the sparks flying like stars as they hammered glowing metal on their anvils. The ringing of iron became the forge-beat of an empire in the making.

This dual image of the Ashina – wolf-blooded warriors and gifted blacksmiths – straddles the line between myth and reality. It gave later generations a sense of divine mandate and practical prowess. In truth, the steppe bred tough survivors. By the 5th century CE, Ashina tribespeople were serving a mighty overlord, using their iron craft in exchange for protection. They were not yet masters of their fate. That would soon change, but not before a dramatic clash that would catapult the Ashina from vassals to victorious conquerors.

From Tribe to Clan - Ashina Under Rouran

Before the Ashina ruled anything, the Rouran Khaganate dominated the Mongolian steppe (late 4th – mid 6th century CE). The Rouran were fierce nomads who styled their chief as Khagan (Khan of Khans) – one of the first uses of that exalted title. They held sway over a patchwork of tribes, including the Ashina. In 460, Chinese chronicles say the Rouran conquered the Ashina's homeland around modern Turpan and forcibly resettled the clan to the Altai Mountains. If the legend is to be believed, the wolves of Altai gained some new human packmates that year. The Ashina became known as 'metallurgists par excellence in these mountains, rich in iron.' Some scholars think the Rouran used the Ashina as iron smelters and blacksmith enslaved people, crafting weapons for the Khaganate's armies. This status was both a symbol of pride (for their skill) and one of subjugation.

By around 501CE, the Ashina chieftain was named Bumin (also recorded as Tumen). Bumin was an ambitious leader who chafed under Rouran's overlordship. He had thousands of horsemen at his command, likely because he'd united several tribes (including the Ashina-led Turkic people referred to as Tujue in Chinese records). The Rouran Khaganate, though powerful, was growing complacent, ruling over restive vassals like the Ashina and dealing with external rivals. Sensing opportunity, Bumin struck a careful balance: outwardly, he served the Rouran loyally but built his strength. In 545 CE, Bumin even established friendly ties with the adversary of the Khaganate, the Western Wei (a Chinese kingdom), likely to secure his flank if needed.

Well, that moment came in 546 CE, when a rebellion by tribes known as the Tiele shook the Rouran realm. Bumin swooped in to crush this revolt on behalf of the Rouran Khagan. His cavalry, hardened by years of frontier skirmishes, made quick work of the rebels – a tremendous victory that increased Bumin's prestige. Flushed with success, Bumin decided it was time for the Ashina to receive their due respect. He sent a message to Anagui, the Rouran Khagan, demanding a Rouran princess's hand in marriage. In steppe diplomacy, asking for a royal bride was bold – it signaled that Bumin saw himself as an equal, not a servant.

Anagui's reply was a grave insult: "You are my blacksmith slave. How dare you utter these words?" The Rouran ruler sneered at the Ashina's smithing heritage, calling Bumin a lowly servant unworthy of kinship. To a proud steppe warrior, this was the ultimate provocation. Bumin's response was swift and final – he executed the Rouran envoy who delivered the insult and broke all ties with the Khaganate. The smith's hammer was now forging a sword, not to be given but turned against his overlords.

In 552 CE, Bumin led his warriors in open revolt. The Ashina banner – emblazoned perhaps with a wolf's head or a mountain goat tamga – was raised in defiance of Rouran tyranny. The following battles were epic: hordes of Turkic horsemen, armor glittering with horse-tail decor whipping in the wind, charged at the Rouran hosts. Remember that by this time, Bumin had also allied with the Western Wei, even securing a Chinese princess as a bride to legitimize his new status. With allied support, his forces met the Rouran in combat north of the Altai and Mongolia. The once-mighty Rouran Khaganate fell in a cascade of defeats. Legend has it that Khagan Anagui, upon realizing all was lost, took his own life – ending the Rouran reign for good.

Amid the victory celebrations on the steppe, Bumin proclaimed himself "Illig Qaghan" – meaning supreme ruler of the Turks. A new empire, the Göktürk Khaganate (First Turkic Khaganate), was born. It was as if a spark had ignited a steppe wildfire – the small Ashina tribe suddenly blazed into an empire spanning from the Gobi Desert to the Caspian Sea. The year 552 marked when a "blacksmith slave" remade himself into a sovereign of all Turkic tribes. The forger of iron had forged a nation.

Interestingly, the fall of the Rouran also caused distant ripples: some defeated Rouran people fled west, possibly becoming the mysterious Avars who appeared in Europe soon after. One empire's collapse set off a chain reaction – a pattern seen often in steppe history.

The First Turkic Khaganate And It's Strategic Divide

Under Bumin’s successors, the Ashina-guided Göktürk Empire (often called the Celestial Turk Empire) reached astonishing heights. Upon Bumin Qaghan’s death (he lived only a few months after founding the empire), leadership passed to his clan. His brother İstemi took over the western tribes, while Bumin’s sons ruled the eastern heartland. The empire split into an eastern and western wing, each governed by an Ashina royal but united in loyalty to the Ashina family. This clever power-sharing mirrored the vastness of their realm – a nomadic superpower straddling Central Asia.

