Understanding the Sierra Leone Civil War

Sierra Leone in the late 1980s was a land gleaming with diamonds yet mired in desperate poverty. The economy had crumbled under decades of misrule. While foreign companies hauled away billions in diamonds, ordinary Sierra Leoneans saw none of the wealth. In fact, between 1937 and 1996 Sierra Leone exported nearly $15 billion worth of diamonds, but most of that profit left the country, enriching foreign firms like De Beers while locals remained impoverished. By the mid-1980s, about 80% of the population lived on less than $1 a day. Basic services collapsed – health funding was slashed and schools fell into disrepair under IMF-imposed austerity. The government’s structural adjustment reforms, meant to stabilize the economy, instead gutted it: tens of thousands of workers lost their jobs, and hospitals literally ran out of supplies. Inequality reached grotesque levels. Only 22% of rural villagers had access to clean water, compared to 83% in the capital. Yet roughly four out of five Sierra Leoneans lived in those underserved rural areas. It was a powder keg of poverty, unemployment, illiteracy, and resentment – circumstances that made Sierra Leone ripe for revolution.

Diamonds and Misery Fuel Outrage

The hardship was all the more infuriating because Sierra Leone was rich on paper. Besides diamonds, the country boasted abundant minerals (gold, bauxite, rutile) and fertile land. But corruption and neopatrimonial politics (a small elite hoarding power and resources) meant those riches never benefited the people.

For 24 years the authoritarian All People’s Congress (APC) regime under Siaka Stevens and Joseph Momoh siphoned off wealth for cronies and pals in Freetown, neglecting the countryside. By the 1970s Sierra Leone had effectively become a “shadow state” – government in name, but in reality a nexus of illicit mining deals and patronage networks feeding on public funds.

Foreign meddling compounded the misery. International lenders demanded budget cuts that diminished spending on education and healthcare. The national currency was devalued at the IMF’s behest, making Sierra Leone’s diamonds cheaper for export and further shrinking revenues. The result? An educated, employed life was out of reach for most. The average adult had roughly 3.6 years of schooling, and jobless youth drifted through city slums and villages with equal desperation. This was the devastated landscape into which a former military and camera man, Foday Sankoh, would step in and fire up a rebellion.

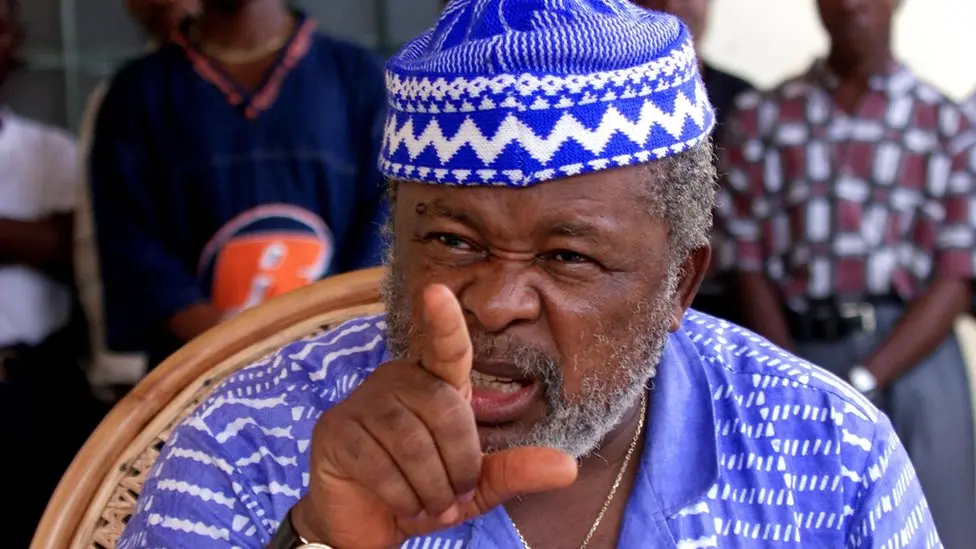

The Making of a Revolutionary

Foday Saybana Sankoh did not appear from a vacuum, no. He was an army corporal who had witnessed his country’s decline firsthand. In 1971, he was jailed for involvement in an attempted coup against the corrupt regime. That prison term hardened his resolve.

