What Drove The German People To Support The Vile Nazi Regime?

World War I drew to its cataclysmic close following a fleeting, 22-day German offensive, which met its demise at the Second Battle of the Marne, deep in the heart of France. As the guns fell silent, a new conflict was unwittingly being woven by the Allies with the penning of the Treaty of Versailles in June 1919. This document, more a harbinger than a peace accord, entangled Germany in a web of economic, political, and social quandaries, casting a shadow over the nation for more than a decade. Little did the Allies realize, in their pursuit of peace, they were not nurturing a butterfly in a chrysalis but rather fostering a wasp, poised to awaken with a sting that would once again plunge the world into turmoil. This was a chrysalis of revenge and retribution, from which a new terror would emerge, shaking the very foundations of global order.

In the years between 1919 and 1933, the German populace found themselves adrift in the turbulent seas of the Weimar Republic's hesitant governance. This era, marked by its sluggish pace and indecisive actions, left the people yearning for a beacon of hope, a path leading out of the darkness. It was in this landscape of desperation and disarray that the insidious promises of the Nazi regime began to resonate with an unsettling allure. The Nazis, cloaked in the guise of salvation and strength, extended a hand to the powerless, offering a false dawn. Little did the people know, this was not a lifeline, but a pact with a malevolence that would cast a long shadow over history, as the nation teetered on the brink of an abyss, unknowingly poised to plunge into an era of unprecedented horror.

First Came Humiliation

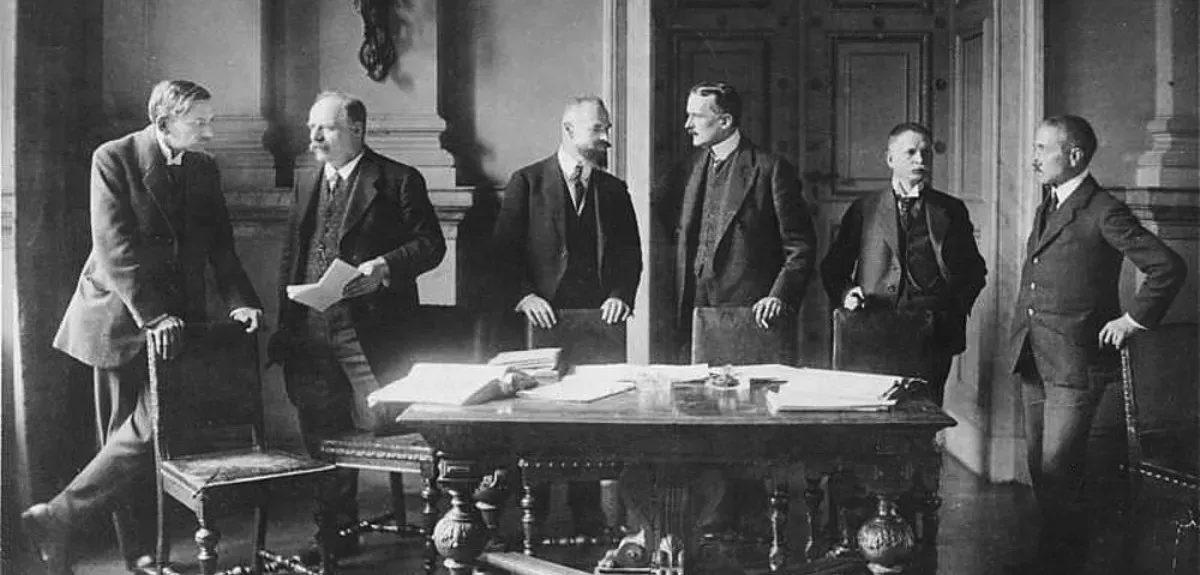

In the wake of World War I, the Allied powers, driven by a desire for retribution, set their sights on making Germany atone for the devastation wrought across Europe. January 1919 witnessed the birth of the League of Nations, a new stage upon which the drama of post-war diplomacy would unfold. Within this arena, the victorious nations—Italy, France, Britain, and the United States—jostled to assert their territorial claims. Yet, the crux of judgment fell upon the shoulders of the 'Big Three.' French delegate Georges Clemenceau harbored a fierce resolve to hamstring Germany to the point of impotence, ensuring it could never again rise as a European menace. Across the Channel, British Prime Minister David Lloyd George sought to defang Germany's military might. Meanwhile, U.S. President Woodrow Wilson, a visionary, yearned to erect safeguards against the specter of future global conflicts. Together, these three architects of peace crafted a consensus fraught with implications.