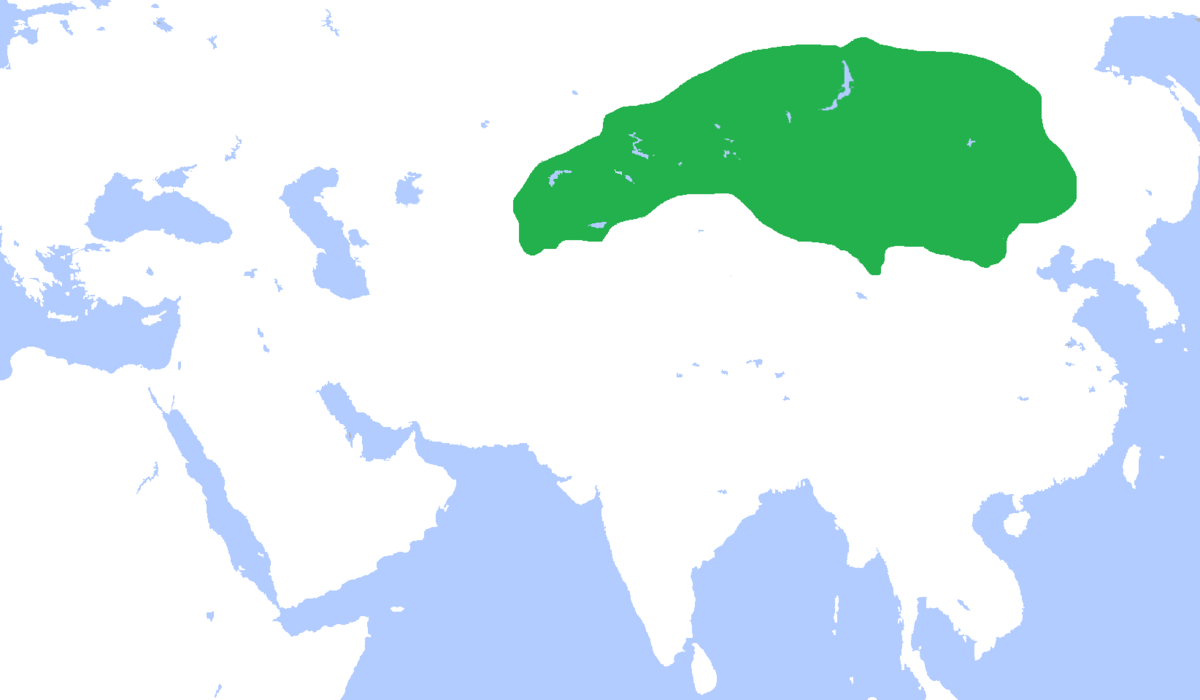

At its peak, the Göktürk Khaganate controlled the old lands of the Rouran and more. From Manchuria and Mongolia in the East to the Black Sea steppes in the West, the Turks held sway over a multicultural empire of nomadic tribes and settled trade cities. To the sedentary civilizations of China, Persia, and Byzantium, they were now the paramount power of the steppes. The Ashina clan, once hidden in the Altai, was now negotiating with emperors and shahs as equals.

Life in the Göktürk Empire was still quintessentially nomadic at its core. The Ashina khagans maintained royal camps at sacred sites like Ötüken (the legendary royal forest in Mongolia believed to be the seat of divine power for Turkic rulers). They moved with the seasons, grazing their innumerable herds of horses, sheep, and cattle on summer highlands and winter pastures. The empire’s wealth rode on the hoof – fine war horses, shaggy oxen, and flocks of hardy steppe sheep. Yet their dominance also rested on their iron weaponry and superb archery, products of that blacksmith tradition they carried. Göktürk mounted warriors were a fearsome sight: clad in lamellar armor of iron scales or hardened leather, armed with the recurved composite bow that could punch arrows through armor at full gallop.

They could live for days in the saddle, moving faster than any army of footmen. In battle, Turkic cavalry used lightning hit-and-run tactics, encircling enemies in clouds of dust and arrows. Settled kingdoms learned to fear the sight of these “blue Turks” (as Göktürk translates) sweeping in from the horizon, as unstoppable as a storm.

Politically, the Ashina rulers showed shrewdness in governance and diplomacy. They often married princesses from China or Persia to cement alliances. The Göktürks also patronized merchants: they sat astride the Silk Road routes, and İstemi in the West dealt astutely with Sogdian traders. It was said that silk from China, gold and glass from Byzantium, and spices from India all traveled under the protection of the Turkic Khans. İstemi Qaghan famously allied with the Byzantine Empire against their common enemy, the Sassanid Persians, to open trade.

This east-west diplomacy was revolutionary – for the first time, a steppe power was engaging in global geopolitics, linking the Eastern and Western world. A Turkic embassy even visited Constantinople in the 6th century, astonishing the Romans with their exotic furs and braided hair and proposing joint military operations. The Ashina Khagans understood that to rule the steppe. One must also manage relations with the neighboring “civilized” realms – as both threat and trade partner.

Culturally, the Göktürk elite practiced Tengrism, worshipping the Sky God and the spirits of ancestors and the natural world. Shamans wielding drums and clad in animal skins performed rituals for protection and victory. Nonetheless, the empire was religiously eclectic: through their Sogdian intermediaries, Turkic Khans became acquainted with Buddhism, Nestorian Christianity, and Zoroastrianism. Some Göktürk princesses were said to favor Buddhism and had temples built. The Ashina clan appeared to tolerate a mosaic of beliefs as long as loyalty was maintained.

The Göktürk Empire was at once mobile and monumental. It left few cities (nomads did not much need them), but it did leave behind remarkable stone monuments. Outside a lonely bend of the Orkhon River in Mongolia, two remarkable inscribed steles still testify to this golden age. Erected in the early 8th century, the Orkhon Inscriptions (written in Old Turkic runes) recount the saga of the Ashina rulers with proud, poetic words. They praise the wisdom of the Khagans and also serve as cautionary tales.