After release, Sankoh wandered the provinces as an itinerant photographer, coming face-to-face with the human toll of bad governance: hungry children, jobless young men, villages without schools. By the late 1980s, he and two kindred spirits – Rashid Mansaray and Abu Kanu – began quietly recruiting for an armed uprising to oust the APC government. The trio traveled to Muammar Gaddafi’s Libya, where they trained alongside other anti-colonial radicals. Sankoh regularly invoked pan-African revolutionary ideas, and indeed he first met Liberian rebel leader Charles Taylor in Gaddafi’s guerrilla camps.

Driven by visions of African unity and socialist liberation, Sankoh returned with a mission to reset and rebuild Sierra Leone’s future by toppling the old order. He framed the coming struggle in grand historical terms, casting himself and his followers as heirs to past freedom fighters. In his rhetoric, the corrupt elites in Freetown were “vampires” sucking the people dry, and it was time for ordinary Sierra Leoneans – the farmers, the miners, the neglected rural tribes – to seize back their country. This intoxicating message of righteous revolution began to spread in whispers and secret meetings across the border in Liberia, where Sankoh struck a disastrous alliance.

The R.U.F Invasion

On March 23, 1991, Foday Sankoh made his move. With the backing of Charles Taylor’s forces from Liberia, Sankoh and a small band of guerrillas crossed into Sierra Leone’s eastern Kailahun District. They called themselves the Revolutionary United Front (RUF). Their stated aim was as bold as it was enticing: end the APC’s 24-year stranglehold on power and rescue Sierra Leone from tyranny and kleptocracy. In those early days, Sankoh presented the RUF as liberators coming to finish what Sierra Leone’s independence had failed to deliver – true self-governance and social justice for the masses.

The initial rebel contingent was tiny (fewer than 200 fighters) and many were actually Liberian or Burkinabé, lent by Taylor. But the RUF quickly tapped into local grievances. As villages fell to the rebels, some marginalized youths and disaffected villagers welcomed them, or at least sympathized with their anti-government slogans. Sankoh’s fighters struck at border towns and the diamond-rich interior, exposing how feeble and demoralized the national army had become.

The once-invincible APC regime began to wobble. Ironically, within a year a group of young Sierra Leonean army officers staged their own coup in Freetown (in April 1992) – inspired in part by the same disgust at corruption that Sankoh had been voicing. For a moment, it seemed the rebels’ rallying cry against misrule had ushered in the change they sought, if not exactly in the way they envisioned. But Sankoh was not about to lay down arms and trust the military junta. The RUF dug in for a prolonged fight, determined to remake the country on their terms.

Voice of the Revolution - Sankoh’s Radio Propaganda

What really set Foday Sankoh apart was his skill as a propagandist. Armed with an AK-47 in one hand and a microphone in the other, he turned radio broadcasts into a revolutionary theater.

In April 1991, just weeks after launching the insurgency, Sankoh’s voice carried across the airwaves of the BBC World Service – the same station many Sierra Leoneans relied on for uncensored news. Speaking from the bush, he coolly declared his objective was “an end to the one-party system” under President Momoh. He assured listeners that the RUF fought not to install Sankoh as a new strongman, but to free the country from oppression. This was classic Sankoh because on radio he had struck a tone of principled insurgency, even as RUF attacks grew brutal on the ground.

Throughout the early 1990s, Sankoh continued to beam out messages via clandestine transmitters and cassette tapes smuggled to sympathetic radio operators.

In the jungle camps, he and his confidants (Mansaray and Kanu among them) would huddle around a transmitter, recording fiery monologues to rally their fighters and entice new recruits. These audio messages – sometimes aired on occupied local stations or passed hand-to-hand on tape – emphasized the RUF’s revolutionary rhetoric. Sankoh hammered at themes of equality, blasting the “rotten system” in Freetown that left youth jobless and villages forgotten. He promised free education, jobs for the jobless, and a fair share of the diamond wealth once the old regime was swept away. Listeners as far away as Freetown heard his booming voice crackle over the radio, denouncing “tribalism and corruption” and invoking heroes like Nkrumah and Lumumba. The medium was the message, by using radio – the “bush telephone” of West Africa – Sankoh gave his revolution an aura of inevitability, as if the very air carried the winds of an impending change.