During the somber aftermath of the Great War, Germany, bruised and battered, stood in the shadow of a looming dread: the specter of war reparations. The burden of defeat weighed heavily upon the nation's shoulders. It was in this climate of fear and uncertainty that Friedrich Ebert, Germany's first president in the post-war era from 1919 to 1925, faced a momentous decision. The pivotal turning point arrived with the delivery of a delegation letter in May 1919, bearing the harsh and humiliating terms of the treaty.

Ebert, upon perusing the document, was confronted with terms that seemed more like a victor's vindictive decree than a fair settlement. His initial instinct was one of outright rejection, a stand against what he perceived as an affront to his nation's dignity. However, the harsh reality soon dawned upon him. These were not mere proposals open to negotiation but mandatory dictates. With a heavy heart and a sense of resignation, Ebert realized that defiance was not an option. The terms were not just written on paper but were carved into the fate of Germany. Reluctantly, with the weight of a defeated nation on his shoulders, he signed the treaty, sealing a course of history that would have far-reaching and lasting consequences.

Second Came The Treaty of Versailles

The League of Nations, in its post-war orchestration of the map of Europe, made declarations that cut into the very flesh of Germany. It was decreed that Poland would rise anew as a sovereign state, cleaving from Germany lands that the German people held in their hearts as an intrinsic part of their heritage. Alsace-Lorraine, nestled along the Rhine river, a region soaked in the blood and history of Franco-German conflict, was to be returned to French hands. Moreover, Germany was to cede 13% of its territory, including the hallowed and industrious Rhineland—its verdant fields and strategic position along France and Belgium now placed under the watchful eyes of Allied authority, a sentinel presence slated to last for three decades.

The edicts did not end at land alone. Germany was commanded to dismantle the pillars of its military might, with its army to be pruned to a mere 100,000 men. The remnants of its once-proud naval fleet were destined for British possession. Coal and steel, muscle of the nation's industrial power, were to be mined and forged only to be handed over to France and Belgium in vast quantities. Adding to the weight of these demands, the Treaty imposed a staggering financial yoke upon the German people: 132 billion gold marks in reparations, an astronomical sum when compared to the currency of the year 2024—just over a half-trillion U.S. dollars.

The proclamation to the citizens of the German Reich on June 24, 1919, was a missive tinged with a somber tone. It spoke of daunting labor and the need for meticulous coordination, for the path to recovery was steep, strewn with the rubble of social and economic ruin wrought by the war and the onerous terms of a peace treaty that was more a straitjacket than a salve. The notice was clear: the road to restoration, to return to the glory and stability of yesteryear, would be an uphill battle against the harsh terrain of the conditions set forth by a world that seemed to demand the impossible.

For the German people, the feeling of isolation was profound; they stood solitary, their plight a stark tableau against the backdrop of international scorn. Their struggle for survival, for some semblance of sustenance, was theirs to bear alone. The Treaty had not just stripped them of territory and power but had robbed them of their pride and place in the world, leaving a once-proud nation grappling with a new identity as it sought to navigate the churning waters of a reality it never imagined it would have to endure.

