They Carry the Oldest DNA. Now They’re Fighting to Protect it.

Are humans animals? It’s a question that might make you pause. Biologically, Homo sapiens is indeed an animal. Yet in our quest to feel special, we often forget our wild origins. One best-selling book, Yuval Noah Harari’s Sapiens, paints a sweeping picture of our species’ journey from humble foragers to world rulers. But long before modern civilization — before the Southern African Customs Union or any nation’s borders — small bands of humans roamed Southern Africa living in tune with nature. Among them were the San people of Africa, perhaps the closest living link to our most ancient ancestors.

Their story is one of contagious curiosity and vivid storytelling, bridging science and ethics with wonder and humor. It’s a tale of the “bushmen” San people (as outsiders once called them) carrying the oldest DNA in the world, and fighting the newest battle for dignity and data sovereignty.

Footprints of the First Humans in the Kalahari

Let’s magine an early morning in the Kalahari Desert thousands of years ago. A small family clan of San people wake under acacia trees. They speak in gentle click consonants unique to their language, voices blending with birdsong. They are hunter-gatherers, living much as their ancestors did for untold generations. In a way, this could be a scene from the very ‘morning’ of humanity.

The San people of Africa, often referred to historically as “Bushmen,” are likely the oldest population of humans on Earth. Genetic studies – think of them as high-tech ancestral family trees – suggest the San are directly descended from the original population of early human ancestors who gave rise to all other groups. In other words, if you trace the human family tree all the way back, you’d find the San at a trunk from which all other branches grew.