One passage, attributed to an Ashina prince, addresses the Turkic people: “Because of the Chinese riches and clever tricks, the Turkic nobles were beguiled, and our nation was brought to ruin… But thanks to Heaven (Tengri) and our mighty Khagan, we rose again.” This refers to a pivotal episode we will soon explore – a time of collapse and revival. The inscription essentially warns: do not forsake your nomad way of life and unity, or you will fall prey to foreign powers. It is a powerful reminder of how the Ashina viewed their mandate: to keep the nation strong, free, and true to its roots.

The stones even invoke the hardship of losing independence: "Oh my people, remember how you hungered and thirsted when you had no khan of your own.” Carved deeply into the rock. These words have endured twelve centuries of wind and winter on the steppe, just as the story of Ashina endures in history.

The First Turkic Khaganate And It's Disastrous Collapse

By the end of the 6th century, despite its power, the Göktürk Khaganate began to fracture from within. The empire was vast and stretched thin, and rival claimants of the Ashina family quarreled over succession. After the great early Khagans (Bumin, İstemi, and the capable Muqan Qaghan), weaker, greedier rulers came to power. Different factions of the Ashina and allied tribes broke the unity that had made them strong. The western and eastern wings of the empire grew distant and sometimes hostile to each other. Local tribal leaders (begs and lesser khans) started acting autonomously. Essentially, the Göktürk Empire’s bright summer entered an autumn of discord, and enemies took notice.

In China, the newly established Tang Dynasty (from 618 CE) eyed the divisions among the Turks as an opportunity. The Tang emperors, ruling a revitalized and confident China, practiced a savvy mix of warfare and diplomacy to undermine the Ashina power. They nurtured discontented Turkic princes, supported rebel tribes, and struck militarily when the time was ripe. In 630 CE, the Tang launched a significant campaign against the Eastern Göktürk Khaganate. Led by General Li Jing, Tang armies (including allied Turkic troops who had switched sides) defeated the main Göktürk forces and even captured the Khagan, Illig Qaghan (an Ashina royal). It was a crushing blow. Thousands of Turkic clansmen were taken prisoner and resettled inside China’s borders. The proud sons of the steppe now found themselves paraded in submission at the imperial court in Chang’an.

With this, the Eastern Turkic Khaganate was effectively dissolved. Chinese historians record that the Tang emperor Taizong even took the title “Heavenly Khan” to signify his authority over the steppe – a symbolic gesture that many Turkic nobles begrudgingly acknowledged. The Western Göktürk realm lingered longer but was beset by internal strife and encroaching enemies. By the 650s, Tang China extended its influence to the Far West, and in 657 CE, a Tang general defeated the last significant Western Turkic Khans. The great empire of the Ashina had splintered like a once-strong sword, now broken by internal cracks and external hammer blows.

For a time (the mid-7th century), the steppes had no dominant khagan. The Turkic people acutely felt this interlude of disunity and foreign domination. Many were now living under Chinese governors or as mercenaries and vassals of the Tang. Others fled west into the domains of Persia or joined kindred tribes like the Khazars on the Caspian steppe. (Some historians believe an offshoot of the Ashina may have helped lead the Khazar Khaganate – a Turkic state west of the Eurasian steppe – demonstrating how the embers of Ashina power continued to glow in various places.)

Yet, the Ashina lineage was not extinguished. In their homeland, resentment smoldered against Chinese rule. As the Tang dynasty’s grip slightly weakened due to its overreach, Turkic patriots saw a chance to reclaim their independence. Like grass that regrows after a wildfire, the steppe would soon see a resurgence of Turkic power.

Enter The Second Turkic Khaganate

In 682 CE, a charismatic Ashina prince named Kutlug (given title Ilterish Qaghan, meaning “State Rebuilder”) rallied the remaining Turkic tribes in Mongolia and revolted against the Tang. Aided by his loyal general and wise counselor Tonyukuk (a grey-haired strategist who remembered both the glory and folly of the earlier days), Kutlug defeated the Chinese garrisons and reassembled a Turkic state in the old heartland. This was the birth of the Second Turkic Khaganate, essentially a restoration of Ashina rule on the steppe. It was as if a long-dormant seed had sprung back to life after a harsh winter, nourished by the desire for freedom.

Ilterish Kutlug died young after securing the basics of the realm, but he left the revived empire to capable hands – his brother Qapaghan Qaghan and later his son Bilge Qaghan (with the formidable Tonyukuk continuing as advisor). The Second Khaganate, though smaller in extent than the first, reasserted Turkic dominance in the core steppe (Mongolia and parts of Central Asia). Qapaghan was a harsh ruler, known for sternly subjugating any tribes that resisted re-unification. He expanded the khaganate’s influence over the steppe peoples from the Altai to the Tian Shan. However, his iron-fisted approach bred some resentment and he was killed in an ambush in 716.

It was Bilge Qaghan (716–734) who truly stabilized the revived empire. Bilge, whose name means “Wise”, proved to be just that. Along with his brother, the heroic general Kul Tegin, he maintained unity and fought off incursions by the Tang and others. During Bilge’s reign, the Second Turkic Khaganate enjoyed a renaissance of steppe culture. This is when the Orkhon Inscriptions mentioned earlier were erected (c. 732 CE) – a proud summation of the trials and triumphs of the Ashina-led nation. In an interesting twist, these inscriptions were written in the Turkic runic script, the first known writing system of the nomadic Turks, likely inspired by interactions with literate cultures. They stand as the “epitaph” of the Göktürk Empire, composed by those who brought it back to life. We hear Bilge Qaghan’s voice through them: dignified, somewhat mournful of past mistakes, and admonishing future generations to remain true to their heritage.