Third Came Inflation

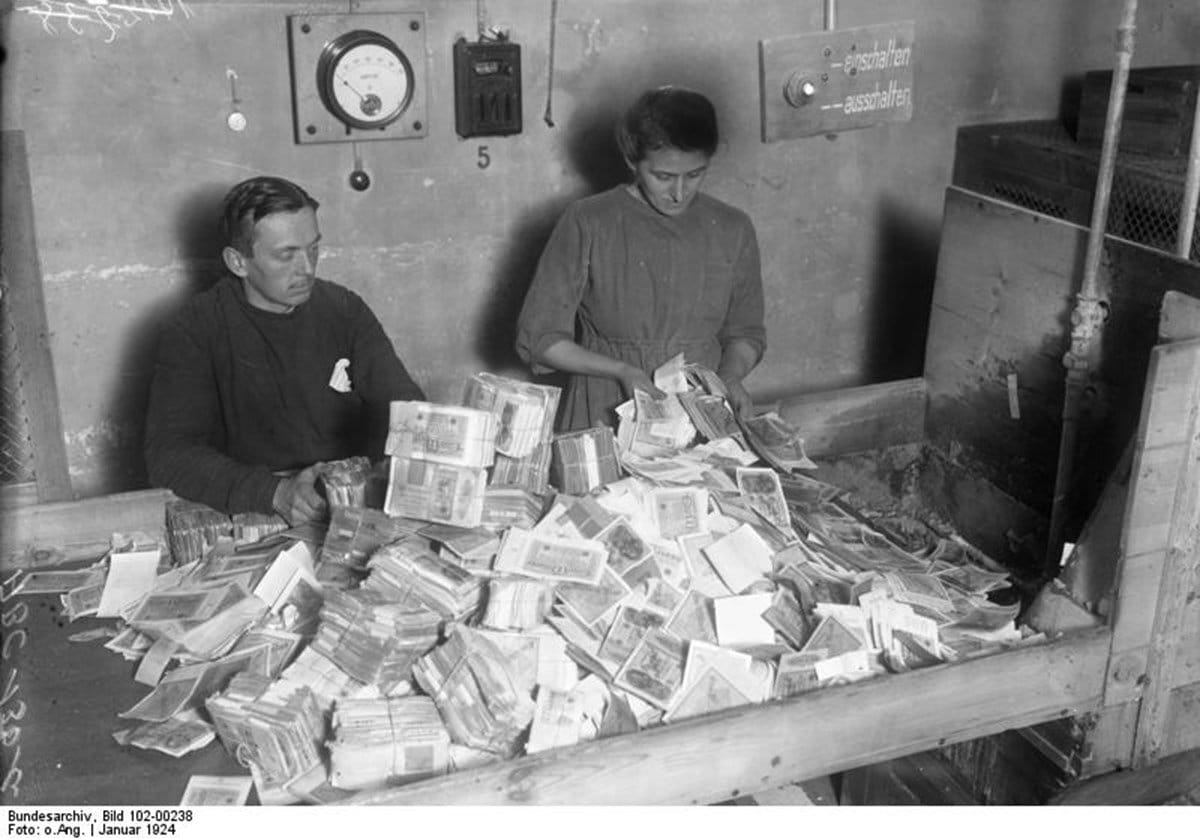

As Germany labored under the staggering weight of reparations, the economic foundations began to tremble. The Versailles Treaty, signed in 1919, was not merely a document of surrender but a prelude to financial ruin. The Papiermark, once the sturdy currency of a proud nation, began to crumble in value as the post-war years wore on. The specter of inflation haunted the marketplace, as the cost of everyday commodities soared to unfathomable heights, far eclipsing the dire scarcities faced during the wartime years.

The spiraling crisis reached a fever pitch on March 13, 1920, when the capital bore witness to the anguish of 12 million workers amassed in Berlin. Their voices rose in unison, a colossal wave of protest against a government they perceived as lethargic and disconnected from the dire straits of its people. The Weimar Republic, jolted by the resounding clamor, scrambled to forge a more compassionate approach to the allocation and affordability of sustenance. While a select few indulged in the opulence of more extravagant fare, the harsh reality for the many was a grim struggle to procure the most basic of needs: bread, potatoes, butter. This struggle, borne of necessity and despair, kindled the flames of rebellion, paving the way for a coup that would echo through the annals of history, a stark reminder of the desperation that can grip a society pushed to the brink.

Certainly, I will merge the explanations to offer a comprehensive narrative that contextualizes the hyperinflation in post-World War I Germany with today's monetary values for a clearer understanding.

In the immediate aftermath of the Treaty of Versailles, Germany found itself grappling with an economic maelstrom. The national currency, the Papiermark, once stable, began to succumb to rampant inflation soon after the country's acquiescence to the Treaty's terms in 1919. To illustrate the severity of this inflation with modern comparisons: imagine, in 1918, purchasing a loaf of bread for what would be equivalent to $1 today—a common enough expenditure. Yet, by 1922, the same loaf would cost the equivalent of an exorbitant $200, a price that would render daily sustenance a luxury for many.