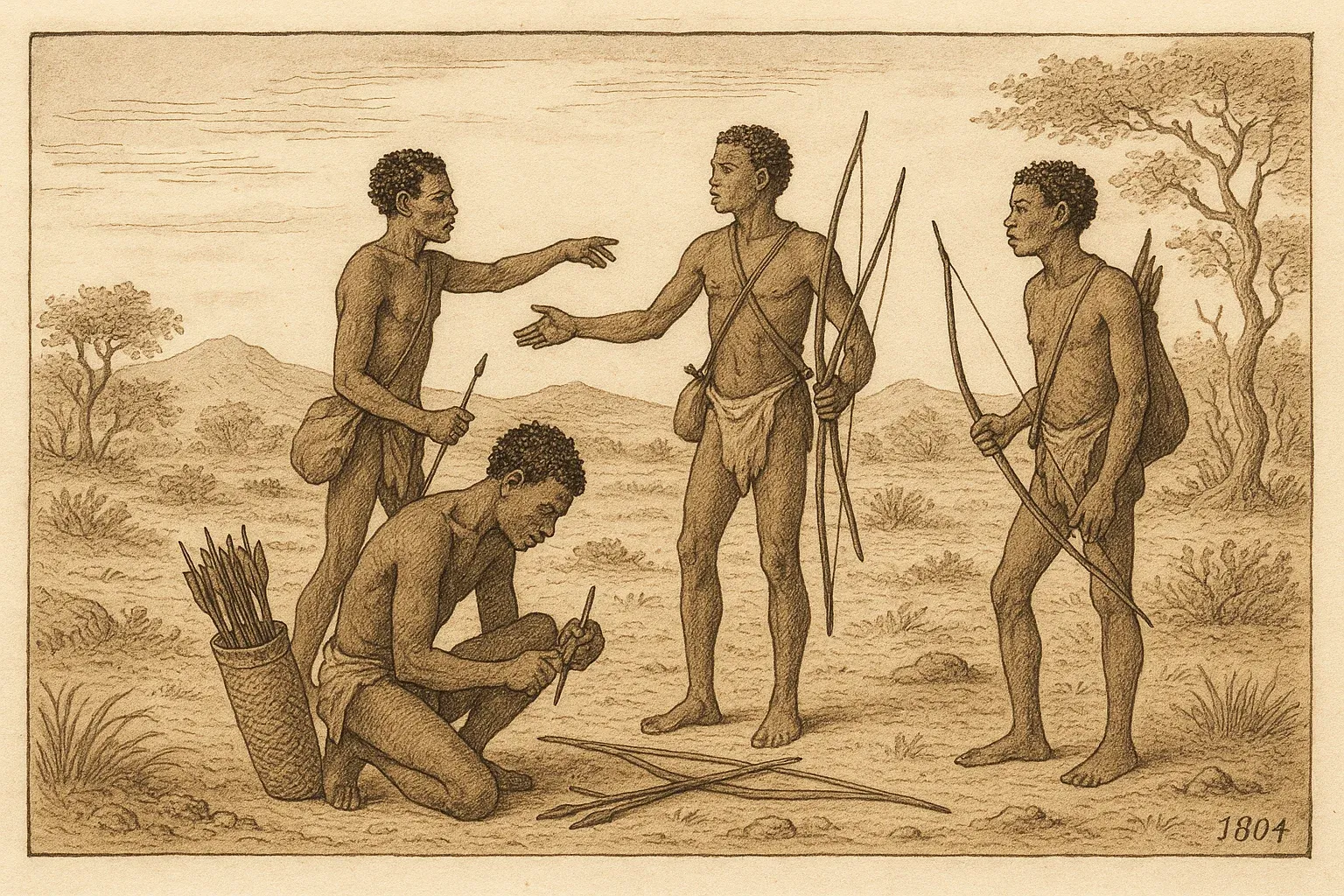

The San (who prefer their own group names like Juǀʼhoansi or ǃXuun, rather than the colonial label “Bushmen”) have lived as nomadic foragers for thousands of years. They traversed what is now Botswana, Namibia, South Africa and beyond – long before lines on a map or trade treaties like the S.A.C.U existed. They left traces of their lives in ancient rock art on cave walls. Even today, you can find vivid red ochre paintings of springbok antelopes and hunters on rocky outcrops, a San artist’s message across millennia. Beauty is in the eye of the beholder, and to those who understand these paintings, they are breathtaking. (Ironically, some colonial observers saw the San’s simple lifestyle and appearance and ignorantly dismissed them as “ugly people” – a cruel misjudgment that says more about the observers’ prejudice than about the San. The San’s culture and knowledge of the land had and has its own profound beauty.)

By all accounts, the San are among the most storied African tribes, with traditions stretching back to the Stone Age. Anthropologists often describe them as “living fossils” – not because they are old (many San are lively and modern in their own ways!), but because their way of life and DNA preserve a snapshot of what early humans might have been like. They practiced a semi-nomadic life, tracking game with bow and arrow and gathering wild tubers and berries. They mastered survival in harsh desert where others would perish, reading the landscape like a library of wisdom. Every rock, every plant had a use or a story. They also have a rich oral tradition of myths about the stars and moral lessons, shared around campfires under the African night sky.

The DNA Discovery and Hunting for Our Origins

For scientists curious about human origins, the San people’s blood holds the irresistible treasure of ancient DNA. DNA is the genetic code that links all life, and it carries the history of our species. But what is DNA exactly? DNA is made of repeating units called nucleotides – think of them as four chemical “letters” (A, T, C, G) that form sequences spelling out instructions to build a human. This code is 99.9% identical in all people, yet the tiny differences hold clues to where our ancestors lived and migrated. Essentially, your DNA is a biological diary written by your ancestors, with each generation adding a few new notes. The San’s diary, it turns out, is exceptionally long and detailed.

In 2010, a team of geneticists set out to read that diary. They collected DNA from a few elderly San individuals in Namibia (along with South African Archbishop Desmond Tutu’s DNA as a reference). They sequenced their genomes – meaning they decoded all the DNA letters in their cells. The results sent shockwaves through the scientific world. The San genomes were full of rare genetic patterns not seen in other populations, indicating a deep, ancient lineage. One headline shouted that the San were “the world’s most ancient race.” Indeed, a major study analyzing genetic diversity across Africa found the San to be among the most genetically diverse groups on the continent. High genetic diversity is a clue: it often implies a population has been around a very long time (accumulating many DNA variations) – in this case, possibly the oldest continuous population of humans on Earth.

The San’s DNA held pages of human history that scientists thought were long lost. In our global family, all humans are closely related – for context, how much DNA do siblings share? On average about 50% (since each sibling gets roughly half their DNA from each parent). Yet the San carry unique gene variants suggesting that their ancestors diverged from all other humans very early.