Yet even Bilge Qaghan could not halt the changes that churned across Central Asia. After his death, the Second Khaganate began to weaken. The unity he and Kul Tegin forged started to crack as subsequent khagans were less competent. Vassal tribes sensed the faltering and became restive. In the southwest, powerful new players – the Tibetan Empire and the Tang – pressed against Turkic territories. Meanwhile, within the empire, ambitious subject tribes like the Basmil, Karluk, and a rising star known as the Uyghurs were waiting in the wings. In the year 744 CE, these three tribes formed a coalition, rebelled, and overthrew the Ashina regime. The last Göktürk khagan (an Ashina descendant) was killed – legend says his head was sent to the Tang emperor as a trophy, a gruesome bookend to the Ashina’s century-long imperial saga. The Wolf Banner of Ashina was lowered at last.

However, Central Asia abhors a power vacuum. The victorious Uyghurs quickly established their own Uyghur Khaganate (744–840) over much of the former Göktürk realm. Interestingly, the new Uyghur ruling elite did not belong to the Ashina bloodline – they were a different clan (the Yaghlakar), breaking a long tradition of Ashina leadership among steppe empires. This was a significant changing of the guard. Yet, the Uyghurs inherited many aspects of Göktürk governance and culture, and they saw themselves as rightful successors. In this next chapter of steppe history, some surprising developments were afoot: the nomadic empire was about to get a taste of city life.

Before we move on, let’s pause and reflect on the arc so far. The Ashina had risen like a meteor, blazed brilliantly, fragmented, then risen again like a phoenix, only to fall in the end. Their journey from wolf-mother myth to empire left deep imprints. The Turkic peoples had spread far and wide, and the concept of a Khaganate – a great steppe empire – had become established. The cycle of rise, fall, and revival feels almost like the cycle of seasons on the steppe: spring growth, summer glory, autumn fragmentation, winter dormancy, and then a new spring under a different tribe. Indeed, this cyclical pattern would repeat with others, but each iteration brought something new to the tapestry of history.

Now, the mantle of steppe hegemony passed to the Uyghurs, and it is through the eyes of an outsider during the Uyghur era that we gain an extraordinary window into nomadic life in the 9th century.

Tamim Ibn Bhar's Journey

In the year 821 CE, a curious visitor arrived at the court of the Uyghur Khagan. He was not Chinese or Persian, but Tamim ibn Baḥr, an Arab traveler and envoy of the Abbasid Caliphate. Tamim’s journey from the Abbasid realms (possibly Samarkand or Baghdad) to the remote steppes of Mongolia was an epic in itself – taking him across desert, mountain, and grassland. When Tamim returned home, he recorded a remarkable account of what he had witnessed in the land of the Uyghurs. His report provides a rare firsthand look at a nomadic empire in its prime, and it both confirms and contrasts what other sources tell us about steppe life. By comparing Tamim’s observations with Chinese chronicles and earlier legends, we can paint a vivid picture of how nomads lived, governed, fought, and dealt with outsiders.

Tamim ibn Bahr’s travel narrative begins with the sheer breadth of the journey. He notes that the Uyghur country was so cold that travel was only feasible in the warmer half of the year. He rode on relay horses provided by the Uyghur Khagan – a kind of express messenger system where fresh horses and guides awaited at intervals. Even with this support, he spent twenty days crossing uninhabited steppes. Imagine the scene: Tamim and his small retinue galloping across an ocean of grass, day and night, with nothing but endless plains and sky in sight. For twenty days they saw no towns, perhaps not even a single house – only the occasional nomad encampment of felt tents belonging to the relay staff. Each evening, they likely pitched camp under the brilliant canopy of stars, and each morning they broke the thin ice on waterholes to drink, enduring the biting wind. Tamim carried provisions for those long weeks, knowing there would be no markets until they passed this wilderness.

After this vast emptiness, Tamim’s surprise is pretty palpable when he describes what came next. Suddenly, he entered a region of closely clustered villages and cultivated fields. For another twenty days he traveled through farmland – yes, farmland in the land of nomads! These were areas where people grew crops and lived in houses. He remarked that most inhabitants were Turks, but among them were "fire-worshippers" (likely the Zoroastrians mentioned ealier or Sogdian Iranian settlers) and “Zindiqs” (a term Muslims used for Manichaeans or heretics – and indeed the Uyghur elite had adopted Manichaeism, a religion from Persia). This shows that the Uyghur Khaganate, unlike the purely pastoral Göktürks, had diverse religions and populations. They presided over an integrated society of both herders and farmers, natives and foreigners. The old stereotype of nomads as purely wandering tent-dwellers was no longer entirely true here – a “far cry from the traditional picture of pastoral nomad existence,” as one historian notes. Tamim’s astonishment at finding thriving agriculture and permanent villages under the rule of a steppe khan really underscores how much the nomadic empire had evolved.

Finally, after forty days, Tamim reached the king’s town – the capital of the Uyghur Khagan. This was likely Ordu-Baliq (also called Karabalghasun), the Uyghur imperial city in the Orkhon Valley. Tamim describes it as a great town, rich in agriculture, surrounded by districts full of cultivation and closely-settled villages. The city boasted "massive walls with twelve iron gates", bustling markets, and workshops of various trades.

This depiction aligns with archaeology, which shows that Ordu-Baliq had palace complexes, monasteries, and streets – a true city built by nomads. One cannot overstate how extraordinary this was: a nomadic royal clan that only a few generations before roamed in felt tents had now constructed a permanent, fortified capital with all the trappings of urban life. It’s as if the steppe itself had sprouted a stone citadel, illustrating the adaptability of nomadic governance.