The fiscal turmoil reached its peak in 1923 when the price of bread inflated to the mind-boggling equivalent of millions of dollars today. The surreal escalation rendered the currency nearly worthless, creating a scenario where bartering with valuables became a norm, reminiscent of a bygone era of trade.

Amidst this backdrop of financial chaos, even Albert Einstein, whose theories on the cosmos were gaining acclaim, was not immune to the economic plight that befell his nation. His ascent to fame was paralleled by a struggle against the very real and personal impact of his country's spiraling currency devaluation.

The Weimar Republic, in a desperate attempt to stem the tide of economic despair, halted reparation demands in 1923, striving to maintain the affordability of basic commodities for its citizens. This act can be likened to a modern government stepping in to subsidize essential goods in a crisis. However, the Allies' response was swift and punitive. French and Belgian forces, led by Raymond Poincaré, invaded the industrial regions of the Rhineland and Ruhr. This military incursion, executed in 1923, was not only a strategic move to claim the unpaid coal and steel but also served as a stark political statement, enforcing the harsh terms of the Treaty.

The occupation of these crucial industrial areas by foreign forces was a tangible and demoralizing consequence for Germany, akin to a foreign power today seizing control of vital infrastructure and resources. It was a move that underlined the extent of Germany's subjugation and the relentless enforcement of the Allied powers' will upon a nation already reeling from economic and social upheaval.

Fourth Came Occupation

The occupation of the Rhineland by France and Belgium marked a new chapter in Germany's post-war saga—an era characterized by foreign boots on German soil. The wartime allies of France and Belgium observed with vested interest, yet the two nations pressed forward with their agenda. They severed the lifeline of communication between the Rhineland and the rest of Germany to the east, effectively isolating the region. In a bold assertion of control, a military-led administration was established, dictating the governance of the Rhineland with an iron fist.

In an act that only compounded the economic strife of the Ruhr's residents, the occupying forces imposed additional taxes. This move showed a flagrant disregard for the crippling hyperinflation that rendered the Papiermark virtually worthless. It was a clear message: the occupiers valued their own reparations over the economic viability of the region. The Ruhr, an area already suffering from the financial collapse of the currency, was now doubly burdened, taxed in a currency that was spiraling into oblivion. The French and Belgian authorities were indifferent to the inflationary crisis, focused solely on extracting their due, blind to the worsening plight of the German people under their control.

Amidst the French and Belgian occupation, the rural expanses of the Rhineland, once the breadbasket of Germany, became a region cut off from its hinterland. Farmers, who played a critical role in feeding the nation, found themselves ensnared in an economic quagmire. Bereft of communication with inland markets, they were compelled to blindly set the price of their produce, using the costs from the nearby Alsace-Lorraine in Saarland, Eastern France, as their only barometer. This was a haphazard method, dictated more by guesswork than the economic realities within Germany, and it was deeply flawed.

France's strategic maneuver to dismantle Germany's economic synergy was bearing fruit. The disconnect sowed by the occupation created a maelstrom of confusion and disarray in food distribution and social expenditure. As the economic threads that once wove the country together began to unravel, the fabric of German society was torn, leading to a discord that set consumer against producer. This rift was not merely economic—it was a division that sowed the seeds of civil unrest.

Prices, demand, and wages began to climb in a discordant symphony, escalating tensions within the populace. The black market thrived in these conditions, feeding off the chaos and the desperation of a people struggling to find their footing in a landscape where the traditional rules of commerce and communication had been upended. Violence erupted as the very sinews that held society together were strained to breaking. In this atmosphere of volatility and fear, the black marketeers operated with impunity, a shadow economy growing ever stronger amidst the turmoil.

Fifth Came Disappointment

The Weimar Republic, in its quest to alleviate the growing chasm between food production and distribution, found itself mired in debate and ineffective solutions. Attempts to streamline the process of getting farmed goods to the people floundered as they struggled to establish coherent trade with the cultivators. The shifting of responsibilities from one food ministry to another did little to solve the core issues. Efforts to fix quantities and prices for the Rhine region were met with discordance, exacerbating the disparities in currency values across different parts of Germany. This lack of harmony in the economic policies further eroded the already depreciating Papiermark, which continued to lose value as it poured off the printing presses.