One genetic marker in particular stood out: haplogroup L0d (and a related one, L0k). This haplogroup is part of our mitochondrial DNA – a tiny bundle of genes we inherit exclusively from our mothers, passed down through maternal lines like a genetic surname. Haplogroup L0d is the most divergent (earliest-branching) mitochondrial lineage ever identified in living people, and it’s found at its highest frequency in southern African San groups.

In plain language, L0d is like an ancient matriarch’s signature, and it suggests the San’s maternal ancestors have been in south Africa for well over 100,000 years, tracing back to near the birth of Homo sapiens.

To put that in perspective, let’s consider time: If you have a time machine and go back 100,000 or 200,000 years, you might meet the great-great-(...)-great-great-grandmothers of today’s San, wandering those same lands. They might not recognize the clothing or gadgets we have now, but genetically and anatomically, they would be humans like us, Homo sapiens. That was around the time our species was young and finding its way. The Sapiens book you might have read – with its talk of a “Cognitive Revolution” and early human societies – describes exactly the kind of world in which the San’s ancestors thrived. The San’s DNA connects directly to those chapters of the human story.

Now, how did scientists actually decode the San genome? Here’s where modern science enters with its high-tech wizardry. Decoding DNA used to be arduously slow – the first human genome sequencing project in the 1990s took 13 years to complete. But gene-sequencing technology has advanced at an awe-inspiring pace. When did DNA testing start?

As a tool for identification, DNA testing really began in the mid-1980s. In 1984, British geneticist Alec Jeffreys developed DNA fingerprinting, a technique that first allowed individuals to be compared based on their DNA. (Fun fact: Jeffreys’ “eureka moment” came when he realized that specific patterns in DNA, called minisatellites, differed between people – except for identical twins – enabling unique IDs. The first criminal was caught using DNA evidence by 1987, and suddenly, crime dramas were never the same).

From that breakthrough, we leaped to sequencing whole genomes. The process that once took years can now be done in days or even hours. Today, a lab can sequence a person’s entire genome in a day or two – an astonishing feat when you consider it’s composed of 3 billion DNA letters. (For context, a simple paternity DNA test result can be ready in 2-5 days in a lab, and a consumer ancestry test usually takes a few weeks to process. The waiting is often just shipping and queue time, the actual machine sequencing might only take a day.)

So the team sequencing the San men’s DNA in 2010 had powerful tools at their disposal. They read each man’s 6 billion DNA letters (we get ~3 billion from mom + 3 billion from dad) and compared them to known genomes. The data confirmed that the San carried many unique genetic variants and belonged to some of the earliest-known human haplogroups both in mitochondria (L0d/L0k) and Y-chromosome lineages (the San also have some of the oldest Y-chromosome branches, dubbed haplogroups A and B, going back to an Adam of sorts).

Essentially, researchers had found a long-lost epilogue of a book – the human story – and that chapter was set in the Kalahari, written in the blood of the San people.

The findings were celebrated in scientific circles. They helped pinpoint Africa (particularly southern Africa) as the cradle of all modern humans. One research team even proposed that a specific region in Botswana might have been an early homeland where our species first flourished before spreading out. Not everyone agrees on the precise location (science is, after all, an ongoing debate), but the consensus is clear: all humans ultimately descend from African ancestors, and the San are a window into that primordial past.

It’s humbling and a little mind-bending – like realizing that all the billions of humans alive today are really just a big extended family, and one of our oldest branches still lives quietly in the desert, telling stories by the fire.

In the Genes: Clear Science with a Sense of Wonder

Let’s take a breather before we continue, and break down some clear science behind all this, delivered with a dose of wonder (and maybe a pinch of humor). We’ve talked about DNA as a “code” or “diary,” but how does it really work? Here’s a quick crash course in genetics, San-story style:

- DNA Basics: As mentioned, DNA is made of repeating units called nucleotides. Each nucleotide consists of a sugar, a phosphate, and one of four nitrogenous bases (A, T, C, or G – the famous letters). Picture a very long ladder twisted into a double spiral, each rung of the ladder is a pair of these bases (A pairs with T, C pairs with G). This sequence of letters is the code that builds every part of you. The San’s DNA has a few unique “spelling differences” in that code compared to, say, a European or Asian person’s DNA, but crucially, we’re all 99.9% the same at the genetic level. The differences are the fun part though – they’re what geneticists study to trace ancestry or find disease genes.