Yet, even in this urbane setting, the Uyghur rulers kept ties to their roots. Tamim notes that from several miles away he could see a "resplendent tent made of gold" perched atop the Khagan’s palace or fortress. This gilded tent, large enough to hold a hundred men, symbolized the Uyghur monarch’s authority. It was a portable throne room, a bit of the nomadic spirit gleaming over a sedentary city. We can imagine another scene through thee eyes of the traveler: as Tamim approached, perhaps at dawn, the sunlight struck this Golden Tent, making it shine like a lantern above the city walls, reminding all that the Khagan was the master of both steppe and town. (This golden tent motif would show up in later times – the Mongols and even Turkic rulers in the west were said to use golden tents as mobile palaces, such as the famed “Golden Horde” deriving its name from the golden tent of Batu Khan.)

Tamim On Outsiders

Tamim’s account also highlights how the Uyghur Khagan related to outsiders: notably, he records that the Uyghur king was married to a Chinese princess, and that the Emperor of China (the Tang) sent him 500,000 rolls of silk every year as part of their alliance. This information is corroborated by Chinese sources, which describe the Tang-Uyghur diplomatic marriages and hefty silk tributes given to the Uyghurs, essentially to keep them friendly and to enlist their military aid (the Uyghurs had helped the Tang suppress a major rebellion decades earlier). It reveals a great deal about nomadic governance and foreign policy: the Uyghur Khagans skillfully played the role of power-brokers, extracting wealth (like silk) from China and possibly selling some of it west via the Silk Road, and in return providing military support or at least peace on the border. The marriage alliance also implies a degree of mutual respect – the “barbarian” steppe king was now a royal son-in-law of the Chinese emperor, a dramatic reversal from the days when Ashina princes had to ask (and fight) for brides.

This diplomatic clout went hand in hand with military might. While Tamim does not detail battles, the Uyghur army was reputedly formidable, mixing traditional mounted archers with some heavy cavalry. Chinese and Arab sources mention Uyghur cavalry covered in armor (for both rider and horse) in cataphract style, as well as swift mounted archers. The nomads remained masters of mobile warfare; even as they built cities, they did not forget how to fight as steppe warriors. The Uyghur Khaganate’s fall would eventually come not from China or Arabia, but from another nomadic people – the Kyrgyz, who toppled the Uyghurs in 840, in part due to internal weaknesses and perhaps climate shifts. But during Tamim’s visit in 821, the Uyghur realm was at its zenith, showcasing a fusion of steppe and sedentary life.

Comparing Tamim ibn Bahr’s report to earlier accounts of nomads, we see both continuity and change. Chinese chroniclers in Han times (2nd century BCE) described the Xiongnu (an earlier steppe empire) as having “no cities, no agriculture, living in felt tents and moving with the seasons.” That was largely accurate for the Xiongnu and even for the Göktürks early on. A Chinese poet once lamented that nomads “have pasture for walls and yurts for houses.” Yet here was Tamim, centuries later, marveling at walls of brick and iron gates built by their descendants. The nomadic mode of life was flexible – given the right circumstances, nomads could settle and urbanize to an extent, all while retaining their core military advantages.

Other travelers after Tamim also left colorful observations. For instance, when the Mongols rose (much later, in the 13th century), European envoys like William of Rubruck would similarly describe the Mongol khans living in lavish tents but establishing administrative cities like Karakorum. There’s a fascinating thread from Tamim’s Uyghur Khagan to Genghis Khan’s court: both highlight how steppe governance could oscillate between mobility and stability. A khan might sit on a throne one month and on a saddle the next, ruling over farmers in one region and herders in another.

Tamim ibn Bahr’s journey, placed in context, illustrates nomadic life in full spectrum: the hardships of travel across inhospitable steppes, the hospitality of yurts in lonely places, the flourishing farms under nomad protection, the cosmopolitan capital with traders and priests from many lands, and the awe-inspiring figure of the Khagan himself, part warrior-part king. It’s a humanizing and insightful counterpoint to purely sedentary perspectives. We learn that these “steppe barbarians,” as some might label them, were capable of statecraft, commerce, and cultural tolerance rivaling their settled neighbors. They governed by charisma and kinship, fought with both courage and cunning, and engaged with outsiders through war when confident and through alliance when prudent.

Turks Embrace New Faiths and New Lands: Rise of the Islamic Turkic Powers

Even as the Uyghur Khaganate was flourishing in the northeast of Central Asia, profound transformations were underway to the west and south. The 8th to 10th centuries saw many Turkic peoples gradually convert to Islam and establish their own states in former Persian and Central Asian territories. In a sense, the energy of Turkic expansion flowed out of the steppe and into the surrounding civilizations, like a great river branching into new channels.

One major turning point was the Battle of Talas in 751 CE, where a Chinese Tang army was defeated by the Arab Abbasid forces near the Talas River (in present-day Kazakhstan). This clash halted Chinese expansion into Central Asia and ensured that the region’s future would tilt toward Islamic influence rather than Chinese. In the aftermath, Turkic tribes in the western parts of the steppe and Transoxiana (the lands beyond the Oxus River) increasingly interacted with the Muslim world. Many served as mercenaries or elite guards for Islamic rulers, learning about Islam along the way. Over generations, whole tribes began adopting the new faith, often as a way to integrate with the wealthy Muslim cities and trade networks.

By the 10th century, the first Islamic Turkic state emerged: the Karakhanid Khanate. Founded by the Karluk Turks and their allies, the Karakhanids converted to Islam (the khan Sultan Satuq Bughra Khan’s conversion is legendary) and took control of cities like Kashgar and Balasagun. They became patrons of mosques and madrasas, marrying the steppe nomad warrior ethos with the administration of a Persianate-Islamic state. It was a dramatic cultural shift – akin to the likes of a wild steppe horse accepting a new rider, the Turkic nobility began to carry the mantle of Islamic kingship. They still loved hunting with hawks and riding out with their retinues, but they also built irrigated gardens in their capitals and sponsored the writing of literature in Turkic using the Arabic script.