In a bid to restore some semblance of financial stability, the Weimar Republic implemented a plan that was, at best, a stopgap measure. Workers began to be paid more frequently—thrice a week—in an effort to bolster public confidence. This was intended to assure citizens that the price they paid for essentials like potatoes would hold steady, at least for a day. However, this policy fell short of restoring lasting financial order. In a desperate scramble to preserve purchasing power, it became a common sight to see consorts of women waiting anxiously outside of coal and coke factories. As their men emerged with fresh earnings, the money was quickly handed over, and a frenetic rush

to the nearest stores ensued, with the women vying to buy groceries before the next inevitable price hike took effect.

This tumultuous situation underscored a profound disillusionment with the Weimar Republic's ability to lead the nation out of its crisis. The government's perceived inaction or inadequate action led many to conclude that the proverbial light at the end of the tunnel was nothing more than an illusion, a mirage of hope in a landscape bereft of solutions.

The conditions were ripe for the black market to thrive and for dissent to coalesce into organized rebellion, particularly in the Rhineland and the Ruhr. The residents, spurred by necessity, defied the French, took food distribution into their own hands, and, in some instances, even created alternative currencies—actions that, while innovative, only served to further destabilize the already fragile economy.

As the Weimar Republic's strategies crumbled, the few years of interwar peace were revealed to be a veneer, masking the deepening social and economic scars that would soon become all too apparent to the German public. The peace had been bought at a high price—a price that the nation was not yet fully aware it would have to pay.

Sixth Came Depression

In the mid-1920s, as the economic situation in Germany teetered on the brink of collapse, a shift in international sentiment began to take hold. The United States and Britain, moving away from the punitive stance that had defined the Treaty of Versailles, began to question the wisdom of holding Germany solely responsible for the First World War. This was in stark contrast to France's unyielding position. Out of this changing atmosphere, the Allies formulated the Dawes Plan in 1924, spearheaded by Charles G. Dawes, an American banker and politician. This plan aimed to ease the reparations burden on Germany by structuring payments according to the nation's ability to pay, a move that was seen as a more humane approach to the economic crisis engulfing Europe.

The Dawes Plan appeared as a beacon of hope for Germany, promising not just to stabilize the beleaguered nation's economy but also to restore a semblance of order. The oppressive terms of the original treaty had plunged Germany into a spiral of economic and social turmoil, but now, with the influx of foreign loans, particularly from the financial powerhouses on Wall Street, there seemed to be a path to recovery. The Weimar Republic experienced a significant easing of domestic strife as these funds flowed into the country.

However, this reliance on foreign capital proved to be a double-edged sword. When the Great Depression struck in October 1929, it sent shockwaves through the global economy, and Germany found itself under immense pressure to repay the loans it had received. The country's financial structure was inextricably linked to the international banking system, and as the Depression deepened, that system began to unravel.

Germany, amidst this economic catastrophe, watched as the financial institutions across Europe began to collapse. The contagion started in Austria, the seat of the largest bank in the European Union at the time, and rapidly spread to Vienna, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and beyond. Like a row of dominoes, once one bank fell, it precipitated the fall of others in rapid succession. The Depression was not just an economic downturn; for Germany, it was an outright financial calamity, one that would test the resilience of the Weimar Republic and its people to the utmost.

The Great Depression marked an era of unprecedented financial hardship and uncertainty, and Germany was at the epicenter of this global crisis. The banks, overwhelmed by the spiraling economic situation, could no longer meet the needs of their clients. Trust in these institutions eroded rapidly as people became increasingly alarmed by the worsening global recession. The panic reached a climax when the Reichsbank, Germany's largest bank and the linchpin of its financial system, shut its doors. This closure sent a ripple effect throughout the nation, leading other banks to meet the same fate.

The fallout from these closures was catastrophic. Unemployment soared to staggering heights as millions of Germans found themselves without work. For some, wage reductions forced them to abandon their jobs, while many others faced layoffs as businesses struggled to stay afloat in the floundering economy. The populace was engulfed by a virulent wave of depression, not just an economic one but a profound psychological despair that permeated the majority of households.