- Ancestry and Haplogroups: Some parts of our DNA are very special for ancestry tracking. Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) is passed down from mother to child, unchanged except for occasional mutations. It’s like a single, long line of maternal descent. Scientists have catalogued major mtDNA lineages called haplogroups that branch off as mutations accumulate over tens of thousands of years. Think of haplogroups as big family clans in the genetic sense. The one called L0d (and its sibling L0k) found in the San is like the grandmother of all haplogroups. It’s the oldest branch on the human family tree we’ve identified. In fact, all non-African people in the world carry mtDNA haplogroups that descend from a later branch called L3 (which gave rise to M, N, etc., after a group of humans migrated out of Africa). But the San and some other African groups still carry L0 variants, the OG lineages that never left home. This doesn’t mean the San stopped evolving – not at all. It just means their maternal lines today trace back to very ancient roots that predate those migrations. It’s akin to finding a living city where people still speak a language closely related to Latin, while elsewhere, folks have moved on to Spanish, French, Italian, and so on. The San’s genetic language is archaic but still spoken, giving scientists a chance to learn how the original “Latin” of our DNA might have looked.

- Shared DNA: A quick fun fact – we mentioned siblings share ~50% of their DNA. Why not exactly 50% every time? Because of how sexual reproduction works. Each parent gives you half of their chromosomes, but which half is random. So you and your sibling might get slightly different mixes of each parent’s genes, resulting in roughly (but not exactly) half-identical DNA. On average it’s 50%. Now here’s a kicker: pick any two unrelated humans on Earth, and their DNA will be about 99.9% identical. That remaining 0.1% contains all the variation responsible for differences in appearance, disease risk, etc. And out of that tiny 0.1%, the differences between, say, a San person and a Chinese person might be a bit greater than between two Chinese people or two San people (because their populations were separated for longer). But those differences are still minuscule. Every human alive is, at most, a 50th cousin of any other human. The San are our cousins, not some separate category of creature. (It’s incredible to think about – if aliens came to Earth, they’d laugh at how we fuss over skin color or eye shape when we’re all practically genetic twins).

- When DNA Testing Began & How Fast It Is Now: We touched on this, but to recap with clarity: Modern DNA testing began in the 1980s, with the first use of DNA in a police case around 1986. The field has exploded since then. Early tests (like DNA fingerprinting) compared a few markers and could tell if two samples matched or if someone was family. Today’s tests can scan your entire genome in one go. How long does a DNA test take now? Well, sequencing a human genome can be done in a day with cutting-edge machines, but analysis and processing add some time. If you spit in a tube for an ancestry company, you’ll wait 6-8 weeks mostly due to shipping, batch processing, and analyzing results. A hospital genetic test might get results in 1-2 weeks. A forensic test for crime might be rushed in days. And as one genomics company cheekily notes, you can get a dog’s DNA tested in under a month too (woof!). The trend is ever faster and cheaper – sequencing cost plummeted from $3 billion for the first genome to around $600 or less today. This speed is part of what enabled scientists to look at diverse groups like the San and include them in the global genomic conversation.

Alright, science hats off again, back to the narrative – because as awe-inspiring as the genetic findings are, they lit a fire of controversy that is still burning. This is where our story shifts from wonder to ethics, from “Yay, we found the oldest DNA!” to “Wait, did we handle this discovery right?”

The Newest Battle of Ethics, Consent, and Indigenous Rights

The year is 2010. The genome of four Namibian San men has just been published in the prestigious journal Nature. In the paper, the researchers describe the San as “Bushmen” and celebrate them as genomic gems. The global media picks it up, fascinated that the “Bushmen have the oldest DNA lineage.” Scientists pat themselves on the back for a groundbreaking study. It all sounds positive, so just imagine the researchers’ surprise when a formal complaint lands on Nature’s desk shortly after – an angry letter from a Namibian NGO representing indigenous peoples. The authors are accused of “absolute arrogance, ignorance, and cultural myopia.” Yikes. What went wrong?