Further west, another Turkic group of the Oghuz federation, led by the family of Seljuk, also embraced Islam and ventured into Iran and beyond. In the 11th century, these Seljuk Turks exploded onto the scene, conquering Khurasan and Persia, then Iraq and Syria, even Anatolia after the famous Battle of Manzikert in 1071. The Great Seljuk Empire, at its height, stretched from the Hindu Kush to the Mediterranean. Here were the descendants of steppe nomads sitting on the thrones of ancient civilized regions, ruling over farmers and city-dwellers. They took Persian viziers and adopted many local customs, yet the military core remained Turkic cavalry. One Seljuk Sultan, Alp Arslan, had an army that still relied on the classic horse-archer tactics of the steppe to crush a Byzantine force, capturing the Roman emperor – a scenario not unlike an earlier Turkic khan humbling a Chinese emperor’s armies on the steppe. History, it seemed, was playing a rhyming verse, with Turkic horsemen now fighting under the banner of Islam rather than the wolf banners of Tengri, but still very much employing the strategies of their ancestors.

This era also saw Turkic soldiers becoming kingmakers and rulers in other places. The Ghaznavid Empire in Afghanistan and India was founded by a Turkic slave-soldier turned sultan (Mahmud of Ghazni’s father was a former slave guard of the Samanids). The Khwarazmian Empire in Persia (12th century) likewise emerged from a line of Turkic mamluk governors. In the Middle East, the Abbasid Caliphs themselves increasingly relied on ghilman – slave warriors of Turkic origin – to fill their armies and palace guard. These ghilman, essentially early Mamluks, grew in influence and often power behind the throne.

This process was not overnight or uniform – it was a complex blending. But by the 11th–12th centuries, one could see a mosaic of Islamic Turkic powers dominating West and Central Asia. Culturally, this was a metamorphosis: the Turkic nomads absorbed the religion and much of the high culture (art, architecture, language) of the lands they conquered. One could say they forged a new identity, much as raw iron is forged into steel – the hardness of their steppe heritage combined with the refined carbon of Islamic civilization. The result was something stronger and enduring. For example, the Seljuks patronized great works of art and learning, blending Turkic, Persian, and Islamic elements to create a rich new tradition. They commissioned mosques but decorated them with patterns reminiscent of weaving and knots from their nomadic art. Poetry in Persian praised the Sultan’s battles as "a hunter’s chase", imagery a nomad would love. We see here a powerful analogy of cultural transformation. Just as a nomadic warrior might swap his felt cloak for a silk robe without forgetting how to shoot a bow, the Turkic societies adopted Islam and urbane customs yet retained a certain steppe vigor in their politics and warfare.

Throughout these centuries, the memory of the Ashina and the steppe empires was not lost. For example, the Seljuks and other Turkic dynasties often invoked “Turkic” heritage with pride. They knew that their forefathers roamed free in the steppe, and this gave them a sense of military superiority. The concept of Tengri’s favor morphed into the Islamic concept of Allah’s will, but leaders still liked to think that the sky (or heaven’s) mandate favored the bold horseman.

It’s also worth noting a key continuity: political fragmentation remained common. Just as the Göktürk Empire split among rival clans, the Seljuk Empire too eventually fragmented among various sultans and atabegs. The Turkic world, whether steppe pagan or Islamic sultanate, valued kinship ties and personal loyalty which could both build and break realms in the absence of strong succession systems. This set the stage for perhaps the most dramatic nomadic eruption the world would see – one that would briefly unify the fractious tribes once more in a common cause of conquest.

The Mongol Shockwave Of A New Steppe Empire and Its Impact

By the early 13th century, the Turkic powers had dominated Central and Western Asia for generations. But in the far eastern steppe, in Mongolia – the ancestral homeland of the earlier Xiongnu and Göktürks – a new power was rising. This time, it was not a Turkic clan but a Mongol tribe that would unite the nomads. Interestingly, during the era of the Göktürks and Uyghurs, the Mongolic-speaking tribes (like the Shiwei or forebears of the Mongols) were relatively obscure, dwelling in the forest-steppe north of Mongolia. Chinese records from Tang times mention a tribe called Mengwu (Menggu) among those fringe peoples – an early reference to the word "Mongol." They had little influence then, overshadowed by the great Turkic empires. We could liken them to embers glowing quietly while brighter flames shined elsewhere. But those embers never died..

Fast forward to 1206 CE, a charismatic warlord named Temujin from the Mongol tribe succeeded in doing what many thought impossible – he united the region's feuding Mongol and Turkic clans under his leadership. He took the title Genghis Khan, meaning "Universal Ruler," and unleashed the Mongol conquests that would forever change the course of history. The Mongols swiftly conquered the Tangut kingdom of the Jin dynasty of northern China, then swept westward through Central Asia, annihilating the Khwarezmian Empire by the 1220s. In doing so, they effectively ended the line of Central Asian Turkic empires (at least for a time), replacing them with a Mongol empire that stretched across Eurasia. The steppe was now under new management.

The Mongol Empire at its height, was the largest contiguous empire ever known, and it was built on the same fundamentals of steppe warfare and organization that the Ashina and others had used – only honed to a razor's edge. Mongol armies were essentially all cavalry highly disciplined. They used intelligence networks, signal communication (via beacon fires and flags), and psychological tactics (like terrifying repute) to complement their horse archery and mobility. They could cover astonishing distances. an analogy often used is that "the Mongols moved like a sandstorm across continents." Like earlier nomads, they primarily lived off the land (or their herds) and could appear where least expected. But unlike any before, they showed relentless, calculated brutality in subjugation, which struck terror from Hungary to Korea.