Yet, amidst the widespread destitution, there were those who found opportunity in the chaos. Astute businesses and landowners exploited the deflating currency, taking on loans and repaying debts at a fraction of their original value. This financial maneuvering allowed a select few to maintain, or even enhance, their wealth and lifestyle, even as the rest of the country struggled.

For the common people, the desperation was palpable. They yearned for a return to the days before the Treaty of Versailles, before the reparations, the economic collapse, and the social upheaval that followed. They sought a path back to stability and prosperity, a way to restore their shattered faith in Germany. The nation was ripe for change, for someone or something to rekindle the pride and hope that had been lost in the aftermath of war and economic disaster.

Last Came An Indoctrinated Nation

The final chapter of the Weimar Republic's troubled history was marked by widespread disenchantment and the rapid rise of extremist ideologies. The years of hyperinflation and the ensuing Depression had radically transformed daily life in Germany. Amidst the economic turmoil, a subset of society—certain business owners and landowners—managed to not only survive but thrive, exacerbating class tensions and fueling the rise of socialist sentiment among the beleaguered middle and lower classes. This growing divide contributed to the disintegration of support for the Weimar Republic, which was widely disparaged and deemed responsible for Germany's sustained humiliation and suffering at the hands of the victorious Allied powers.

The National Socialist Workers' Party, known as the NSDAP or Nazi Party, gained momentum by promising equality and the vision of a united Europe under a single ruler. Their message resonated with a populace desperate for change. In the 1928 elections, the NSDAP's relatively meager vote share began to climb dramatically. By the 1930 elections, their support had surged to over 6 million votes, signaling a profound shift in the political landscape and the unsettling reality of a population increasingly swayed by Nazi propaganda.

Theodore Heuss, a Reichstag official, chronicled the declining influence of the Reichstag and the alarming ascent of anti-Semitic sentiment, stoked by the National Socialists. Public disruptions by the S.A., the Nazi Party's paramilitary organization, and unruly youth targeting politicians and police with firecrackers were symptomatic of the growing unrest.

By 1933, reports from Professor Theodore Abel of Columbia University, based on interviews with a cross-section of German society, revealed a disturbing alignment with anti-Semitic and Aryan supremacist ideologies. The NSDAP's rise to power seemed inevitable as more and more citizens, from bank clerks to teachers, expressed support for granting the Party absolute control.

Racial tensions and anti-government protests spiraled, culminating in the Nazi Party supplanting the Weimar Republic by June 1933. With Hitler as Chancellor, his regime deployed the Gestapo to suppress dissent, although many Germans, disillusioned and desperate, willingly supported the Nazi cause, viewing Hitler as a savior who promised to restore their nation to greatness.

The economic hardship had eroded the relationship between tenants and landowners, with exorbitant rents further impoverishing the already struggling lower classes. The Nazi Party's promises of employment, housing, and renewed national pride appeared as a tangible solution to the pervasive despair.

While initial resistance to Nazism was not insignificant, the continued struggle of daily life led many to reconsider. Hitler's appeal transcended class barriers, garnering attention from the industrial elite to the common worker. At a pivotal meeting with the Industrieklub in January 1932, Hitler secured financial backing from influential industrialists, convincing them of his vision to restore Germany's prominence on the world stage.

The Nazi grip on media further entrenched their influence. The press, radio, newsreels, films, and educational content all became conduits for National Socialist propaganda, amplifying anti-Semitic sentiment, which, while not new to German society, was propelled to new heights under the Nazis. The seeds of this bigotry had been present long before, with anti-Semitic remarks traced back to currency scribbles in 1923, but by 1933, the Nazis had orchestrated a pervasive campaign of segregation and discrimination rooted in twisted interpretations of Darwinism and the writings of Martin Luther.

The true intentions of the Nazis, however, extended far beyond their public facade of unity and peace. General Erich Ludendorff's publication "The Total War" in 1935 hinted at the underlying militant ambitions of the Nazi regime. Meanwhile, plans for a sweeping militarization and a path to war were being laid as early as 1925, ominously detailed in Hitler's manifesto, "Mein Kampf." This period marked the calculated preparation for a conflict of unprecedented scale, as the Nazis sought absolute dominion not only within Germany but across the European continent.