From the perspective of many San leaders, this genome project felt like the latest in a long line of offenses. “We’ve been bombarded by researchers over the years,” said Hennie Swart of the South African San Institute. Scientists, journalists, filmmakers – all fascinated by the San – had frequently come into their communities, extracted information (or blood samples), and left, often without so much as a thank you or follow-up. In this case, though the geneticists did obtain consent from the four San men (they even filmed video of the men giving verbal consent through a translator), the broader San community leadership wasn’t consulted.

The San leaders questioned whether those elderly participants fully understood what the DNA study entailed – after all, giving truly informed consent in a foreign academic study is tricky when you’re not familiar with concepts like genome sequencing. Adding insult, the published article used the term “Bushmen,” a word that many San find derogatory (a relic of colonial times when they were often treated as sub-human). That’s why the NGO letter bristled with anger – to them, it felt like their people’s DNA was taken and showcased in a way that disrespected their culture and autonomy.

This incident started a new battle – not fought with bows or spears, but with voices, ethics codes, and demands for respect. At it’s core is the principle of indigenous data sovereignty. In simple terms: who owns and controls data (like DNA information) about indigenous peoples? Does it belong to the scientists who sequenced it? The universities that funded the research? Or the people whose blood carries that DNA? For the San, the answer was clear – it’s their DNA, their story, and they should have a say in how it’s used.

In March 2017, a remarkable thing happened. The San people took the initiative and released the San Code of Research Ethics – the first of its kind by any indigenous group in Africa. In a way, they turned their experience into a teachable moment for the world. The code basically says: Researchers, you’re welcome to study us – but you must do it on our terms, with respect. It’s a beautifully straightforward document that lays down guidelines such as:

- Community Approval: Scientists must submit their proposals to the San leadership councils for evaluation and approval before beginning research. No more sneaking in with government permits only; the community wants a seat at the table from day one.

- Informed Consent (for real): Researchers should ensure participants truly understand what the study is about, what will be done with their information, and what benefits or risks might come. Simply filming someone saying “yes” in a language they barely understand is not enough.

- Respect and Privacy: No taking photos of individuals without permission, no publishing identifiable images or personal details without consent. The San have dignity and deserve privacy, just like anyone.

- Fair Return of Benefits: If a study has some benefit (monetary or otherwise), share it with the community. This doesn’t just mean payouts – it can be opportunities like hiring local translators, giving skills training, or ensuring the community gets access to any medical insights that arise. In one famous case years earlier, San's knowledge of a desert plant led to the development of a weight-loss drug, and after negotiation, they secured a share of potential royalties as acknowledgment. The principle is: don’t just treat us as sample sources; make us partners.

- No Exploitation or Bribery: Researchers shouldn’t bribe people to participate or coerce them in any way. (One can imagine unscrupulous folks handing out shiny trinkets or cash to poor villagers for blood samples – the code explicitly says that’s not okay.)

- Right to Review: Perhaps the most controversial point – the code asks that researchers discuss their findings with the San community before publishing, to allow the community to flag any misunderstandings or sensitive information. This isn’t about censoring science; it’s about avoiding harm. For instance, if a genetic study accidentally revealed something private about a participant or said something that could be misinterpreted to the San’s detriment, the community would like a chance to clarify or respond. Some academics initially squirmed at this (“Scientific results shouldn’t be subject to non-scientist approval!” they argued). But others recognized it as an important gesture of respect – a checkpoint to ensure the research doesn’t stigmatize or misrepresent the people it’s about.

The San Code of Ethics was widely applauded as a step toward ethical, collaborative research.

It’s part of a broader movement often called “decolonizing science” – essentially, making sure that the people who were once just subjects of study become active participants or leaders in that process. Other indigenous groups around the world, like some First Nations in Canada or Aboriginal Australians, have developed similar ethics frameworks. The idea isn’t to hinder science; it’s to enrich it by building trust and ensuring studies are done with people, not on people. As geneticist Himla Soodyall put it, if those are the protocols the San expect, researchers should honor it – “that’s what social justice is all about”.