Notably, the Mongols did not discriminate by culture or religion regarding conquest – they toppled Islamic, Christian, Buddhist, and Confucian states alike. Central Asia and Iran ended several Islamic Turkic dynasties, ushering in a period of Mongol khanates (the Ilkhanate in Persia, the Chagatai Khanate in Central Asia, etc.). Ironically, these Mongol khans assimilated into the local cultures within a few generations, many adopting Islam and Turkic or Persian languages. For example, in the western part of the Mongol Empire, the Golden Horde khans (descendants of Genghis's son Jochi) settled by the Volga River and eventually became Turkicized and Muslim, blending with their Kipchak Turkic subjects. Thus, in a twist of fate, the conquests of the Mongols ended up reinvigorating Turkic influence in some regions – the Chagatai Khanate in Mawarannahr became a Turkic-speaking state after the Mongol elite adopted the local tongue. In Anatolia, the chaos after the Mongol invasions gave breathing room for a small Turkic beylik under Osman to grow, eventually into the Ottoman Empire. So even though the Mongols conquered the Turkic world, they also catalyzed new Turkic-led polities in the aftermath, a kind of renewal in altered form.

One dramatic chapter of the Mongol era brings us full circle to the theme of nomads interacting with "outsiders": in this case, the Mamluks of Egypt, who famously halted the Mongol advance in the Middle East. The Mongols had sacked Baghdad in 1258, ending the Abbasid Caliphate, and seemed poised to push into Egypt. But at the Battle of Ayn Jalut in 1260, a Mongol army was defeated for the first time in open battle by a force of Mamluks – who were themselves largely Turkic steppe warriors! This brings us to the final piece of our puzzle: who were the Mamluks, and how did steppe warfare save a civilization instead of destroying it?

Mamluk Warriors, Steppe Knights Defending a Foreign Land

The Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt and Syria (1250–1517) was, in essence, the last flourish of the medieval steppe military tradition, but transplanted onto the soil of the Nile Valley. The very word Mamluk in Arabic means “owned, or bought man,” reflecting their origin as slaves. These were no ordinary slaves, however; they were usually boys of Turkic (and later Circassian) origin, purchased from the slave markets of the Black Sea steppe. Many of them were Kipchak Turks – in other words, born on the steppes north of the Caspian and Black Seas, speaking a Turkic tongue and raised in the saddle. Sold usually around adolescence, they were brought to Cairo or Damascus, converted to Islam if not already Muslim, and trained intensively as elite cavalry soldiers. It was a hard but opportunistic life: cut off from their birth families, they bonded with their comrades-in-arms and with their patrons. Over time, these slave-warriors became the real power behind the throne of the Ayyubid dynasty (descendants of the Sultan Saladin) and eventually took direct control, establishing their own sultanate.

Despite now serving as the protectors of a settled, rich country with ancient cities and monuments, the Mamluks remained culturally attached to the steppe martial ethos. They trained relentlessly in archery and horsemanship, staging elaborate war-games and tournaments (the furusiyya* exercises) to keep their skills razor sharp. Contemporary chroniclers wrote of Mamluk youths spending hours on end practicing shooting targets while at full gallop and performing complex maneuvers in formation. They were required to master the famed composite bow – a weapon of wood, horn, and sinew that could outrange the crossbows of European crusaders. A Mamluk cavalryman could nock, draw, and loose arrows in rapid succession while his horse thundered across the field. It was said that a good Mamluk archer could hit a small target at 70-80 meters with consistency – an incredible feat of accuracy and control.

In battle, the Mamluks employed all the classic tactics of their steppe heritage. They would harass the enemy with swift horse archers, using hit-and-run attacks that peppered foes with arrows but kept their distance from any solid infantry line. Feigned retreats were a favorite ploy. a Mamluk vanguard might charge and then suddenly wheel around as if in panic, luring pursuing enemies out of their cohesive ranks, only to have the Mamluk main force envelop and counterattack at the right moment. They used encirclement and ambush brilliantly, often hiding reserves in nearby wadis or behind hills – akin to the way Huns or Göktürks vanished behind terrain only to reappear unexpectedly. Heavy cavalry with lances and swords would then crash in to finish a disordered enemy. Many Mamluks wore mail or lamellar armor and carried a curved saber perfect for slashing from horseback. Their horses, often of Arabian and steppe mixed stock, were swift and hardy, sometimes armored with chamfrons and chest pieces for protection in close combat.

At Ayn Jalut, this expertise met the Mongols head-on. The Mamluk general (and future Sultan) Baybars orchestrated the battle by first using a feigned retreat to draw the Mongols into a chase. The Mongols, confident from prior victories, took the bait. Once the Mongol riders were stretched out and less organized, the Mamluks sprung their trap: hidden bands of Mamluk cavalry swooped in from the flanks, while the retreating force turned to press the attack. The Mongols found themselves encircled and bombarded by arrows from all sides. According to accounts, the sky was darkened by arrows – a tactic both Mongols and Mamluks excelled in, but now the Mamluks had the upper hand of preparation and positioning. The result was a decisive victory that halted the Mongol march west. For the first time, a Mongol army had been beaten in a direct confrontation, and it was done by fellow steppe warriors, though fighting under a different banner. One could say that the only force capable of definitively stopping the onslaught of nomadic conquest was another group of nomadic warriors, transplanted and transformed. The Mamluks protecting Cairo were essentially distant spiritual cousins of the Ashina horsemen who once guarded Ötüken.