Even when he was in hiding or later in prison, Sankoh found ways to broadcast instructions. (During a 1997 junta, one of his orders was recorded on tape and played over the airwaves to his followers.) The radio became his pulpit, and every broadcast further mythologized his crusade in the minds of supporters.

Revolutionary Intentions and Imagery

From the outset, Foday Sankoh did not cast himself as a power-hungry warlord, he was the next visionary liberator. His initial intentions – at least in his own pronouncements – were very idealistic. He spoke of a “New Sierra Leone”, a country that would finally belong to its people and not to foreign interests or a thieving elite. The RUF’s 1995 manifesto, Footpaths to Democracy, channeled Sankoh’s radio messaging. It railed against the “injustice and inequality” of the old order and sketched an almost utopian plan for grass-roots democracy and equitable development.

Sankoh’s ideology, as it was articulated, blended raging anti-colonial Marxism with populist grievances. He regularly invoked the birthright of Pan-African revolution – the idea that Sierra Leone’s struggle was part of a larger fight to free Africa from neocolonial shackles. In his broadcasts he would reference the plight of miners in Kono, the farmers in the provinces, the slum dwellers of Freetown, painting vivid scenes of their suffering under APC rule. Then, with dramatic flair, he offered the RUF as the people’s army that would right these wrongs.

His speeches were full of rhetorical questions – “Are you not tired of being poor in a rich land?” – and simple slogans in Krio so that even the uneducated could grasp the cause. He was, in effect, waging a war of images and ideas: the starving child, the out-of-work youth, the village without water – all contrasted against the glitter of diamonds on a foreign tycoon’s desk. This contrast fueled the RUF’s early recruitment. Many who initially joined or supported Sankoh did so believing in his promises to deliver social justice. Anecdotes from early recruits recall Sankoh telling them around campfires that once victory was achieved, every child would go to school and no region would be left without roads or clinics. Such vows resonated powerfully in a country where, as one statistic highlighted, 80% of rural residents had no access to clean water while city elites lived comfortably. Sankoh masterfully turned this stark reality into a rallying cry for revolutionary change.

A Charismatic but Ominous Ascent

By the mid-1990s, Foday Sankoh had become a figure of both hope and fear in Sierra Leone. To his followers and many downtrodden citizens, he was almost a Robin Hood figure – the ex-soldier from the provinces who dared to stand up to entrenched power. He was the man who had braved imprisonment and exile to return with a gun in hand, saying “No more!” to poverty and indignity. Sankoh’s rise was buoyed by genuine grievances that he astutely amplified. The economic despair, the exploitation of the diamond trade, the meddling of foreign powers, and the years of authoritarian neglect all coalesced into a powerful narrative that Sankoh rode to prominence. In those early years, his energy and confidence were infectious. Villagers would later recall how RUF fighters entered their towns blaring Sankoh’s speeches from battery-powered radios, as if to announce that the revolution had arrived. Sankoh himself, with his trademark beret and fiery oratory, seemed to embody a new era on the horizon.

It is important to remember that at this point – the rise of Foday Sankoh – the final outcome of Sierra Leone’s civil war was far from certain. History would later record the brutality and sorrow that the RUF brought, but in the beginning, the focus was on why they fought. Sankoh’s initial agenda spoke to righting the wrongs that ordinary Sierra Leoneans had endured for decades. He harnessed their anger and their yearning for dignity. As an observer noted, the war “rapidly acquired an indigenous Sierra Leonean character,” born from local support created by the very injustices the rebels decried. In those first chapters of the conflict, Sankoh’s revolution was fueled as much by ideas and popular frustration as by guns.

In sum, Foday Sankoh’s ascent from disgruntled ex-corporal to rebel leader was produced in the crucible of Sierra Leone’s economic collapse and social despair. His charisma, radical ideology, and deft use of radio propaganda Ignited the powder keg of a nation ready to blow. He promised liberation, self-determination, and an end to the exploitation of the poor. And for a time, many believed him. Sankoh’s rise to power tells us a story of how hope and fury converged in a land of great wealth and great suffering – a tale that unfolded with the energy of a revolution and the cadence of a radio broadcast cutting through the silence of a long-dark night.