To the San, this battle is about much more than one DNA study. It touches on centuries of marginalization. From colonial times, San communities were pushed off their ancestral lands, sometimes hunted or enslaved, later forced into farming or menial labor. By the 20th century, they were often treated as second-class citizens in their own countries. Even in recent decades, San people in Botswana fought legal battles for the right to live in their traditional territories in the Central Kalahari Game Reserve, against government attempts to relocate them (allegedly for wildlife conservation but possibly due to diamond mining interests). Amid such struggles, being poked and prodded by curious researchers without respect feels like salt in the wound. The code of ethics was a way of reclaiming ownership – saying “This is our narrative. We are not mere specimens or ‘primitive relics’; we are living communities with rights and voices.”

One particularly poignant issue is the narrative around “the oldest DNA” itself. Yes, the science shows the San carry very ancient lineages. But some San have expressed discomfort with how that gets portrayed. They don’t want to be seen as “living fossils” in a zoo exhibit. They are modern humans, not time-traveling aliens at Area 51. The phrase “oldest race” can also unfortunately feed into racist tropes if misused – it has to be explained in the right context (meaning oldest ancestral lineage, not that any humans are less evolved than others, all current humans are equally evolved). So there’s a delicate balance in celebrating the San’s unique genetic heritage without stereotyping or dehumanizing them; a balance of scientific wonder with human respect.

Ancient Lessons for Modern Humanity

The story of the San people knits together ancient human history, cutting-edge genomics, and contemporary ethics. It’s part adventure story, part science lesson, part moral reflection. If you’ve read this far, you might be feeling that contagious curiosity that’s always encouraged– the feeling that you want to know more, dig deeper, ask big questions. Good! The San story leaves us with plenty of big questions and here are some:

- When we marvel at the San’s ancient DNA, are we doing so with a spirit of unity (recognizing them as our elders in a sense), or with a patronizing gaze that exoticizes them?

- As science advances and genome sequencing of different groups becomes commonplace, how do we ensure ethical practices? Will other marginalized communities be able to demand the same respect the San did?

- And here’s a question that might keep you up tonight: if the oldest DNA on Earth speaks of our common origin, will the newest battles over data, identity, and sovereignty pull us apart or bring us together?

In one sense, the San people’s story is deeply emotional. It has heart-wrenching chapters of loss and resilience – from being nearly wiped out by colonial violence to struggling in poverty on the fringes of modern society. But it also has inspiring chapters of hope and wisdom. Their humble way of life contains lessons of sustainability and connection to nature that the rest of us, in our high-tech bustle, desperately need. When a San tracker identifies dozens of animal prints on the ground after a quick glance, or finds water in a dried root in the desert, it shows of how humans are animals – clever ones, yes, but still part of the web of life. The San have never forgotten that and perhaps that’s why they survived for tens of thousands of years.

Harari’s Sapiens book ends by asking what will become of humanity – having grown into gods, will we know what we want next? Maybe the answer lies partly in looking back at those who never ceased living in harmony with the world as humans and animals. The San’s story invites a sense of wonder. It’s almost poetic justice that as we hurtle into an age of genomics and AI, an age obsessed with the new, we are drawn to the wisdom of one of the oldest cultures.

The San people often say, “We are all one” in their own language when talking about community. Genetic science literally backs that up: we are all one big family. The San people of Africa are not just an “African tribe over there”, they’re our very, very distant cousins who held onto the old family recipes (both culturally and genetically) that birthed us all.

As we close this journey through time and code, consider this powerful insight: The measure of progress is both in discovering the oldest DNA or the next medical breakthrough and in how we treat the people who give us those discoveries. The San have given the world an immense gift, the key to unlocking human origins. How we repay that gift – with respect, equity, and understanding – is up to us.

Will we listen to the voices of the San and others like them as we chart the future of science and humanity? The answer to that question may well determine whether the story of Homo sapiens continues as a triumphant story of human unity and wisdom, or a tragedy of missed connections. The San, with quiet resilience, are waiting for our answer.

References: Sources for facts and quotes include the Independent, Wikipedia on San genetics, the Smithsonian Magazine on the San Code of Ethics, and an Undark article on the consent controversy, among others, preserving the historical and scientific accuracy of this account.