In the Mamluk Sultanate, the steppe traditions fused with the context of a Middle Eastern kingdom. Mamluk sultans took on grand Islamic titles and built beautiful mosques and schools in Cairo, yet they also maintained the Steppe custom of succession by merit (or force) rather than hereditary rule. Each new sultan often had to seize power through a palace coup or be elected in a council of senior emirs, much like a Kurultai (tribal council) choosing a khan. The Mamluk elite continued to replenish their ranks with fresh recruits from the steppe, ensuring that the culture of horseback archery was continually renewed with hardy youth who had spent their childhoods in yurts and open pastures. In a way, one can visualize the Mamluk state as a tree with roots in the Nile soil but seeds from the Eurasian plains. It bore fruits of high civilization, yet was fertilized by a constant influx of steppe vitality.

Their military success was not limited to fighting Mongols. The Mamluks also definitively ended the era of the Crusades by expelling the last Crusader strongholds by 1291. In those wars, too, their combination of tactics – from disciplined archery volleys to fearless cavalry charges – proved superior. Chroniclers from Europe were stunned by the mobility and coordination of the Mamluk cavalry, noting how they would “dance” around the Frankish armies, who were far slower and less flexible.

By the 14th century, the Mamluk Sultanate had become a major center of the Islamic world, economically and culturally, partly thanks to the stability provided by their military prowess. But like the empires before, eventually their vigor waned, especially as gunpowder weaponry began to eclipse the horse-bow combo. In 1517, the Ottoman Turks (another branch of the great Turkic family, ironically) conquered Egypt, ending the Mamluk era. Yet, the romance of the Mamluk knights – former slave boys turned kings, steppe warriors defending the realms of ancient pharaohs – remains one of history’s fascinating stories.

From the Steppe to the World

The chronicle of the Ashina tribe and the nomadic steppe empires is a sweeping epic of adaptation and transformation. It begins with a persecuted clan in the wilderness, forged in the crucible of hardship and symbolized by a wolf and a piece of iron. It ascends to dazzling heights as the Ashina and their fellow Turkic nomads establish one of the most formidable empires of late antiquity – a polity built on horseback and courage, governed by tribal codes and personal loyalties, yet far-reaching in its diplomacy and trade. It then fragments and reshapes, like a kaleidoscope turning: the same pieces forming new patterns with each twist. The Uyghurs emerge, adopting agriculture and building cities while embracing their forebears' mobility. The Turks move outward, converting to a new faith and, in doing so, carrying their traditions into new lands, as seen in the courts of Bukhara, Isfahan, and Delhi. The Mongols burst forth, temporarily uniting the steppe in an unprecedented explosion – but even that explosion scatters seeds that take root as new powers (Timur's empire, the Ottomans, etc.). Finally, the Mamluks are a poignant example of how the steppe ethos could be harnessed to defend a settled civilization, not just to conquer it.

Across these centuries, a few threads bind the story. The first is the centrality of the horse and the bow, the tools that made nomads masters of vast distances. A Mongol archer, a Göktürk cavalryman, and a Mamluk lancer shared a common skillset that allowed them to dictate the terms of war to slower, footbound foes. The second is the fluidity of nomadic society – its ability to transform almost chameleon-like when necessary. One century, the Turkic Khans are shamanic and illiterate; a few generations later, their grandsons are Muslim sultans patronizing algebra and astronomy without entirely losing that primal toughness. One moment a nomad clan serves as humble blacksmiths; the next, they are kings who make emperors kneel. And the third is the cycle of rise and fall that seems inherent to steppe politics. Without a capital city's stone foundations or a bureaucracy's paperwork, these empires relied on personal strength and unity. When those faltered, the empire could dissipate as quickly as a desert mirage under the noon sun. But a new power would often rise from the old, like grass after rain.

Culturally and politically, the transformations were profound. We can use an analogy of metallurgy to sum it up: the nomads took the raw iron of their ancient traditions. They tempered it in the fires of contact with great civilizations – whether through trade, war, or faith – and forged new blades that would order history in unexpected ways. The sword of Tengri became the sword of Islam in many cases, yet it was wielded with the same calloused, skillful hands.

By around 1400 CE, the age of steppe empires begun by the Ashina had largely run its course. Timur (Tamerlane), a Turkic-Mongol conqueror, was perhaps the last to reunite a large swath of the steppe and sedentary world by force of arms, and even he built on the legacy of Genghis Khan. Gunpowder and new political formations started tying the balance in favor of settled states for good. But the legacy of those nomadic empires is still felt. The Turkic migrations permanently changed the demography of Central and West Asia – giving us the Turkic nations from Turkey to Kazakhstan today. The Mongol unification of Eurasia facilitated exchanges of technology, ideas, and even disease (the Black Death traveled along Mongol routes) that profoundly affected world history. The concept of mobile, meritocratic elite warriors persisted – it can be seen in later cavalry traditions and even modern notions of mobile warfare.

The story of the Ashina and their steppe compatriots adds a vivid swath of color, the color of the open sky and golden grass, blood on steel, campfires glowing under tent canopies, and silk banners flying in fierce winds. It's a story that reminds us that civilization doesn't only spring from fertile river valleys and city walls; it can gallop out of the wild plains, born on the backs of nomads who dream as big as any emperor. The Eurasian Steppe was not an empty void between China and Europe – it was its own world, pulsing with life and ambition, producing leaders who would shock continents. From the wolf-child of Ashina to the Mamluk knight, the nomad's journey remains one of the most enthralling narratives, showing how human societies can transform across centuries – adapting like water taking the shape of whatever vessel it finds, yet always retaining its essence. The next time one gazes at the steppe's endless horizon, remember that it was once the cradle of empire, and its children rode out to make the world their own.